Henning van Aswegen

The article is an extract from Spioenmeesters, published by Kraal Publishers, Pretoria, 2021. Spioenmeesters is available on Amazon.com:

Abstract: Operation Vula, insurrection, South African political crossroads, Groote Schuur Minute, Oliver Tambo, Joe Slovo, Tim Jenkins,

OPERASIE VULA – A Deadly Miscalculation

History repeats itself in strange ways, especially in the world of intelligence where white, black and grey propaganda, deception, deceit and false flag operations are the staple food of every intelligence service in the world. A covert espionage operation is not much of a success if your spies are compromised, arrested, prosecuted and sentenced, or your vaunted intelligence operation is compromised before it begins.

F.W. de Klerk and Nelson Mandela shaking hands at the conclusion of negotiations which resulted in the signing of the Groote Schuur Minute on 4 May 1990

In the late 1980s, the South African government faced harsh political choices and decisions – time was simply running out for the white minority rule in the country. South Africa’s racial policies was a fertile breeding ground for increasing domestic pressure and unrest, as well as extensive foreign economic sanctions that had crippling implications for South Africa and its people. Negotiations that would lead to a black majority government were the only option and way out to prevent a civil war in South Africa. The revelation of an underground ANC conspiracy under the pseudonym of a “Presidents Council (PC),” secretly organized to overthrow the South African government by force, made the already shaky political circumstances that prevailed at that stage even more volatile and unpredictable.1 This conspiracy, the ANC-SACP’s Operation Vula, 2 was exposed by South Africa’s security forces during the Codesa negotiation process between the National Party (NP) government and opposition groups. Vula was exposed as a semi-secret subversive effort of an extremist group of ANC-SACP members, most of them members of the Politico-Military Council (PMC) and the South African Communist Party (SACP) Central Committee.

Former president F.W. de Klerk’s landmark speech on 2 February 1990, during which the ANC and other restricted organisations were unbanned, was still fresh in minds of South Africans when news of the Vula plot appeared in the media. Nelson Mandela’s release followed a few days later, on 11 February and the negotiation process between the government and opposition began, at first informally and later formally at Groote Schuur and Codesa in Kempton Park. On 4 May, the Groote Schuur Minute, in which the government and the ANC committed themselves to peaceful negotiations, was signed. The talks at Groote Schuur were the first formal negotiations between the two parties and paved the way for bilateral talks that followed. Revelations about Operation Vula almost derailed these negotiations because it showed bad faith in the negotiation process. The operation was exposed, key role players were arrested and mistrust around the Codesa negotiating table increased.

The origin of Operation Vula

The origins of Operation Vula can be traced to a decision made by the SACP during its sixth congress in 1984 in Moscow, where the ANC-PMC was instructed to implement political decisions by the NEC of the ANC-SACP by way of the establishment of underground military structures within South Africa’s borders.3

Permission to implement the operation was granted two years later, in 1986, by means of a secret resolution of the ANC’s National Executive Committee ( NEC).4 The ANC-SACP’s leaders were cognisant of the Vula plot from Day One, as it was the brainchild of ANC president, Oliver Tambo and the SAC leader, Joe Slovo, who instructed Mac Maharaj, Siphiwe Nyanda (Ghebuza) and Ronnie Kasrils to establish and organize an underground network in South Africa with the objective of creating a “People’s Army.”5 This People’s Army would ostensibly be trained and provide with arms and ammunition to generate and participate in a “People’s Revolt.” Other key figures were Tim Jenkin, Ronnie Press, Janet Love, Jacob Zuma,6 Archie Abrahams, Billy Nair7 and Pravin Gordhan. In addition to establishing secret political and military command structures within the borders of the country, Vula was to establish shelters (safe houses) and weapons depots for their ”People’s Army” for the purpose of overthrowing the government by force.8 Tambo and Slovo wanted to establish senior ANC-SACP members within South Africa so that an experienced leadership could make operational decisions at grassroots level, without first having to consult the ANC-SACP leadership in Lusaka.9 Although plans for and the implementation of Operation Vula had already begun before the official negotiations between the government and the ANC-SACP and other parties, its implementation was not stopped when the negotiation process began with the unbanning of the ANC, SACP and PAC on 2 February 1990. According to a description of the history of the operation by the Constitutional Hill Trust, the ANC leaders discussed the continuation of Operation Vula after the negotiation process with the government was launched, deciding that it should continue, as an “insurance policy” in case talks failed. Oliver Tambo was concerned that the ANC should not allow negotiations to result in the movement being stripped of “our weapons of struggle.” Sanctions, the guerrilla force, and Operation Vula would remain until it was clear that the negotiation process was irreversible.10

Operation Vula was a crude attempt by a radical group in the ANC-SACP to overthrow the government through a terrorist campaign and acts of sabotage, the smuggling and storage of weapons and the establishment of an alternative political-military command structure. After negotiations began, it was, as it were, a plan B that had to be implemented if the negotiations were to fail.11

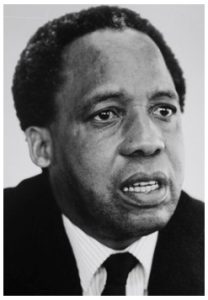

Former ANC president, O.R. Tambo (lefts) and SACP Secretary General Joe Slovo initiated and managed Operation Vula in 1985, the same year a friendly foreigh liaison service provided a-grade operational intelligence information obrained from British Telecom telephone lines.

