THE REASONS BEHIND THE WIDELY PRAISED POLICE HANDLING OF THE 1973 DURBAN STRIKES

by Dr Willem Steenkamp

(Political scientist & retired ambassador, lawyer, and intelligence analyst)

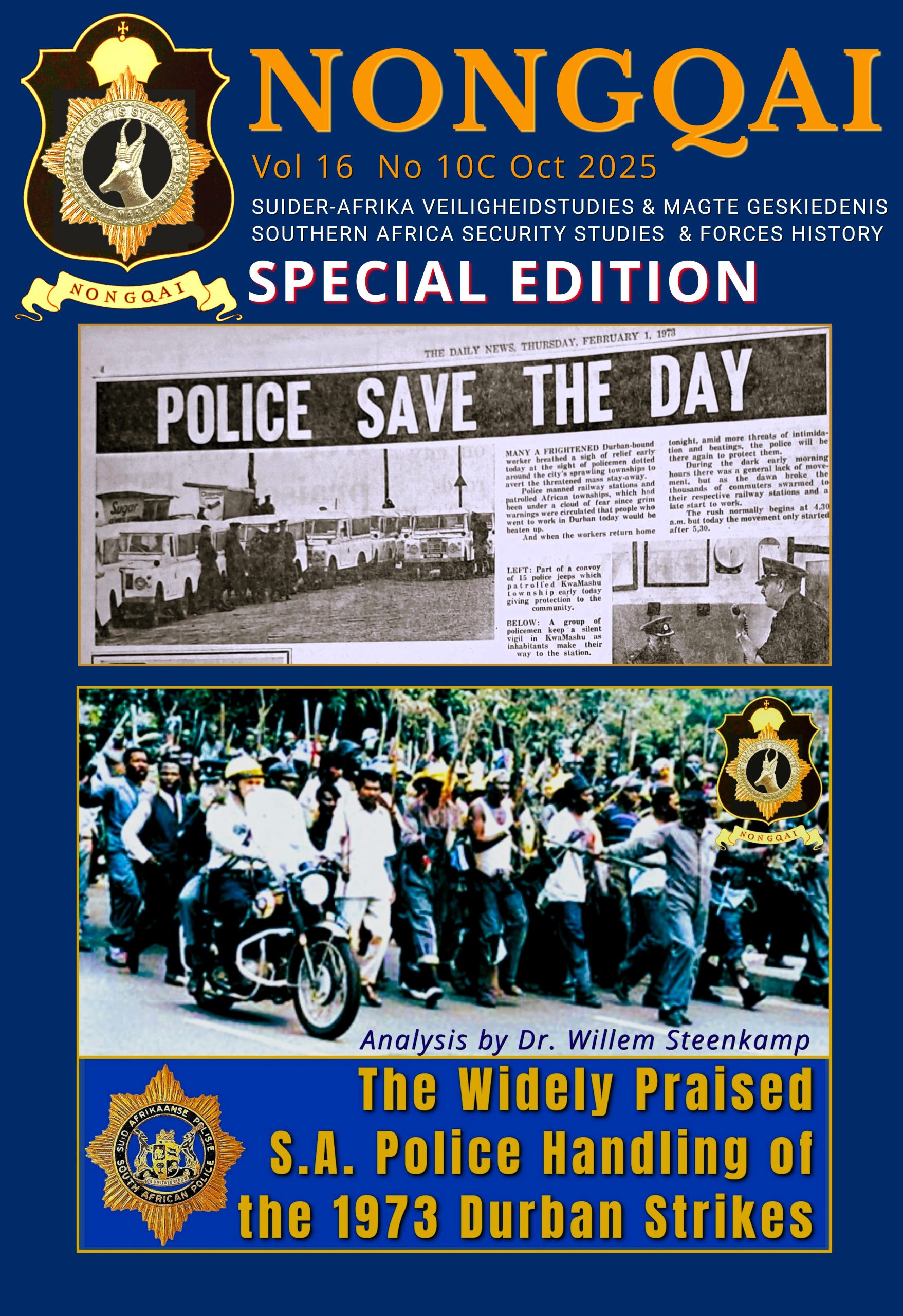

ABSTRACT: The informed, sympathetic, and restrained manner in which the South African Police in Durban handled the massive 1973 labour protests there, was a determining factor in the peaceful and productive resolution of that situation. However, the background to, and determinants of the reasoned thinking that had motivated the widely praised Police handling of the 1973 Durban strikes have as yet not been properly analysed and recorded for posterity.

