SAA Flight SA 228: 20 April 1968: Windhoek

Wolfgang Witschas

Abstract

SA 228 was a scheduled South African Airways (SAA) flight from Johannesburg via Windhoek, Luanda, Las Palmas, London and Frankfurt, that crashed on Saturday 20 April 1968, shortly after take off from the JG Strijdom International Airport outside Windhoek, South West Africa (SAW) (now Namibia).

Key Words

South African Airways (SAA), Flight SA 228, Jan Smuts International Airport, JG Strijdom International Airport, Windhoek, Boeing 707-300C aircraft

Boeing 707-320C: Pretoria ZS-EUW,

date unknown

Introduction

Over Fifty years ago on Saturday 20 April 1968 South African Airways (SAA) Flight SA 228 was a scheduled flight from the then Jan Smuts International Airport, Johannesburg, South Africa, to Heathrow London, UK, with stopovers in Windhoek, then SWA, Luanda, Angola, Las Palmas, Canary Islands, London UK and Frankfurt, Germany. On 20 April 1968, the Boeing 707-300C aircraft, named “Pretoria” and registered as ZS-EUW, crashed into the ground shortly after take off from Windhoek’s Strijdom International Airport.

LIST OF CREW: Flight SA 228

Captain Eric Ray Smith

Flight Officer John Peter Holliday

Second Officer Richard Fullarton Armstrong

Flight Engineer Officer Pillip Andrew Minnaar

Navigation Officer Harry Charles Howe

Flight Traffic Officer A.G. Manson

Chief Flight Steward J.A. Erasmus

Senior Flight Steward H.S. LouwFlight Steward R.J. Bester

Flight Steward J.W. Jesson

Flight Stewardess M. Nortier

Flight Stewardess E. Janse van Rensburg

JG Strifdom International Airport (1965-1990)

Flight SA 228 had departed Johannesburg for the first leg of the flight to the JG Strijdom Airport, Windhoek, with 105 passengers and 12 crew members (totalling 117 people). After an uneventful flight arriving in Windhoek around 20:20 local time, 35 passengers disembarked and 46 boarded in Windhoek, mostly Germans from SWA, German visitors as well as business men. Some airfreight was unloaded and loaded, which is normal routine on these flights. There were approximately 36 German nationals on the plane according to German sources.

Aerial view of JG Stridom International Airport: Runway 08 in the background

*Remark:

The main runway at the former J.G. Strijdom Airport is designated 08, because of its orientation. The “08” indicates the runway’s direction is approximately 80 degrees (or roughly east) on the compass, allowing aircraft to take off and land in that direction”

The aircraft took off from Windhoek on runway 08* at 18:49 GMT (20:49 local time). It was a dark, moonless night with few, if any, lights on the ground (the airport is situated about 50 km east of Windhoek) in the open semi desert east of the runway; the aircraft took off into what was described in the official report as a “black hole”.

The aircraft initially climbed to an altitude of 650 feet (198 m) above ground level, then leveled off after 30 seconds and started to descend.

Fifty seconds after take-off, it flew into the ground in flight configuration at a speed of approximately 271 knots (502 km/h; 312 mph).

The initial impact was in a slightly left-wing-down attitude and the four engines, which were the first parts of the aircraft to touch the ground, created four gouges in the soil before the rest of the aircraft also hit the ground and broke up.

Two fires immediately broke out when the aircraft’s fuel tanks ignited. Although the crash site was only 5,327 metres (17,477 ft.) from the end of the runway, emergency services took 40 minutes to reach the scene because of rugged terrain. Nine passengers who were seated in the forward section of the fuselage initially survived, but two died soon after the accident, and another two a few days later, leaving a final death toll of 123 passengers and crew.

Many of the dead were still strapped in their seats when two farmers in the vicinity, first to reach the burning wreckage, arrived.

Accident Details:

• Date: 20 April 1968

• Time: 18:49 GMT (20:49 local time)

• Location: 5.3 km (3.3 mi) east of JG Strijdom International Airport, Windhoek, SWA

• Fatalities: 123 passengers and crew

• Survivors: 5 passengers

The pilots of South African Airways Flight SAA 228 didn’t respond effectively to the emergency due to several factors that contributed to the accident.