Vula and Mayibuye

Operation Vula is reminiscent of the failed Operation Mayibuye (1961-1963), a similar attempt by ANC- SACP leaders to subvert state authority in South Africa through violence, sabotage and revolution. General Hendrik van den Bergh, former head of the Bureau for State Security (BFSS), writes in his book ‘No Boats in the Harbour’ that by electing and opting for the moral choice of violence, the ANC-SACP opened the way for the South African government to respond with violence.[1]

The implementation of Mayibuye, as with Vula, was hampered when the plan was eventually exposed, leading to the compromise, arrest and incarceration of all the protagonists. In the case of Operation Mayibuye, the leadership responsible for the operation was arrested on 11 July 1963 on the farm Liliesleaf in Rivonia and later prosecuted. The South African Police (SAP), led by lt. W.P.J. van Wyk, carried out a raid on Liliesleaf and arrested the supreme command structure of the ANC’s armed wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), including Govan Mbeki, Walter Sisulu, Ahmed Kathrada, Lionel Bernstein, Bob Hepple, Arthur Goldreich, Raymond Mhlaba and Denis Goldberg.12

Vula within the political context of the 1980s

As an intelligence operation, Operation Vula – and its aims – must be evaluated in the political context of the late 1980s. Mass action, under the auspices of the United Democratic Front (UDF), was the order of the day and militant revolutionaries within the ANC-SACP feared that this mass internal mobilization could lead to a change of government.13 The UDF’s popularity amongst a large number of South Africans caught the ANC-SACP off guard and they were eager to retain their leadership role in the liberation struggle. It was a time of sporadic state of emergencies, lockdowns and restrictions on both public discourse and the publications media. De Klerk’s predecessor, P.W. Botha, repeatedly warned about a total onslaught against South Africa.[2] In addition, public violence and sporadic bomb blasts occurred in several townships. By September 1989, the National Intelligence Service (NIS) was holding clandestine and top-secret talks with the ANC in Switzerland, prequal to the later Codesa negotiations.14

SACP, ANC and MK member Chris Hani

Militants within the ANC, concentrated in the ANC’s Department of Intelligence and Security (DIS), wanted to bring about regime change through violent action, not through mass action.15 This group included the MK’s head of staff, Chris Hani, the hardline communist Joe Slovo, Joe Nhlanhla, Jacob Zuma, Sizakele Sigxashe, Simon Makana, Tony Mongalo and Daniel Oliphant.16 Oliver Tambo, Maharaj, Slovo and Chris Hani’s fear of political marginalization served as the unspoken, secret catalyst and incentive for Operation Vula, which was not initiated and implemented to support and protect the democratic negotiation process in South Africa. After De Klerk disbanded the ANC and SACP in February 1990, Hani remarked: “Nothing has changed. We need to infiltrate more cadres and arms into the country.”17

Vula’s clandestine communication systems

According to Jenkin, a communications operator in Operation Vula, there were no effective underground structures for the ANC-SACP in South Africa before the establishment of Operation Vula, because there was no leadership in the country. Jenkin argues: “Key leadership figures had not been sent into the country because it had always been deemed too dangerous to do so. There was a kind of vicious circle in operation: leaders could not go in because there were no underground structures in place to guarantee their safety; the underground structures could not develop because there were no key leaders in the country.18 Moreover, there was no form of secure communication between the ANC leadership abroad and local units. Before the objectives of Operation Vula could be implemented, the gap regarding secure communication between the ANC/SACP leaders in Lusaka and Vula operators in South Africa had to be solved.

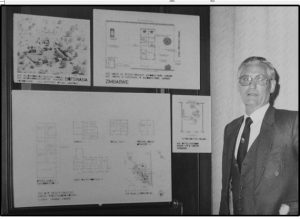

A South African government official displaying the plans and layout of ANC/SACP offices and facilities in Botswana, Zimbabwe and Zambia during a news conference in Pretoria in May 1986. Operation Vula was compromised by an infiltration agent in Lusaka, Zambia. Vula was planned and initiated in the ANC’sheadquarters in Lusaka and Vula’s operational leaders in South Africa.”19

After years of experimenting, Jenkin in London succeeded in setting up a secure communication system, making use of British telephone lines which compromised the operation. Audio codes were recorded, played during a call on public telephones, re-recorded on the receiver’s side and decrypted by means of a computer program. He was approached by Maharaj by 1987 to refine his communication system for Operation Vula.20