Many observers and academic researchers (especially on the left of the political spectrum) were seemingly mystified by the insightful, carefully calibrated conduct of the police in Durban. They perceived it to have been “mild” (seemingly to their apparent disappointment?) because it did not correspond to their own fixed negative assumptions about policemen at the time. Much of this stemmed from these observers not understanding (or being unwilling to admit) the true nature and origins of the labour protest on the one hand, as well as – on the other hand – not being willing to credit the police for their intelligence capabilities and situational awareness.

Be that as it may, it is generally agreed that the manner in which the Police chose to respond to the situation was central to its peaceful, positive resolution. More importantly, it was also the catalyst for the then SA Government to appreciate the strategic importance of the labour issue in a national security context, given its potential for paralysing the country’s economy. This led the Government of premier John Vorster to urgently embark upon reforming the labour relations legislation so as to stay ahead of the curve, which steps were key in avoiding that (from 1973 right up to the end of the era of white government in 1994), the revolutionary forces on the Left ever could bring the country to a standstill by means of mass national strike action – not even at the height of the internal conflict during the tumultuous 1980s could they successfully organise a countrywide general strike .

In the 50+ years since the 1973 Durban strikes many actors on the left have, in revisionist manner, attempted to claim parentage to those events as if the SACP/ANC and their then sympathisers had inspired the Durban protests. They have also tried to ascribe the fact that the Police had not responded with brutality, as due to the Police supposedly having been “overwhelmed”.

In this article, the author identifies the real causes that ignited and drove the protests, as well as the key Police commanders (and their strategic motivations and intelligence-based insights), assessing these determinants in terms of the theories of “rational actor” and “political learning”.

The Durban policing successes is also compared to the calamitous consequences of less well led, less reasoned, and less disciplined SA Police actions, such as during the Sharpeville Tragedy, the 1976 Soweto youth unrest and the 2012 Marikana Massacre, thereby illustrating the determinative role of police action in how such mass protest events play out, plus what broader negative image consequences they can lead to for the government of the day.

KEYWORDS: 1973 Durban Strikes; South African Police; SAP Security Branch; Brigadier Theo Bisschoff; Colonel Karools Mouton; Colonel Frans Steenkamp; Sharpeville; Soweto youth unrest; Marikana Massacre.

AUTHOR: Dr Willem Steenkamp

READ TIME: 45 minutes

- THE 1973 DURBAN STRIKES: BALANCING A ONE-SIDE HISTORICAL RECORD THAT IS MARKED BY REVISIONISM, POLITICAL AGENDAS, AND CONFUSION

South Africa has seen much revisionist re-writing of its history since the change of government in 1994 (which, to be honest, is not much different from similar tendencies in the rest of the world, throughout time, when those who won power retro-actively try to re-cast history in a light favourable to themselves…).

In the case of modern South Africa, this has for example happened with regard to the 1960 Sharpeville Tragedy, where nowadays the historic truth is suppressed that the SACP/ANC at the time had vehemently opposed the PAC’s organisation of that protest (to the point of beforehand distributing pamphlets trying to dissuade the black public from participating in those protest actions). Similarly, the fact that the SACP/ANC had had no hand in the Soweto student unrest of 1976 (which was organised by the Black Consciousness Movement), is nowadays ignored as the ANC-led government perennially tries to take ownership of that event.

A further factor which has contributed (in the case of the 1973 Durban labour unrest), to the tendency to portray it as having been part of the SACP/ANC’s “unstoppable march” to eventual power, is that many of those who have since written about the 1973 events were, back then, personally involved in the small fringe of Marxist-leaning activism in white student politics in Durban at that time. Consequently, there is in the public record a one-sided imbalance, due to a preponderance of writing on the subject having originated from this one particular ideological angle, bur also due to a corresponding dearth of writing and analysis looking at those Durban events from the opposite angle – therefore, a textbook case of a “single story” by default dominating the public record.

This has left many who nowadays wish to find out what had actually transpired in Durban in 1973 with a confused picture as to what exactly had happened there, and – even more importantly – WHY it happened in that supposedly unusual manner.

Two examples of this self-serving latter-day revisionism will suffice to illustrate the point. Dave Hemson (who had been a leader among the small activist group of leftist students who had tried very hard to gain influence over the protesting workers at the time) wrote for the 50th commemoration in 2023 that: “The police were armed and widely present; additional militarized police with battle experience in the then Rhodesia were flown in as reinforcements. Some marches were baton charged, others teargassed, some arrested and charged but over time the police were paralyzed by the human wave of strikes and abandoned enforcing the anti-strike laws”. (Review of African Political Economy, June 2023).

