Abstract: Joan Swart, CapeXit NPO, Global Power, Africa and the 21st Century, African Strategic Alignments, African economic battlegrounds

Dr Joan Swart – CapeXit NPO

Africa as the Silent Battleground of Global Power: Strategic Alignments, Sub-State Fault Lines, and the Contest for the 21st Century

Africa Is the Quiet Frontline of a Global Power Contest

While the world’s attention is consumed by the fires of Gaza, Ukraine, Taiwan and Venezuela, another contest — slower, quieter, and arguably more decisive — is unfolding across the African continent. It is the contest for strategic footholds, defence access, resource routes, multilateral alignment, and political influence.

Africa is no longer a geostrategic periphery. It has become one of the most valuable arenas in which global power is being projected and negotiated. From military cooperation agreements in the Sahel, to port refurbishments on the Indian and Atlantic seaboards, to mineral dependencies in the Congo Basin, the great powers are quietly investing in long-term leverage rather than short-term headlines.

And African governments know it.

They are bargaining, not being bought.

They are calculating, not compliant.

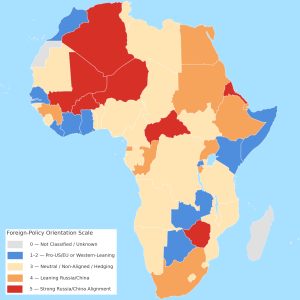

A simple continental alignment map — rating national leanings toward the West or toward Russia/China on a 0–5 scale — makes visible what diplomatic communiqués and press statements conceal: Africa is strategically divided, ideologically fluid, and increasingly pivotal in determining what the next three decades of the world order will look like.

Africa is where power is moving before the world realises that it has.

Foreign-policy orientation index of African states (0–5 scale), reflecting relative alignment based on defence partnerships, strategic cooperation agreements, multilateral voting behaviour, and critical infrastructure exposure to Western or Russia/China influence pathways.

Strategic Distraction and Opportunity

The West’s strategic bandwidth is finite. Domestic polarisation, economic shocks, energy insecurity, supply-chain fragility and ongoing foreign wars have eroded diplomatic capacity. Russia and China understand this. They recognise that at the very moment when the West is absorbed by highly combustible crises elsewhere, Africa presents an opportunity for patient, incremental geopolitical gains.

China’s strategy is infrastructural, economic, and increasingly dual-use. It is visible in the redevelopment of deep-water ports from Djibouti to Bagamoyo, majority financing of rail systems such as the Addis–Djibouti corridor, telecommunications dominance through Huawei 5G networks, mineral dependencies through chromium, lithium, cobalt and rare-earth concessions, and cooperation agreements around sensitive military facilities and officer training in countries such as Cameroon, Zimbabwe and South Africa.

Russia’s approach runs through arms procurement, training missions, paramilitary support, election assistance, information operations, and diplomatic cover. In Africa’s Sahel belt, a near-complete displacement of French and UN-linked security arrangements has unfolded in less than five years — replaced by a Russian-centred architecture that trades security for regime survival.

Western partnerships, by contrast, are still built primarily on institution-building, governance norms, human rights frameworks and conditional financing. The result is a three-way marketplace for influence — and many African governments are simply choosing what serves their security and strategic autonomy best.

Which is why the majority cluster on the map is neither blue nor red, but beige: the hedgers, the balancers, the negotiators.

Africa’s Loyalty Belongs to No One

The Cold War template — alignment by ideology — is gone. Today, African foreign policy is largely driven by access to financing, regime stability, trade corridors, technological capability, and strategic leverage. The map’s central zone, representing non-aligned or hedging states, is the most revealing. These governments are not indecisive; they are attempting to preserve manoeuvring space in a world where being captured by any single bloc carries long-term risk.

Africa has bargaining power for the first time in generations — because the world wants in. And African leaders are negotiating accordingly.

The Sub-Surface Shift: Security Partnerships, Defence Access, and Quiet Entrenchment

Below formal treaties and diplomatic communiqués lies a more sensitive layer: long-term strategic entanglement. Russia and China are establishing pathways to influence that are difficult to unwind once embedded — defence supply chains, joint training, counter-terror agreements, cyber infrastructure, extractive concessions, naval access, satellite cooperation, nuclear partnerships, and financial linkages.

These are the slow-moving tectonics that may determine the direction of African foreign policy long after today’s political leaders are gone.

As press attention focuses on Gaza ceasefires, Ukrainian front lines or Taiwan’s election cycles, the great powers are quietly deepening their footprint on the African continent, often beneath public awareness and outside conventional diplomatic scrutiny.

South Africa is a case in point. Beyond BRICS rhetoric, there are unpublicised exchanges around military facilities, officer training, intelligence collaboration and strategic port infrastructure. These forms of access, once normalised, tend to influence later policy decisions — whether on defence procurement, voting positions in multilateral forums, maritime doctrine, or data-sharing obligations.