Further improvements were made to the communication system and were ready for launch by July / August 1988 of Operation Vula, during which the first operators, including Maharaj and Kasrils, would be smuggled into the country.21 Jenkin instructed Operation Vula members in the use of the communication system that facilitated communication between Vula operators in South Africa, London, Lusaka and Amsterdam. Vula operators in South Africa could therefore also send coded messages to London, Lusaka and Amsterdam. The British government of Margaret Thatcher and SIS (British Foreign Intelligence Service) were aware of the ANC-SACP’s communications system that used the British telephone service as a basis. Despite economic, military and political sanctions against South Africa, there was a close intelligence liaison between the NIS and a variety of foreign intelligence services, including the British, French, Portuguese and German services. This collaboration included sophisticated electronic interceptions and TECHINT. Jenkin later said that Vula agents in London were convinced that the British intelligence service was watching them. A member of the British Parliament made allegations against Jenkin at one stage, claiming that he was making bombs in collaboration with the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and exporting them to South Africa.22

Maharaj and Nyanda were the first Vula agents to enter the country. Extensive plans were made in advance to make them disappear from the proverbial radar. Maharaj traveled to the Soviet Union behind the scenes of medical treatment, while Nyanda would also travel to that country for a long officer course. They were equipped with various disguises and false documentation before traveling from the Soviet Union, via a confusing route, first to various European cities, and then to East Africa and finally Swaziland. From Swaziland they were assisted in crossing the border into South Africa. In early August 1988, Jenkin received the first voice message received from Maharaj. The agents reached their destination and an excited delighted Jenkin informed the ANC leadership in Lusaka about the news.

With the help of a KLM air hostess who acted as courier for Operation Vula, the ANC-SACP operators in South Africa obtained a radio telephone (which preceded the modern cellphone). Before long, the lines of communication were virtually open between Vula agents in South Africa and London, where Jenkin was awaiting messages. About the reception of the first full-fledged secret and coded message that Jenkin received from Maharaj from South Africa, he writes years later as follows:

“Then suddenly on the last day of August, as I was sitting hacking away at another program on my computer, the “receive” phone started ringing. The answering machine played its usual outgoing message and then the yellow “receive” light came on, followed by the familiar high-pitched tone of a computer message. It was music to my ears. I tried to picture Mac cowering inside the acoustic hood of some grubby public telephone in Durban. I could see him nervously holding the little speaker against the mouthpiece of the phone while looking worriedly over his shoulder. His heart must have been racing like mine. It was hard to believe that the sound I was hearing so clearly was coming from a small tape recorder ten thousand kilometres away. I quickly played back the message into my computer and proceeded to decipher it. As the plaintext message appeared on the screen I leapt for joy. There it was – Vula’s first message – as clear as daylight. Now we’re in business!”23

With this, Operation Vula was in full swing and in the meantime Maharaj continued, among other things, to start a propaganda project in South Africa.

Tim Jenkin, a comminications operator involved in Operation Vula in London.

Jenkin was now under the blisful impression that a direct communication links had been estabiished between the ANC/SACP’s ‘generals’ in Lusaka and their ‘soldiers’ within South Africa. “I had seen comrades packing light weaponry when I was in Lusaka in June 1988, but now they were asking for an arsenal: AKM automatic rifles, TNT, detonating cords, hand grenades, RPG rocket launchers and rifle silencers, amongst other things. Any ideas that I’d had about Vula being purely a project to get political leadership into the country were quickly dispelled. This was serious stuff.24

According to Jenkin, the communication system between the agents in South Africa and the ANC leadership in Lusaka worked well and there was now a real dialogue between the “soldiers” and the “generals”. Requests for funds and additional communications equipment were commonplace, Jenkin said, but when the request for weapons was received, he was shocked:

By April 1989, Maharaj had suggested that Operation Vula contact Nelson Mandela directly. Mandela was detained at that time in a house on the grounds of the Victor Verster Prison outside Paarl. Since May 1988, he has had several meetings with a small team of government officials – including Niel Barnard of NI. These first talks took place in strict secrecy and in the NI the project became known as Gentle Neelsie (Sagmoedige Neelsie).25

Later, Mandela and other senior ANC members, such as Thabo Mbeki, would declare that they were not aware of Operation Vula.26 Mbeki’s outrage at the exposure of Operation Vula contradicts his later admission that he felt “undermined” by the Vula group.27 At the time of Vula, Mbeki was a member of the SACP’s command council and chaired the SACP’s Seventh General Congress held in April 1989 in Havana, Cuba. During this congress, Slovo’s document, “The path to power”, was unanimously approved.28 In this document, the SACP once again committed itself to an armed uprising and takeover of power in South Africa.

The plans to allow Mandela to communicate directly with the ANC leaders from detention were passed on to Mandela via his lawyer (who visited him regularly). Although Mandela, according to Jenkin, did not immediately agree to take part in Vula, he was later persuaded. Jenkin writes about it like this:

“Suddenly one day a message from Mandela appeared on my screen. I stared at it for a long time. It was not the content that excited me but the very fact that here, for the first time ever, was an electronic message from the mythical man who had inspired us all so much. A real live message from Mandela here on my computer screen. Vula’s ultimate coup!29

The communication system was expanded and renewed over time and by the time the ANC was unbanned, it was decided to continue with Operation Vula. “Vula now moved into top gear,” Jenkin stated in a magazine article.