Grace Davie of Queens College, City University of New York, wrote: “In the early 1970s, white university students helped change debate about low wages in South Africa by convincing workers to base their claims for higher pay on the Poverty Datum Line (PDL), an academic measure of the cost of living for average urban households. Founding members of the Student Wages Commission reached out to workers through propaganda, overcame workers’ initial suspicions, avoided infiltration by police spies and eventually convinced dockworkers to attend meetings of the Department of Labour’s Wage Board. Through a complex process of translation, statistics became a means of speaking back to the state. By winning media support and persuading workers to appropriate the PDL, the Wages Commissions created a less predictable and more fluid dynamic between employers and employees in the months leading up to the landmark 1973 Durban strikes”. (Journal of Southern African Studies, Volume 33, Number 2, June 2007).

On the other hand, directly after the strikes the Institute for Industrial Education (the brainchild of activist Durban academic Rick Turner, who had inspired his students to set up the Wages Commission) had investigated the labour protests in depth and published a report coordinated by one of those students (Gerhard P. Maré) in 1974, which back then had stated:

“African workers had previously struggled to use the trade union and strike weapons of the industrial proletariat, but had failed, both because of repressive State action and because of certain crucial social factors, in particular, the fact that many of the workers were unskilled labourers and easily replaceable by the large numbers of unemployed. The Durban strikes are different in two important ways.

“Firstly, the State did not intervene in strength. No force was used against strikers. The arrests that were made were of groups of workers marching through the streets who were fined minimal sums, and no violence was used to force workers back to work. Secondly, the strikes were largely successful. The workers did not have their initial demands satisfied, but nearly all of them did gain appreciable wage increases…

“The strikes either came about through some quite complicated underground organisation (of which there is no evidence), or else they came about as a result of a large number of independent decisions by unofficial leaders and influential workers in different factories.”

In the booklet Maré explained the origins of this Social Sciences-based study as follows:

“Foszia Fisher and Karel Tip and other members of the Staff, and the Academic Advisory Panel of the Institute for industrial Education… Lawrence Schlemmer, of the Institute for Social Research at the university of Natal, gave us all manner of advice and assistance. Alec Erwin, of the Department of Economics, and Eddie Webster, of the Department of Sociology contributed many helpful comments on the original manuscript… This study was originally designed and initiated by Richard Turner, of the Department of History and Political Science at the University of Natal, but restrictions placed upon him by the government at the end of February, 1973 made it illegal for him to take any further part in the study, We regret that we are not permitted to associate his name with this publication, Two other participants, Halton Cheadle and David Hemson, have also since been banned and, can, likewise, no longer be associated with this publication.” This “pre-revisionism” study conducted and reported by the then core group of Leftist campus activists themselves, can therefore be seen as a much more truthful account of what had actually transpired in 1973 than the latter-day revisionism highlighted above.

A thread running through most of the academic writing on the 1973 Durban strikes and the role of the Police in relation thereto, is that the restraint shown was supposedly “surprising” and somewhat of a “mystery”.

Julian Brown, for example, wrote in The Durban strikes of 1973: Political identities and the management of protest (Cambridge University Press, 2018) that: “I argue that – somewhat surprisingly – the state and employers did not automatically use violence to repress the strikes in Durban.”

Similarly, Geoffrey Wood of the Department of Sociology at Rhodes University stated in an article entitled “The 1973 Durban Strikes – of Local and National Significance” that: “The state’s reaction was surprisingly muted. Although riot police were flown in from Pretoria and a strong police presence was visible in the townships, almost no violence occurred. Indeed, it seems that police hardly ever interfered in disputes.”

The Wikipedia entry on the 1973 Durban strikes contains the following sub-heading:

“Insufficient Explanations: The Mystery of 1973

The wave of strikes proved to be a puzzle for many: government, the media, unions, and social scientists, among others. What was difficult to explain was the fact that after a prolonged period of union-bashing which was more successful than not, a resurgence would take such a sudden and dramatic form.

While government officials such as the minister of labour and others announced that agitators had orchestrated the entire episode, other government agencies such as the police admitted that they had not detected the presence of specific groupings pulling the strings…

Wikipedia (on role of Police): The police were present throughout the duration of the strikes. However, they rarely intervened and were reportedly told to use only minimum force when required. For the most part, strikers were described as “generally good-natured” and non-violent. … It is noted amongst scholars that if police had intervened, matters would have escalated and become dangerous. Employers and members of parliament insisted that “agitators” were responsible for causing the strikes. Marais Viljoen, the Minister of Labour, blamed the National Union of South African Students (NUSAS), the Black Workers’ Project (BWP) and the Trade Union Council of South Africa for the labour disputes and made reference to how agitators were planning on taking down the State. Despite this, police claimed there to be “no evidence of an organisation behind the strikes.”

Modern-day Artificial Intelligence (AI) bots are also not exactly in accord with each other about the role of the Police in the 1973 Durban labour protest actions, nor on how the strikes unfolded.