Loss of Situational Awareness: The crew had no visual reference in the dark, leading to spatial disorientation. They took off into a “black hole” with few lights on the ground, making it difficult to gauge their altitude and speed. Here’s what happened:

Cause of the Accident:

The investigation attributed the accident to a combination of factors, including:

Pilot Error:

Loss of Situational Awareness: The crew had no visual reference in the dark, leading to spatial disorientation. The co-pilot failed to monitor the flight instruments sufficiently to appreciate that the aircraft was losing height. The following causes probably contributed in greater lesser degree to the situation described above:

They took off into a “black hole” with few lights on the ground:

(a) take-off into conditions of total darkness with no external visual reference

(b) inappropriate alteration of stabilizer trim: The ground at the point of impact is approximately 100 feet lower than the point on the runway at which the aircraft took off

(c) spatial disorientation; pre-occupation with after-take-off checks

Incorrect Flap Retraction Sequence:

The pilots used a flap retraction sequence from the 707-B series, which removed flaps in larger increments than desirable for that stage of the flight. This led to a loss of lift at 600 feet above ground level

Difficulty with Instruments:

The crew experienced temporary confusion when reading the vertical speed indicator, which was different from the A and B series of the aircraft they were accustomed to. The drum-type altimeter was also notoriously difficult to read, and the pilots may have misread their altitude by 1,000 feet.

Flight Deck Distraction:

The following causes might have contributed in greater or lesser degree:

(a) temporary confusion in the mind of the pilot on the position of the initiial-lead vertical speed indicator, arising from the difference in the instrument panel layout in the C model of the Boeing 707-344 aircraft, as compared with the A and B models, to which both pilots were accustomed;

(b) the pilot’s misinterpretation, by one thousand feet, of the reading on the ambiguous drum-type altimeter, which is susceptible to interpretation on the thousands scale;

(c) distraction on the flight deck caused by a bird or bat strike, or some other relatively minor occurrence; It has not been possible to determine whether the captain or the first officer was handling the controls at the relevant time. There’s speculation about a possible bird strike or other minor occurrence that might have distracted the pilots.

Design Flaw:

Lack of a ground proximity warning system (GPWS) in the aircraft making it

difficult to gauge their altitude and speed

The effective cause of the accident was the human factor, and not any defect in the aircraft or in any of the engines or flight instruments.

Despite having a relatively experienced captain with 4,608 flying hours on the Boeing 707, the investigation concluded that primary fault lay with the captain and first officer, who “failed to maintain a safe airspeed and altitude and a positive climb by not observing flight instruments during take-off”.

Aircraft Information:

• Aircraft Type: Boeing 707-344C

• Aircraft Name: Pretoria

• Registration: ZS-EUW

• Age: 6 weeks old at the time of the accident

Account of an unknown witness

A witness, most probably one of the survivors (not Taylor) said the plane “started wobbling” as it left the runway during the take off at Windhoek. He said the plane veered sharply off course when it was about 600 feet off the ground. There was a sound of a muffled explosion. Seconds later, one of its port engines ablaze, the aircraft hit the ground and exploded. Remark: This information could not be verified by any other sources or confirmed by the authorities.

Similarities between the Windhoek crash and the London crash involving a Boeing 707 aircraft on 08 April 1968

In London, a British travel agency asked that the Boeing 707s be grounded until a thorough investigation is made. Simon Goodman, director of Simms Travel Agency, said the Southwest African crash was similar to a mishap involving a Boeing 707 at the Heathrow Airport in London two weeks ago on 08 April 1968. The aircraft lost a port engine and burst into flame soon after take-off, leading to a major fire after an emergency landing, in which five people tragically died.

Both the Windhoek crash and the London mishap occurred when the engines were running at full throttle, aeronautical experts said.

Aftermath

The accident led to significant changes in aviation safety regulations, including the requirement for Ground Proximity Warning

System (GPWS) systems in all turbojet aircraft.

Accident site of SAA 228

Accident site of SAA 228

Accident site of SAA 228

Accident site of SAA 228

A graphical illustration of the crash

Rescue Operation

The emergency services of the airport responded immediately to reach the accident scene. As the crash site was about 5 km east from the end of the runway in a dark and difficult-to-reach area, which complicating recovery operations.