There was no slowing down of activities related to Operation Vula until much later in the year [1990], well after negotiations between the ANC and the regime had got under way. The high point of Vula was reached in the middle of the year, only to be brought down by the arrests of a number of key activists in July.30

In the months following the disbandment of the ANC, an increasing number of weapons entered South Africa through Operation Vula. The role of the underground activities was debated in ANC ranks, but it was decided to maintain the underground plans as a so-called “insurance policy”, should negotiations with the government be unsuccessful. This “policy” had to be offered by the underground ANC and, Jenkin writes, “it had to be a strong underground, not one that had no weapons at hand” .31 By June 1990, plans had been drawn up for the “return” of Kasrils and Maharaj to South Africa, so that they could attend meetings of the ANC’s National Executive Committee (NEC) as part of the disbanded. At that time, both were secretly working in the country, but to save their prestige, they first had to return abroad to come to South Africa later as returning exiles. However, Operation Vula’s plans were overturned after an infiltration agent informed South African authorities of the existence of the operation. Operation Vula was also confirmed by a second agent, followed by a series of arrests in July 1990.

The compromise of Operation Vula

During the first weekend of July 1990, two underground ANC agents were arrested in Durban. Several incriminating items were found in their possession, including information on ANC shelters and safe houses, agents and collaborators and weapons depots. In the following week, a further forty ANC-SACP members linked to the operation, including Nyanda, were arrested.32 Maharaj was arrested on 25 July and weapons seized at a number of depots.33 Ronnie Kasrils was placed under immediate surveillance when he entered South Africa through the then Jan Smuts International Airport, he managed to escape the police. Kasrils and Maharaj were placed under continuous surveillance during Operation Vula and all their contacts, shelters and networks were compromised in this way.

On October 29, 1990, Maharaj, along with eight other Vula operators, were charged with terrorism.34 The government indictment showed that the arrest of the Vula operators was the end of five years of intelligence investigations and that the Security Branch and the NI were all from knew the failed Operation Vula. Mo Shaik, the later director-general of the South African Secret Service (SAGS), was in charge of Vula’s operational intelligence and his meetings with Maharaj led to the arrest of both. In the book, ‘Shades of difference: Mac Maharaj and the struggle for South Africa,’ Padraig O’Malley states that Maharaj and the ANC / SACP were blissfully unaware of the extent to which they had been infiltrated.35

Confrontation

De Klerk was furious when he was informed by the NI about Operation Vula on 13 July 1990. On July 26, 1990, he confronted Nelson Mandela about this underground operation and laid evidence before him on the table.36 De Klerk later remarked that Mandela was “apparently genuinely surprised” by the revelations and said that he intended to discuss the matter with Joe Slovo.

De Klerk considered the ANC’s abortive attempt to deploy an underground network in South Africa to be contrary to the conditions of the Groote Schuur minute37. He questioned the ANC’s public claims to negotiate peacefully and questioned the ANC’s commitment to a peaceful settlement through the negotiations.38

The exposure of Operation Vula and the ensuing media storm resulted in both main parties in the negotiation process being under greater public pressure to sign the Pretoria Minute on 6 August 1990.39 In this agreement, the ANC / SACP undertook, inter alia, to to suspend thirty years of armed struggle, a decision that could be considered a feather in De Klerk’s cap.

Slovo dismissed Operation Vula as a thing of the past with a Sorge-me-not attitude.40 Mandela was apparently pleased with this explanation and later paid tribute to the ANC-SACP members at a rally in June 1991. was involved in Operation Vula. In his speech on Operation Vula, Mandela said, among other things, that the Vula operators “were acting on the instructions of the ANC […] I am pleased to take this opportunity to present them to the public and I welcome them to the overt, legal structures of the ANC ”.41 He also argued:

“Vula and other similar projects did not in any way constitute the pursuance of a double agenda, nor did they constitute actions inconsistent with our search for a negotiated resolution. [If] anything, they strengthened negotiations rather than undermined them.”42

Operation Vula ended in an anticlimax in March 1991, when the government withdrew charges against Maharaj, Nair, Nyanda and six other Vula operators under the Great Minutes and Pretoria Minutes. The government also granted an unconditional waiver to the rest of the Vula operators and undertook not to prosecute them further.43

Vula’s weak links

Vula operators ignored two basic operational espionage principles which led directly to the arrest of its operators and collaborators; ie never to use a telephone, cell phone or laptop in any clandestine communication system and secondly never to withdraw money from an ATM (ATM). Phones and bank withdrawals are clear indicators, signals and markers for counter-espionage investigators, because they are so easy to monitor and intercept.