Chat GPT states: “The South African Police (SAP) played a significant and complex role during the 1973 Durban Labour Unrest, a major turning point in the history of South Africa’s labour movement… The SAP’s role in the 1973 Durban strikes was one of surveillance, intimidation, and selective repression, but not full-scale violence. Their relatively restrained response marked a shift in how the apartheid state dealt with African labour — partly because the scale of the unrest showed that repression alone was no longer a sustainable solution.”

Taking a different tack, X’s GROK AI gave a much more nuanced reply to the self-same question about the role played by the Police.

GROK AI (X): “The South African Police (SAP) played a significant but restrained role during the 1973 Durban Labour Unrest, a series of strikes involving over 60,000 black workers demanding better wages and working conditions. The strikes, which began on January 9, 1973, at the Coronation Brick and Tile factory and spread across various industries, were illegal under the Native Labour (Settlement of Disputes) Act of 1953, which prohibited black African workers from striking. Despite this, the SAP’s response was notably measured, contributing to the largely peaceful nature of the protests.

“The SAP was quickly mobilized to maintain public order, as the scale of the strikes—eventually involving around 100,000 workers by March—caught the government and employers off guard. The police were present throughout the strikes, but they rarely intervened directly and were instructed to use minimal force. This approach was based on accurate intelligence and situational awareness, which helped prevent the escalation of tensions. For instance, at the Coronation Brick and Tile strike, 1,500 workers marched peacefully, and the police presence did not lead to significant confrontations. Scholars note that had the police adopted a more aggressive stance, the situation could have escalated dangerously.

“The SAP’s professional and judicious handling of the unrest was widely praised in contemporary media. The Natal Witness reported the arrival of SAP units in camouflage gear as “shock troops,” but emphasized their calm and non-repressive conduct. Similarly, the Natal Mercury commended the SAP for its restrained approach, noting that it avoided heavy-handed tactics despite the illegality of the strikes. Only 353 arrests were made by the end of 1973, a relatively low number given the scale of the protests, further highlighting the police’s minimal intervention.

“This restraint was not universal, however. Later in 1973, at the AA Western Deep Levels mine, police violently suppressed a smaller strike, resulting in 12 deaths, indicating that the SAP’s approach varied depending on the context and perceived threat. In Durban, the peaceful nature of the strikes, combined with the SAP’s strategic decision to avoid provocation, allowed workers to negotiate wage increases without significant violence. This contributed to the strikes’ success and laid the groundwork for the resurgence of black trade unionism, eventually leading to the formation of major unions like the Federation of South African Trade Unions (FOSATU) in 1979.

“In summary, the SAP’s role in the 1973 Durban Labour Unrest was primarily one of containment through presence rather than active repression. Their restrained approach, guided by effective intelligence, helped maintain public order while allowing the strikes to proceed largely peacefully, marking a significant moment in South Africa’s labour history.”

As will be shown below, the manner in which the Police managed the 1973 Durban strikes was in fact neither surprising nor a mystery – it actually was a textbook example of what modern Business and Political Science would describe as “Rational Action” (the theory that humans typically will, in reasoned manner, choose the most beneficial course of action open to them) and that the restraint showed was also a consequence of another theory, namely that of “Political Learning” (which postulates that humans learn from past mistakes).

What assessments by left-leaning authors that the Police action was “surprising” and a “mystery” illustrates, is a lack of knowledge about both the true determinants of the unrest as well as about the intelligence capabilities and situational awareness that the Police possessed (plus, an ingrained prejudice on the part of such authors whose default assumptions didn’t allow them to credit the Police with the level of sophisticated insight and empathy that in fact marked the thinking and actions of the Police).

- WHAT ACTUALLY HAPPENED, FOR WHAT REASONS, AND GUIDED BY WHOM?

- BACKGROUND

2.1.1 The Labour Situation at the time

During the first half of the seventies much of Durban’s Black labour force consisted of Zulu-speaking migrant workers from the interior of the province of Natal. They were mostly housed in employer-provided hostel compounds, within which traditional indunas exercised considerable influence. It was also part of the traditional societal fabric of the migrant worker pool that most labourers who worked in a particular industry (and thus residing in a company-associated compound) would hail from the same region and clan in the interior. For example, the workers of Durban’s municipal sanitation department (manning the refuse removal trucks) practically all came from the same clan in Southern Natal, whilst those working the “night cars” in turn came from a neighbouring clan. Speaking the same language, sharing the same culture, and then mostly hailing from the same clans per industry, ensured that the famously effective African “bush telegraph” did its reputation proud during the labour unrest in 1973, with information passing between different hostels, industries, geographical locations and individual workers with lightning speed – also to workers residing in townships outside the hostels.