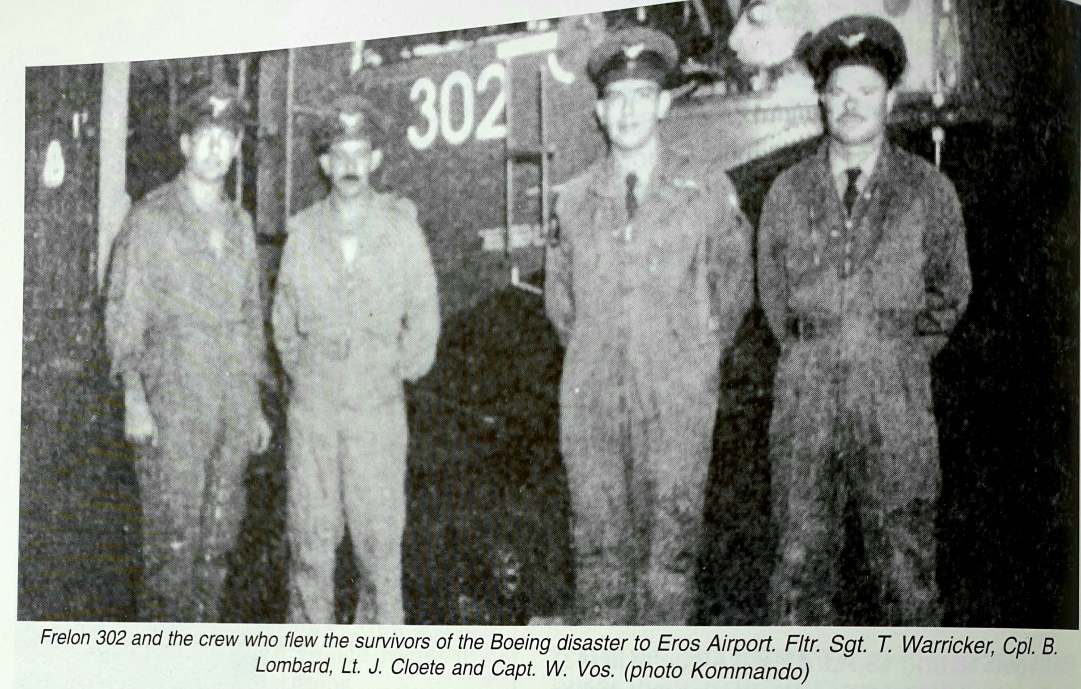

The airport authorities immediately contacted the management of the South African Police (SAP) in Windhoek. The then Divisional Commissioner for SWA, Brigadier Theo Crous. He instructed the SAP “Windhoek Flight” to sent both Sud Aviation Alouette lll helicopters to the accident scene. As the South African Air Force (SAAF) Detachment in Windhoek, commanded by Commandant Black, had a Sud Aviation (SA) 321L Super Frelon transport helicopter stationed also at the Eros Airport south of Windhoek, Brigadier Crous requested Cdt Black to send the Super Frelon helicopter, call sign 302, to the accident scene.

All available Police manpower in Windhoek including SAP reservists were also mobilised to proceed to the accident scene to render support. All three cinemas in Windhoek as well as the Windhoek drive inn were contacted to announce on the intercom that all SAP members immediately have to report to the police station. Doctors were also requested to be available to provide medical assistances at the crash site and the local hospitals.

Ten minutes after receiving the request the Super Frelon with Brigadier Crous on board departed to the accident scene, where they arrived 30 minutes after the initial alarm was raised

The Super Frelon circled at the accident site but due to the thick smoke which came from the burning wreckage, the helicopter could not land and proceeded to the JG Strijdom airport to refuel. Three doctors also boarded the Super Frelon which returned to the crash site.

The survivors of the crash were all but one seriously injured and were transported to the Eros Airport, Windhoek for medical treatment by the Super Frelon helicopter. Due to the fact that no night flying facilities were available at the Eros Airport, members of the local Army Commando in Windhoek were called up for duty to assist with the lights of their vehicles, to make it possible for the Super Frelon helicopter to land safely. The only person that survived the disaster without injury was a Thomas Taylor.

The two Alouette lll helicopters and the Super Frelon helicopter returned to the crash site to ferry rescue personnel and equipment to the area. The next two days saw these helicopters being used extensively by the crash investigation team.

The SAAF also gave further support by supplying one of the Lockheed C130 Hercules transport planes to fly the bodies of the crash victims to Jan Smuts International Airport in Johannesburg.

South African authorities refused to confirm reports they also had found an estimated $700,000 worth of diamonds being carried by a Dutch diamond merchant. A special investigating team from Johannesburg combed the wreckage for bags of diamonds reportedly worth $700,000 that were aboard the plane.

The story of Thomas “Tom” Taylor

Thomas “Tom” Taylor, a passenger on flight SA 228, was seated in Seat 1F and survived with minimal injuries and was one of the five survivors of the crash. He is a US citizen, employed by the US Department of State as a courier and was on his way from Johannesburg to Frankfurt, Germany and ultimately heading to Washington, D.C. He earned the nickname “Miracle Man” at the US Department of State,*Diplomatic Security Service (DSS).