Kasrils was one of the Vula operators placed under continuous surveillance, monitoring and pursuit because he used an ATM card to withdraw money. Members of the NI monitored Kasrils’ movements and at the same time resisted pressure from the Security Branch who demanded that Kasrils be arrested. Kasrils nonchalantly met with contacts and comrades, compromising their identities in the process and facilitating their arrests.

Vula members did not comprehend and underestimated the sophisticated interception methods of the NIS satellite interception facilities. The NIS’s computer – driven cryptographic creation system registers any names, telephone numbers, personal details, electronic communications activities and word combinations that are of interest to the intelligence service. It is therefore impossible for any individual not to be tracked down.

On the other hand, the ANC’s communication was relatively primitive and used a one-letter block approach. The only difference was that Jenkin computerized the old-fashioned one-block letters using two old Toshiba T1000 and T3100 computers. That would make decryption theoretically impossible, but interception relatively easy.44 The NIS obtained the crypto keys used by Operation Vula through satellite interception and was thus able to comfortably monitor communication between the respective operators. The ANC / SACP completely underestimated the NI’s technological methods of gathering information. Unaware that their clandestine communication system had been compromised, Vula operators moved from city to city and with it all their plans of an armed insurrection in South Africa went up in smoke.

A Toshiba J3100 computer, similar to the one used in Operasie Vula

contacts identified and networks blown.45 The South African government monitored the course of Vula for three years to gather as much information as possible about the ANC’s networks and modus operandi. It would serve no purpose to arrest Kasrils, Maharaj and Nyanda in the early stages of the operation, but rather to simply pursue and monitor them until all their networks, shelters and contacts have been identified. The unveiling of Operation Vula took place after the lifting of the state of emergency in South Africa in July 1990.46 This was a serious embarrassment for the ANC / SACP and raised questions about the ANC’s integrity during the negotiation process and their commitment. to a constitutional settlement. Despite the weak links, Operation Vula succeeded to a limited extent in that some of the ANC members, including Nyanda and Maharaj who received advanced training in espionage techniques from the East Germans, Cubans and Russians, entered the country unnoticed. After that they found themselves in Durban279 where they proceeded with the planning of Operation Vula

Was Operation Vula a success, or not?

All the arrested Vula operators were released on bail of about R300 000 on 8 November 1990. On March 22, 1991, the accused were acquitted of prosecution and with that the case against Operation Vula agents came to an end. Jenkin later stated that the operation was still active until early that year.47

The ANC, and especially the SACP, spent a lot of time, energy and labor on Operation Vula without deriving any intelligence or strategic benefits from the operation. The arrival of Operation Vula in 1990 was untimely and uncomfortable for the ANC / SACP, because it took place after the disbandment of the ANC, but before the start of the formal negotiation process between the government and opposition groups. “It was ‘untimely’ because it occurred after the painstaking process of planning, but before the plans could be implemented,” said the later director-general of the Department of Military Veterans, Tsepe Motumi, written in 1994.48

ANC propagandists claim that Vula was the most successful ANC intelligence operation ever, because the ANC succeeded in establishing an alternative intelligence structure not only within the ANC, but also within South Africa. What exactly was achieved with Operation Vula? The unscrupulous actions and imprisonment of Vula’s operators have caused uproar in South Africa and internationally, undermining the ANC’s moral negotiating position – not promoting or strengthening it. The compromise of Vula was one of the reasons for the signing of the Pretoria Minute in which the ANC / SACP committed itself to the elimination of the armed struggle, that is to say, actually the opposite as the objectives of Operation Vula.

An ANC report called “Report of the Department of Intelligence and Security (DIS) to National Conference, December 1994, makes no mention of Operation Vula. The purpose of this report, according to Shaik, was an audit of the DIS’s activities from 1991 to 1994, the period in which Vula took place. It is therefore strange that the great “intelligence success” of the ANC / SACP is not mentioned at all. In addition, a further ANC submission to the Truth and Versus Commission (TRC) on the operational work of the DIS also made no mention of Operation Vula.49

The ANC / SACP, after Vula, through Mathews Phosa, indicated that they did not know where the weapons and weapons depots of Operation Vula were.50 This confession could mean two things: firstly, that the storage of weapons within the borders of South Africa by Vula operators were merely blindfolding and boasting, or that the weapons were smuggled in, but that the ANC / SACP lost control of them after 1994.

The inherent weakness of Vula was the ANC / SACP’s tactical mistake of trying to implement this operation just before the start of direct, bilateral talks between the South African government and former freedom movements. In the era and context of the early 1990s, Operation Vula, like its ideological predecessor, Operation Mayibuye, thus had little influence or effect on the strategic political balance of power in South Africa. It is highly doubtful whether Operation Vula had any effect on De Klerk’s efforts to persuade his cabinet, the NP or the security forces, including the South African Defense Force (SADF), to share power – and by implication ‘ a black majority government – to be accepted in South Africa.

Intelligence services do not disclose their successes and achievements, while failures, shortcomings and inability are often hung on the big bell by the media and uninformed politicians. The NIS’s policy was to always maintain a low profile, to protect their operational resources under all circumstances, which might be identifiable by inference.