The migrant workers were mostly unskilled manual labourers, for example working as stevedores on the docks or as porters in the municipal market, who could easily be replaced by employers. Typically, these migrant workers were traditionalist in outlook, and practically all were still firmly part of the social structure into which Zulu males were organised from birth – one could stop at any filling station in the province (as well as in the Zulu-dominated areas beyond) and ask any pump attendant to which Zulu regiment he belonged, and he would unhesitatingly be able to state his affiliation. Thus, the Zulu royal family and the views of the king, his prime minister and indunas carried great weight. Importantly for the events to unfold in 1973, so did the typical Zulu male cultural norms and warrior ethos, which prized manliness, discipline and dignity and which insisted upon respect.

There were industries that required skilled workers, such as machine operators and the like, where trained and experienced workers could not as easily be replaced by employers as they could those essentially rendering merely manual labour. This applied to sectors such as textiles and those requiring licensed drivers for vehicles, for example. These kinds of posts were typically occupied by workers, Black and Indian, who were locally resident on a permanent basis in the townships around Durban – not by migrant labour.

What was the Industrial Relations system in place by law in South Africa in early 1973? At the outbreak of the Durban strikes in January 1973, Black workers did not enjoy the right to unionise, nor to go on strike. The official system then in place made provision for the establishment of sectoral Wages Boards under the auspices of the Department of Labour, which would periodically review and determine minimum wages applicable to different industrial sectors, which determinations the employers (and employees) then had to abide by. However, at that time this system was functioning less than optimally, with long delays between determinations unfortunately being common.

2.1.2 The Political Situation in Natal in 1973

In terms of popular support (or rather, lack thereof) the SACP/ANC found itself at a low point in Natal at the beginning of the 1970s. Its public action campaigns against, for example, the pass laws had attracted few participants. The sabotage attempts by it military wing, MK, had fizzled out (the operatives having been arrested), and in the province the movement was internally divided about the wisdom of resorting to armed struggle, which had been opposed by the former ANC President Chief Albert Luthuli and leading local communists such as Rowley Arenstein. However, small activist cells still existed, particularly in academic circles, with Rick Turner prominent, striving to inspire those among his students who showed leftist leanings to engage in concrete activism.

Given the communist ethos of promoting proletarian revolution among the working class, it was logical that – considering the prior failure of the SACP/ANC’s attempts at mass mobilization and armed struggle – there would be an attempted shift to increased emphasis from their side on prioritising worker-focused action. It was thus evident to activists (and to the State’s intelligence community) that the labour terrain potentially held great strategic importance, since the demographics of the country dictated that the successful mass mobilisation of black workers in the cause of a communist-inspired revolution, could indeed paralyse the country’s economy and bring the white-governed state to a fall.

Again, however, there was at the time no consensus among leftist activists in Durban as to how to go about this. Rick Turner, understanding the reality of migrant worker importance in the equation and comprehending their traditionalist outlook, believed that the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) of the Zulu king’s prime minister, Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi, was an unavoidably necessary tool with which to reach and cultivate these workers. However, more fundamentalist Marxists among the ranks of activists in Durban saw Buthelezi as a reactionary and a threat to the SACP/ANC. As was eventually shown in the 1994 elections, the IFP was indeed the dominant Black political force in the province, especially so among hostel dwellers, and communism as such was anathema to these traditionalist Zulus.

From the IFP side, there was an obvious political incentive for them to be publicly seen as instrumental in achieving the betterment of the wages of their followers and thus the IFP worked hard to facilitate this, but they were simultaneously also aware of the need not to harm the economy through sanctions and unreasonable industrial action, which would in Buthelezi’s view hurt Blacks more than Whites. Nevertheless, at the time of the Durban strikes in 1973 many employers held the erroneous belief that it was Buthelezi who was behind the strikes (he was, in fact, out of the country, on a trip to the USA), thereby illustrating the fact that the then-reigning public perception was that the traditionalist IFP was the main local political force, and not the SACP/ANC.

2.1.3 Anti-government Activist Aspirations at the time

Because the SACP/ANC’s mass mobilization campaigns and armed struggle had failed to gain traction, by the early seventies their focus in the Durban area had indeed shifted to trying to instigate labour activism. This was initially mostly directed at the local textile industry, which at the time employed about a third of all Black industrial workers in Durban and surrounds. What these mostly non-Zulu Leftist activists found, however, is that the workers were not interested in unionisation, nor in communist ideology. Their concern was their wages. Therefore, the angle of approach adopted by the Left was to promote the formation of mutual benefit societies (akin to stokvels and burial societies) instead of unions, and to launch among student activists the Wages Commission, which had as priority their Poverty Datum Line project. This latter strove to exploit the research and data processing capabilities available to students, to determine factually what kind of information to present to the Department of Labour’s Wage Boards, for the purpose of determining sectoral minimum wages (from the political perspective, though, this project would serve the Activist Left as a means with which to conscientize the workers about just how unjust their wages were and to polarize them against the system purportedly exploiting and oppressing them, with a view then to more easily mobilizing these conscientized, polarised workers into action aimed at bringing the system down).