This is geopolitical gravity, not geopolitics by press release.

Beyond the Borders: Western Sahara, Somaliland, and the Western Cape

One of the most under-analysed trends in African geopolitics is the growing strategic significance of politically distinct sub-state regions — polities whose values, strategic instincts, or institutional cultures diverge from their parent states. These internal frontiers reveal where ideological, diplomatic and strategic fault lines really lie.

Three examples crystallise the point:

Western Sahara

A geopolitical pivot between Morocco, Algeria and external powers. Its unresolved sovereignty dispute shapes AU diplomatic alignments, energy and transport corridors in North Africa, and the region’s diplomatic posture toward Europe, China and Russia. The Western Sahara question is not frozen history; it is a strategic asset wielded by multiple actors.

Somaliland

A functioning, relatively democratic proto-state that increasingly attracts discrete engagement from Gulf actors, security partners and even Taiwan. It offers maritime relevance, stability, counter-piracy functionality and institutional coherence that Somalia struggles to provide. For external governments assessing strategic partnerships in the Horn, Somaliland is already a parallel doorway.

The Western Cape

South Africa’s most functional, economically resilient and institutionally stable province. With a markedly different governance culture, democratic ethos, fiscal discipline and strategic location, it represents a potential alternative interface for foreign engagement if South Africa’s national foreign policy deepens alignment with China and Russia. In global strategic calculations, dependable nodes matter as much as sovereign capitals.

The shared lesson is simple: Africa’s future geopolitical posture may not be uniform within existing borders. Regions with clarity of administration, infrastructure, maritime relevance and governance stability attract attention — especially from actors seeking reliable access points distinct from central political volatility.

Sub-state ambiguity, paradoxically, becomes strategic possibility.

The Map as Signal

Placed early in the discussion, the map visually captures this emerging reality.

It reveals not only how national governments align, but also where strategic vacuums, diplomatic fluidity and potential fault lines reside. The beige middle — the hedging zone — is the most consequential. That is where leverage lives. That is where external actors will contest hardest. And it is also where sub-state futures become geopolitically conceivable.

When embedded in defence thinking, the map becomes more than colour coding. It signals where bloc-shifts are likely, where maritime access interests converge, where supply corridors matter, where intelligence partnerships may emerge, where diplomatic recognition fights could intensify, and where future strategic realignment may occur during crises.

This is the silent pre-game of geopolitics.

Strategic Implications

For analysts, policymakers and military planners, several implications follow:

- Africa is no longer the passive recipient of foreign influence. It is an active diplomatic marketplace.

- Non-aligned states now command premium strategic value.

- Sub-state regions with stability, competent administration and maritime positioning invite quiet cultivation by great powers.

- Long-term defence access, infrastructure and security cooperation agreements matter more than public speeches.

Africa’s internal geography — political, cultural, institutional — is becoming as relevant to global strategic competition as its external borders.

This should recalibrate how outsiders read the continent: through the prism of influence pipelines, supply corridors, contested recognition zones and quietly negotiated defence relationships.

Closing Perspective

Africa is not the footnote to the strategic dramas unfolding elsewhere. It is the quiet board on which the new global contest for power, resources, access and institutional alignment is being conducted. The decisions made in African capitals — and potentially in autonomous regions like Western Sahara, Somaliland, or South Africa’s Western Cape — will shape the distribution of global influence long after today’s flashpoints have faded.

This is less about ideological allegiance and more about structural positioning. Maritime control, resource access, technological dependency, defence diplomacy and institutional resilience will decide who wins influence on the continent. Africa’s map today is not a static picture of current loyalties; it is a predictive model of emerging geopolitical gravity.

The real question is not which bloc “wins” Africa, but which African actors — sovereign or sub-state — will shape the terms of engagement.

The quiet moves being made today are the ones that will matter when the world looks back in twenty years.

Africa will not be won by noise, rhetoric, or crisis.

It will be won by patient presence, strategic partnerships, and the choices of governments — and regions — that know their own worth.

Dr Joan Swart is a forensic psychologist and security analyst with an MBA and an MA in Military Studies. Her work focuses on African security, geopolitics, state fragility, substate dynamics, and the intersection between governance, legitimacy, and coercive power. She is the author of several books and regularly publishes long-form analysis and opinion pieces on security and governance issues. Her writing has appeared in outlets including DefenceWeb, Maroela Media, Netwerk24, RSG, Visegrad, and other policy and public-affairs platforms. Dr Swart is a director of CapeXit NPO, where she conducts research and analysis on self-determination, regional governance, and security risk in Southern Africa. Her work bridges academic research, policy analysis, and applied strategic assessment.

*