The role players in Operation Vula

- Oliver Tambo: As president of the ANC, he approves Operation Vula.51

- Joe Slovo: As commander of MK, he approves of Operation Vula; he was also at that time the general secretary of the SACP.52

- Mac Maharaj: One of the leaders of Operation Vula. He later became Minister of Transport and the presidential spokesperson.53

- Jacob Zuma: As head of the ANC’s Department of Intelligence and Security (DIS), he has direct knowledge of Operation Vula and was considered an important driving force behind the establishment of the operation.54

- Pravin Gordhan: Arrested in 1985 by the security services for his activities in the Natal Indian Congress (NIC) and the ANC. In 1986, Gordhan continued his political activities underground and in 1990 he was arrested as one of the Vula operators. Gordhan, a member of the SACP, later became commissioner of the South African Revenue Service (SARS) and later Minister of Finance. He is currently the Minister of Public Enterprises.55

- Ronnie Kasrils: Joined the SACP and MK in 1961 and was a respected member of Operation Vula who entered the country in secret during the operation. During the prosecution of other Vula members, he escaped arrest and was acquitted in 1991.56 In 1992, he (along with Chris Hani and Cyril Ramaphosa) was involved in the Bisho massacre when a group went to the Cisque city of Bisho ( Bhisho) advanced to demand the resignation of military leader Oupa Gqoso. The Ciskeise army fired on the group and 28 people were killed. Kasrils was later appointed Minister of Intelligence.57

- Ivan Pillay: One of the lesser known Vula operators. Pillay left South Africa in 1977, just after the Soviet Union, to undergo military training as a member of MK in Swaziland (now known as Eswatini) and Mozambique. From 1980 to 1985, Pillay was section chief of MK’s Mandla Judson Kuzwayo unit and then a member of the ANC’s Internal Reconstruction and Development Committee (IRDC). Pillay later became a member of the SACP’s central committee and after his return to South Africa he was appointed director of the Chief Directorate Foreign Operations of the South African Secret Service (SASS). Gordhan appointed him to a senior position in SARS in 1999 with the task of setting up a secret investigation unit to investigate the so-called illegal economy in South Africa. Pillay later was both deputy and acting commissioner of SARS.58

- Siphiwe Nyanda: Nyanda, also known as Ghebuza, was born in 1950 in Soweto. He joined MK in 1974 and left South Africa in 1975 to undergo military training in East Germany. Nyanda became a staff member of MK in the Transvaal in 1983. In June 1988, he and Maharaj secretly entered the country and worked underground until he was arrested in July 1990. He is charged with, among other things, terrorism, but all charges were dropped in 1991.59 He served as head of the South African National Defense Force (SANDF) from 1994 to 2005 and was Minister of Communications from 2009 to 2010.60

- Chris Hani: Hani was born in Transkei in 1942 and joined the ANC Youth League as a teenager. In 1961 he joined the SACP and a year later became one of the first MK volunteers and underwent training in 1963 in the Soviet Union. After this he was continuously involved in the activities of the ANC, MK and SACP and was appointed head of MK in 1987.61 During Operation Vula he was involved in the establishment of weapons depots and underground command structures of the ANC / SACP in South Africa.62 He became leader of the SACP in 1991 and was shot dead by Januzs Walus in front of his house in Dawn Park, Boksburg in 1993

- Nathi Mthethwa: Mthethwa was born in 1967 and during the 1980s was involved with the Klaarwater Youth Organization and the food workers’ union FAWU. In 1988 he was recruited as a member of Operation Vula, but arrested in 1989. He later became, among other things, regional secretary of the ANC Youth League. From 2008 to 2009 he was Minister of Safety and Security and served from 2009 to 2014 as Minister of Police. He is currently the Minister of Sport, Arts and Culture.63

- Solly Shoke: Shoke was born in Johannesburg and joined MK shortly after the 1976 uprisings. He later progressed to MK commander. He underwent military training in Angola and subsequently became involved in Operation Vula. Shoke was appointed head of the South African National Defense Force (SANDF) in 2011.64

- Billy Nair: This SACP member was born in Durban in 1929 and has been involved in trade unionism since the 1950s. In 1949 he joined the Natal Indian Youth Congress, and later the parent organization, the Natal Indian Congress. He was arrested in 1956 and charged with high treason along with 155 other ANC leaders and related organizations. In 1963 he was charged again, this time with sabotage, and sentenced to twenty years in prison, which he served on Robben Island. Nair was released in 1984, but continued his activism and became involved in Operation Vula. He was arrested in 1990 along with other Operation Vula members, but again eleased. After 1994 Nair served for two terms as a member of the national assembly of South Africa.65

- Max Ozinsky: Already in 1986, as a student at the University of Cape Town, Ozinsky worked actively as an anti-apartheid activist and in 1987 underwent intelligence training in Moscow. He was a member of the National Union of South African Students (Nusas) and MK member who as a young operator and member of Operation Vula was intimately involved in the planning and execution of the operation on the Cape Peninsula. Ozinsky was arrested in 1990 along with other Vula operators, but released. He was later appointed a member of the provincial parliament in the Western Cape for the ANC.66