2.1.4 SAP-SB Concerns and Preparations in the run-up to the 1973 Labour Protests

On the part of the Security Branch of the SA Police (SAP-SB) the potential for Marxist activists to target the Black labour force because of its clear potential to be developed into a key strategic tool, was well understood. The SAP-SB, tasked with maintaining a stable environment for economic and constitutional development, thus had four primary goals in the strategic arena of industrial relations:

- Because of Black labour’s strategic importance, to avoid that Marxist activists capture the Black labour corps (for which, above all, good intelligence was needed);

- To avoid that activist organisations achieve substantial standing with Black labour (for which it was necessary to ensure that the white activists not receive any recognition or credit for any improvements in working conditions achieved);

- To facilitate (when tense situations arise that could easily be exploited by activists to foment discontent), that the necessary remedial action be promptly taken by employers and government – the top two such stability-threatening situations being unfairly low wages and a dysfunctional Industrial Relations system (the SAP-SB, from their perspective, therefore saw equally as much need for fair wages to be paid as any activist did, and furthermore understood the essential need for the State to have a functional Industrial Relations system in place);

- The SAP-SB’s last goal was that, in dealing with industrial action by Black workers (and whilst ensuring the maintenance of public safety and protection of property), that the Police take no unnecessary actions that would antagonise workers, create martyrs (and mediatic funeral events) and serve to feed the Activist Left’s very capable propaganda machine – such as had, for example, happened in the case of the Sharpeville Tragedy little more than a decade earlier, leading to untold damage to the image of the Police and the State.

The Police’s actions in the run-up to and during the 1973 Durban strikes (as informed by the local SAP-SB command), were thus not based on knee-jerk reactions but were rationally calculated to serve the State’s best interest – exactly in the manner of “rational action” theory in Economics and Social Sciences, which postulates that human beings are likely to follow courses of action that best serve their fundamental interests. Having learned from the Sharpeville Tragedy, the way in which the Police chose to handle the 1973 Durban Strikes also conforms to modern “political learning” theory, which postulates that humans learn from the consequences of costly past mistakes.

As we shall see, the conduct of the Police in Durban is thus not such a “mystery” as pretended in some circles, nor was it an aberration. Instead, it is entirely logically explicable as having been both rational and the product of learning – this insight is, of course, predicated on the condition that those proffering judgements do not simply assume that the police were irredeemably dumb brutes, incapable of learning and of rational action…

The SAP-SB country-wide had been well aware of the strategic importance of the labour relations field, as well as of increasing efforts at the beginning of the 1970s by SACP/ANC orientated campus activists to target this potentially mighty weapon. The 1968 student unrest in Europe, particularly in Paris, had also made clear that university campuses could become hotbeds of revolutionary activism. For those reasons the SAP-SB (not to mention the Bureau for State Security, which then actually had primary responsibility for intelligence gathering about student activism) had made a concerted effort to set up reliable intelligence-gathering networks on every campus. Serving SAP-SB officers (but undeclared as such) enrolled as students, whilst other officers openly studying on campus served as official liaison between the SAP-SB and university administrations.

In the case of the University of Natal, to my knowledge the SAP-SB had had at least seven of its officers deployed there as enrolled students at the start of the seventies. One such bona fide SAP-SB student at Howard College and who eventually graduated, eventually going on to a Master’s degree, was then-lieutenant Hennie Heymans (today NONGQAI’s editor) who had at that time been designated by the then SAP-SB CO in Durban, Col Frans Steenkamp, as the official liaison between the SAP-SB and the Natal University Durban’s administration.