Taylor was thrown clear when the plane smashed into the ground. Two farmers who were first to reach the burning wreckage, found Taylor sitting off to one side, mumbling and shaking his head aimlessly hack and forth, “I came out of that plane,’’ he whispered. “I felt a bump and found myself sitting on the ground . . . why . . . why should I be allowed to live?” By late morning Taylor was reported in “very good” condition.

Taylor’s account of the disaster:

“I was reading a book throughout the take off and it felt as if the aircraft was gliding along the ground … a bit rough but I was not aware of it until the lights went out and I was seated upside down. I somehow unfastened the seatbelt and left the plane … then nothing until I was on a stretcher in a helicopter”

Taylor was hospitalized and received treatment. His diplomatic pouch was found in the wreckage and handed back to him. He later returned to the US and resumed his duties. Not much else is publicly known about him post-crash. He lived in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, USA.

* Remark:

“The Diplomatic Security Service (DSS) is responsible for the U.S. Diplomatic Courier Service, which handles sensitive diplomatic materials and cargo worldwide. They’re like the ultimate delivery squad for top-secret

documents”

The aircraft apparently also carried Japanese diplomatic pouches.

Eyewitness Account by former SAP Member stationed in Windhoek: Jan De Waal

Jan de Waal is a former SA police officer

who was stationed in Windhoek at the time the SAA Boeing 707 SA 228 crashed in Windhoek:

On Saturday 20 April 1968 at about 21:00 he was walking back to the SAP barracks in Bahnhof Street, next to the Windhoek Police station after he had visited his girlfriend.

Jan de Waal:

“A police van driven by the sector sergeant on duty stopped next to me and yelled: “Get in!”. And you get in the back of the police van and you didn’t even have time to go and fetch your clothes because a message had arrived about a Boeing that crashed at the airport and the airport is still another 32 kilometers outside Windhoek.

I was a young police officer of 19 years old and joined another eight policemen, you do not really have police experience…you only realise what they told you during the journey…and there were about eight of us in the back of the police van… and you begin talking…and you realise what is going on. Some of the guys had previously dealt with bodies…but for me…for many it was our first experience with bodies….and all of us that were “rounded-up”…I was perchance one of the first to be rounded up…we were all taken on the same trip out to the airport. And they had…at the two drive-in cinemas…at that stage I think there was still only one drive in in Windhoek. The police van stopped at the drive-in and made an announcement over the cinema’s loudspeakers…there had been a Boeing accident and all policemen that might be in the drive-in theatre had to report to the police station immediately.

Let me say that when we came to the scene…now it was…to the east side…about a kilometre or two…the distance from the airport where it crashed..

When we arrived at the crash site to the east of the airport, it was chaos at the scene…itis dry in South West at that stage…it is autumn, the ground is hard and dry.

We saw a furrow…I’d say about a meter (deep)…about 3 or 4 meters in length…a furrow it made in the ground…and the plane must have apparently lifted up again…if that was due to the shock of impact or whatever but it lifted up again…and about 10…15 meters further on there were another two furrows probably made by the two engines either side and the fuselage in the middle

….also about a meter deep…furrows…and then the one wing broke off…the right wing.

The fuselage…it turned and …well basically in the middle…it broke…well more towards the front. Totally broken where it divided in two…

and one engines broke off and was found off to one side in the veld but the wing that broke away must have slided on for about another kilometre into the veld and it burnt out completely…well let me say the next morning there was just molten metal lying there.

Now wonder of wonders…there was one guy…I think there were 5…yes. I think there were 5 that survived… there was one…now I speak under correction…but one died on the way to hospital as well…of the other four three were pretty badly injured…but there was an Englishman…I cannot recall his surname miraculously…he didn’t have a scratch on him…let me say he was a bit disorientated and was wondering about the bushes…we had to catch him…his most serious injury was due to wandering through the bushes… Now you have to think about this…for this chap who has just come out of a Boeing disaster to be put in a helicopter to be transport to hospital…and the chap is fully aware of things…he is awake…that was a bit of a battle…at the end of the day we wrapped him up in a blanket and bound him with belts so that he would…at the very least…not become physical in the helicopter.