- Charles Nqakula: Nqakula joined MK in the mid-1980s, and by 1988 infiltrated South Africa as commander of Operation Vula to establish underground structures for the ANC in South Africa. He was not arrested along with the other Vula operators, and only emerged in 1991 after the case against the Vula operators was dropped. After Hani’s assassination in 1993, he became head of the SACP and was also appointed to the ANC’s National Executive Committee (NEC) in 1994. He was appointed Deputy Minister of the Interior in 2001, after which he served as Minister of Security and Security from 2002 to 2008 and from 2008 to 2009 as Minister of Defense.67

- Mo Shaik: As a student activist, Shaik became involved in anti-apartheid projects and joined the United Democratic Front (UDF) in the 1980s. In 1987 he underwent intelligence training in East Germany and then established an intelligence unit in Natal. He was head of Operation Vula’s internal intelligence leg and worked closely with Maharaj.68 He was a member of MK as well as the ANC’s DIS.69 Shaik was South Africa’s ambassador to Algeria from 1999 to 2003, appointed head of the SASS in 2009 (responsible for foreign intelligence). The SASS was merged with other intelligence units in 2009 to form the State Security Agency (SVA ).70

- Charles Ndaba: Operation Vula Operator, arrested in Natal in July 1990.71

- Mbuso Shabalala: Operation Vula Operator, arrested in Natal in July 1990.72

- Raymond Suttner: ANC / SACP member; support agent for Operation Vula

- Connie Braam: Former chairperson of the Anti-Apartheid Movement Netherlands (AABN) who supported ANC members and Operation Vula operators with housing and courier services.73

- Janet Love: Acts as communications operator for Operation Vula. She later applied for amnesty for the illegal possession and distribution of weapons during that operation. Amnesty was granted to her in 2000.74

- Tim Jenkin: Anti-apartheid activist who was arrested in 1978, but escaped from Pretoria Central Prison in 1978.75 After his escape, he went to live in London and continued his underground activities for the ANC. He works during Operation Vula as a communications operator.76

*

References and Footnotes available on request.

‘Spioenmeesters’, a book by Henning van Aswegen on South African intelligence operations in Africa and Europe, is available on Amazon.com

Baie geluk aan Henning van Aswegen met hierdie deeglik nagevorste artikel oor Operasie Vula van die laat tagtiger- en begin negentigerjare. Hy dui die beplanning en uitvoering van Operasie Vula oor etlike jare volledig aan en vra dan met reg die vraag of dit doeltreffend was?

Die titel van sy artikel “a deadly miscalculation” beantwoord hierdie vraag. Dit sou ook nie so ’n “deadly miscalculation” gewees het as ons verskillende staatsveiligheidsafdelings nie daardie tyd steeds so doeltreffend was nie om operasie Vula oor vyf jaar te monitor sonder dat die anderkant daarvan geweet het.

Vergun my drie verdere opmerkings.

1. Dat die onderhandelinge en ’n skikking in die negentigerjare nodig was, word nie betwis nie. Daar was nie meer baie alternatiewe oor nie. Ek was ook by groot gedeeltes van die onderhandelinge teenwoordig. My frustrasie was al die geleenthede, waarvan ek getuie was, wat gemis is en waarmee ’n beter skikking en ’n meer wen-wen oplossing verkry kon word.

Operasie Vula is een so ’n voorbeeld. Daar kan geen twyfel wees dat Oprasie Vula hoogverraad was en dat die betrokkenes daarvolgens gestraf sou kon word nie.

Operasie Vula het alles van ’n vreedsame onderhandelingsproses soos wat tussen die NP-regering en die ANC by die Groote Schuur minuut ooreengekom is, verbreek. Die ANC het met eier op die gesig gesit. Tog eis die ANC op arrogante wyse dat ANC lede soos Maharaj en Nyanda, wat in hegtenis geneem is, amnestie moet kry en vrygelaat word.

FW de Klerk het ook ’n dilemma gehad deurdat dit logies was dat sonder amnestie dit tot ’n uitgerekte hoogverraadsaak sou lei wat die onderhandeling sou beëindig of op die minste dit met maande sou vertraag.

Die Polisiehoofde sien hierdie dilemma raak en maak voorstelle hoe dit ten beste benut kan word. Hulle eis dat as amnestie gegee gaan word aan die Vula-oortreders, die geleentheid benut moet word om ook amnestie te gee aan alle polisielede wat oor die jare by die gewelddadige konflik betrokke was. Die ANC was met sy rug teen die muur en kon dit nie weier nie.

Die ongelooflike gebeur deurdat Minister Kobie Coetzee dit af skiet. Volgens hom moet sekere politieke belange eers beskerm word voordat algemene amnestie op die tafel geplaas kon word.