The identities of the other (undeclared) SAP-SB officers who were enrolled at the University of Natal in the run-up to the 1973 Durban Strikes have not become public knowledge and I will continue to respect that – but lest I’m suspected of making this up, I can mention that I personally know that one of them had resided in Room E.69 of the William O’Brien Residence for a time…

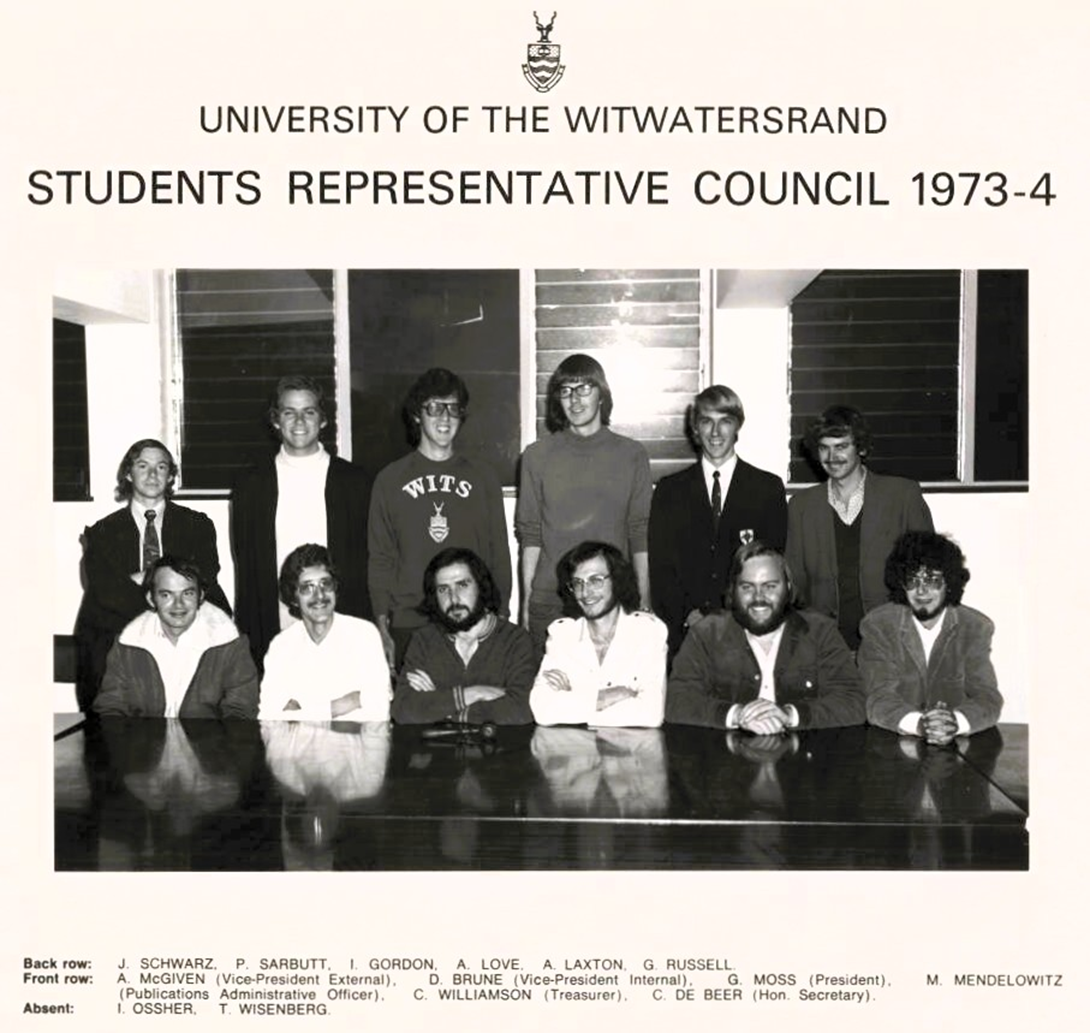

The depth and breadth of this kind of SAP-SB campus penetration can be judged by the intelligence presence on the Student Representative Council of Witwatersrand University in 1973, in the case of which the names of some of those officers involved have since emerged into the public domain.

On the photo below it can be seen that the two vice-presidents, as well as the treasurer of the council, were in fact intelligence officers (Arthur McGiven, Derek Brune and Craig Williamson) with their colleague Karl Edwards playing a leading role as well on the Wits campus. These are only the State intelligence operatives whose true roles have since become public knowledge and does not include sources and agents cultivated and managed by them, nor the ones who have to this day remained un-identified…

It should also be considered that, in the specific case of the University of Natal, the student body and faculty in general were quite conservative. As Bill Guest wrote in STELLA AURORAE: THE HISTORY OF A SOUTH AFRICAN UNIVERSITY: “For the most part the white student body as a whole was much more conservative than liberal in character, there being constant wrangling over whether to maintain a central affiliation to NUSAS”.

Up to 1965 the vice-chancellor (rector) of Natal University had been Prof EG (Ernie) Malherbe, who had been head of South Africa’s wartime intelligence during WW2, and many lecturers also had served in intelligence structures prior to turning to academia. Malherbe was strongly conservative about key issues, such as being against the admission of non-white undergraduate students. He was succeeded by Prof Owen Horwood, who served as rector from 1965 to 1970 and then became a government cabinet minister.