The thing that mostly effected every body was the smell at the scene… .The lack of proper light was a big problem…it was in the veld on a farm …the only light you had was the vehicles that were there at the time and each chap had a torch…that was the light. Now if I tell you my own experience…you arrive at the scene…you do not realise what has taken place…you are completely…and then suddenly you see…you see this bunch of…the entire place is scattered…you see parts of people…and a hundred plus scorched bodies…not badly burnt…oddly not one was totally consumed…they were just scorched…just enough for them to swell up… if you think…for example…you go to a body and you make to pick it up…you think you have it but the skin peels away to the wrist…all of them scorched to the point of blistering… And the smell of the scene…I do not know if the smell was caused by the type of fuel that made it worse but the smell of paraffin…It is the same smell that you experience when you are an airport ….it was really…incredible.

Policemen, police reservists, Airport and Windhoek municipal fire brigade people, security and airport people, a big SA Air Force helicopter and two police helicopters …as time passed….through the night .. they became more plentiful… You get a guy and his head is gone…his tonsils and tongue is here…that’s the bodies which you picked up there… The bodies…well let me say not bodies but parts of them… The largest percentage…if I think correctly…of all the bodies we recovered…there was one man that had shoes on…

One of the hostesses…she was apparently still standing with the microphone in her hand…probably busy with announcements or notifications…the wiring of the aircraft caught her here behind the jaw…so that she was hanging on the wiring with the microphone like this in her hand…

A lot of gruesome things…we found body parts in the bushes…and later took them to the ambulance. In that moment you stand there in disbelief. What you see here in front of you is basically impossible…what is in front of you… Let me say…when you get to the aircraft itself…you do not realise…let me say you realise then how huge the thing is…clothes hung in trees…babies’ nappies…it’s… What was heart wrenching were the small children…Oh…mutilated…

broken… There…from young to old…there was not a policeman that did not shed tears that night…or that night and the next day…from hardened guys who reckoned well they’ve been in the force for years…there’s not really anything that can get them down…no…there…there…from stranger to relative…let’s just say there was not a person on the scene that did not cry.

The next day, at the farm gate where you entered the area of the farm where the Boeing crashed, the police erected a police tent. An Engelbrecht guy and I…we had to stay there in the tent for a week because no journalists or anybody else were allowed on the scene. Now that was also not a pleasant experience…you are parked there in the tent both day and night on the scene…and it was the third day I was walking around…well you walked around there every day and looked around…and see what else there is to recover…and strangely everyday you found either another piece of flesh or something …a piece of clothing…and that is when I found this little table cloth…let me say I was walking and I saw it hanging up there like a little flag. Obviously it was full of blood…there were blood marks but naturally my wife thought it best…well you best not store it with blood…it’s 42 years ago …but this is a tablecloth from the Pretoria…it’s…and it’s of immense value to me”

Epilogue

The father of the compiler of this article, Herbert Ernst Witschas, was one of the SAP reservists that was called up to assist at the crash site.

When he returned home late on Sunday morning, we as a family immediately realised that the disaster deeply struck him which was made more intense when you saw his clothes soiled by the soot of the burning wreckage and the smell of it. He just said: “It was terrible, something I had not witnessed in my life before not even during World War II in Eritrea and Abyssinia, 1940-1941”

This was the worst aviation disaster at that time in the history of South African aviation and in South Africa & SWA.

The Helderberg disaster of 28 November 1987, when the Boeing 747 SP Combi, SAA flight SA 295, from Taipei, Taiwan to Johannesburg, crashed into the Indian Ocean, northeast of Plaisance Airport, Mauritius, killing all 159 people aboard, made it the worst aviation disaster to date.

Reference:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/South_African_Airways_Flight_228

https://aviation-safety.net/wikibase/331864

https://www.flightlevel42.co.za/Onthou_SA228_Translation.pdf

Onthou-Remember: kykNET: 2010

Waldo van der Waal: Executive Producer: Plan-C Productions

https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=MT19680422.2.14&e=—–en–20–1–txt-txIN

Madera Tribune, Volume 76, Number 241, 22 April 1968

X #CouriersAt100: go.usa.gov/xnnm3

Book:

Eye in the Sky: A Brief History of the SA Police Service Air Wing: African Aviation Series

Herman Bosman

Freeworld Publications

Pages: 75-77

Wolfgang Witschas is a former member of the South African Police (SAP 1976 – 1981)(Uniform & Detective Branch), a member of the National Intelligence Service (NIS 1981 -1994), National Intelligence Agency (NIA 1995 – 2008), and the State Security Agency (SSA Domestic Branch 2008 – 2016).