Generaal Johan van der Merwe, polisiehoof, skryf later in sy boek (p.172): “Dit het later duidelik geword dat die politieke belange waarna mnr. Coetsee verwys het, bloot gegaan het om die beskerming van die politieke toekoms van regeringslede. Die belange van die veiligheidsmagte het hulle geensins getraak nie.”

Die gevolg hiervan is dat twee bejaarde oud lede van die Veiligheidspolisie (Engelbrecht en Stander) onlangs aan moord in 1987 skuldig bevind is. Nog 159 soortgelyke sake word blykbaar tans volgens minister Kubayi ondersoek.

Ek het nie al die detail van die 1987 aanklagte teen die veiligheidspolisielede nie maar ek weet dat Robert McBride amnestie gekry het nadat hy gevonnis is vir drie moorde in 1986 op onskuldige persone by die Magoo’s Bar. So ook Mzondeleli Nondula wat skuldig bevind is aan ses moorde op die onskuldige De Nysschen en van Eck families in Messina. Hy het twee polisielede doodgeskiet en die kleuters van die families se liggaamsdele is in die boomtakke gevind nadat die myn wat hy geplant het, afgegaan het. Daar is nog talle voorbeelde.

Meer as 20 000 ANC lede het so amnestie gekry en is vrygelaat voor die Waarheidskommissie nog gesit het as voorwaarde van die ANC vir onderhandelinge. Hierdie dubbele standaarde maak my woedend en is uiters onregverdig. ’n Belangrike geleentheid om algemene amnestie te kry deur Vula as onderhandelingshefboom te gebruik, is gemis.

McBride was later hoof van die buitelandse tak van die Staatsveiligheidsagentskap en hoof van die Suid-Afrikaanse Polisiediens se Onafhanklike Ondersoekdirektoraat. Nondula het na 1994 ’n kolonel in die weermag geword.

2. Onlangs het oud-president Zuma se dogter, Duduzile Zuma-Sambudla, uit die parlement bedank weens haar betrokkenheid om 17 Suid-Afrikaners te werf vir die oorlog in die Oekraïne. Jacob Zuma verduidelik in ’n brief aan die Russies Minister van verdediging, Beloesof, dat die 17 na Rusland is vir opleiding as offisiere en nie om in die oorlog te veg nie.

Zuma skryf hulle is gestuur “om gevorderde militêre opleiding te ontvang. Hul missie was om van die wêreld se bestes te leer sodat hulle eendag na Afrika kan terugkeer as bekwame leiers en standvastige kampvegters vir ons gemeenskaplike saak.”

My vraag is: Waarom ”militêre opleiding” in Rusland en vir watter “gemeenskaplike saak?” Dit lyk en ruik na ’n nuwe, maar baie amateuragtige poging vir ’n operasie Vula. Veral gesien teen die agtergrond van Zuma se betrokkenheid en kennis van die eerste Operasie Vula.

Later is verduidelik dat hulle vir “militere opleiding” gestuur is om hier beskermers van belangrike persone te kan word. Ons het meer as genoeg sulke opleidingsgeleenthede in Suid-Afrika.

Die feite is dat die polisie in Julie 2021 nie kon keer dat duisende protesteerders winkels plunder en mense doodmaak hoofsaaklik in KZN nie. Die doel, is later verduidelik, was om die land onregeerbaar te maak. Zuma-Sambudla was ook daarby betrokke. Dink iemand dalk dat met beter militêre opleiding hierdie 2021 gebeure herhaal kan word om so met geweld van die huidige ongewilde Ramaphosa regering ontslae te raak? Hopelik neem die regering kennis van hierdie saak.

3. Suid-Afrika is trots op sy demokrasie. Die vraag is of Suid-Afrika die finale toets vir ’n demokrasie al geslaag het?

As ek na standpunte van Zuma se dogter, Duduzile Zuma-Sambudla, van MK- en EFF leiers luister, is ek nie seker nie.

Die finale toets kom wanneer president George H.W. Bush van die VSA die sleutels van die Withuis, en so die regering aan die nuwe president Bill Clinton (van ’n ander politieke party) oorhandig na ’n demokratiese verkiesing en hom vriendelik die Withuis en “Oval Office” wys. Of Jan Smuts as leier van die “Sappe”, wat minder gewillig maar steeds, die Uniegebou se sleutels in 1948 aan dr. DF Malan, leier van die “Natte” oorhandig.

Prof K.A. Busia van Ghana het die volgende oor demokrasie in Afrika geskryf:

“A democracy in the last analysis depends on the character of individual men and women and the moral standards of the community. Rules governing elections may be made; freedoms may be provided in constitutions; and Bills of Right may be passed; they will make arbitrary acts easier to resist publicly, but they will not by themselves secure democracy. There are other rules which are unwritten, such as honesty, integrity, restraint and respect for democratic procedures.”

Ek het so gevoel dat daardie toets vir die ANC en vir Suid-Afrika nie meer ver die toekoms in is nie.

Dankie Henning van Aswegen vir hierdie deeglike artikel en vir jou lekker lees boek Spioenmeesters waaruit hierdie inligting kom.

Pieter Mulder