Horwood, whose wife was a sister of Rhodesian prime minister Ian Smith, was succeeded by the British surgeon Prof Francis E. Stock who was serving as rector when the 1973 Durban labour protests erupted. Bill Guest wrote of Stock (who was an establishment figure who, before coming to Durban, had been commodore of the Royal Hong Kong Yacht Club and who received a CBE from the late queen at the end of his term as Natal University rector) that Stock: “…is also shown up for his overly cautious political stance and for his opposition to the admission of black undergraduate students to whites-only universities.”

Thus, whilst there were activists such as Dr Rick Turner among the faculty, the university as a whole and particularly its top administration was conservative and were cooperative with the SAP-SB, maintaining formal liaison channels with it. Grace Davie’s earlier-quoted statement that the Durban Student Wages Commission “avoided infiltration by police spies” is thus mere wishful thinking on her part…

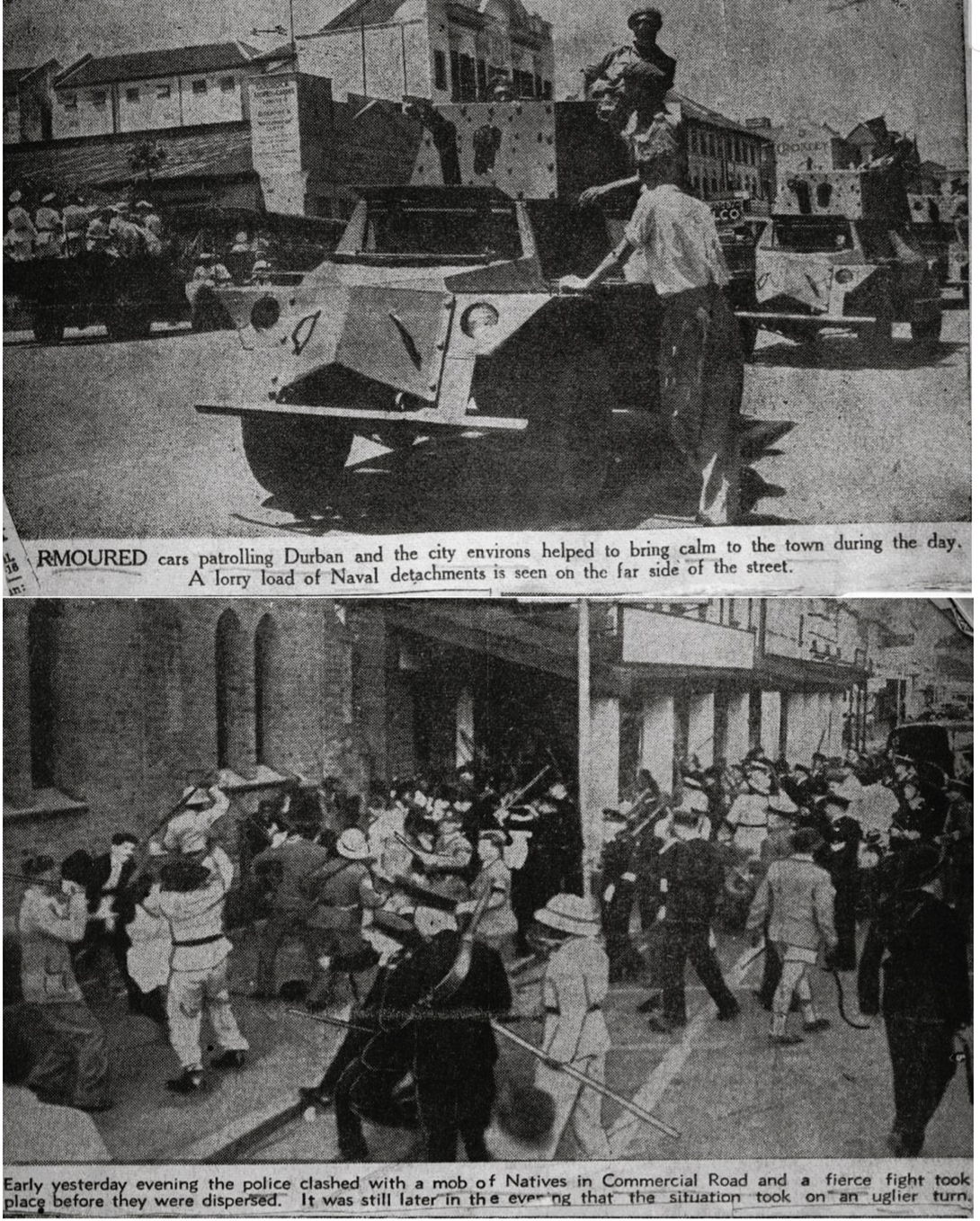

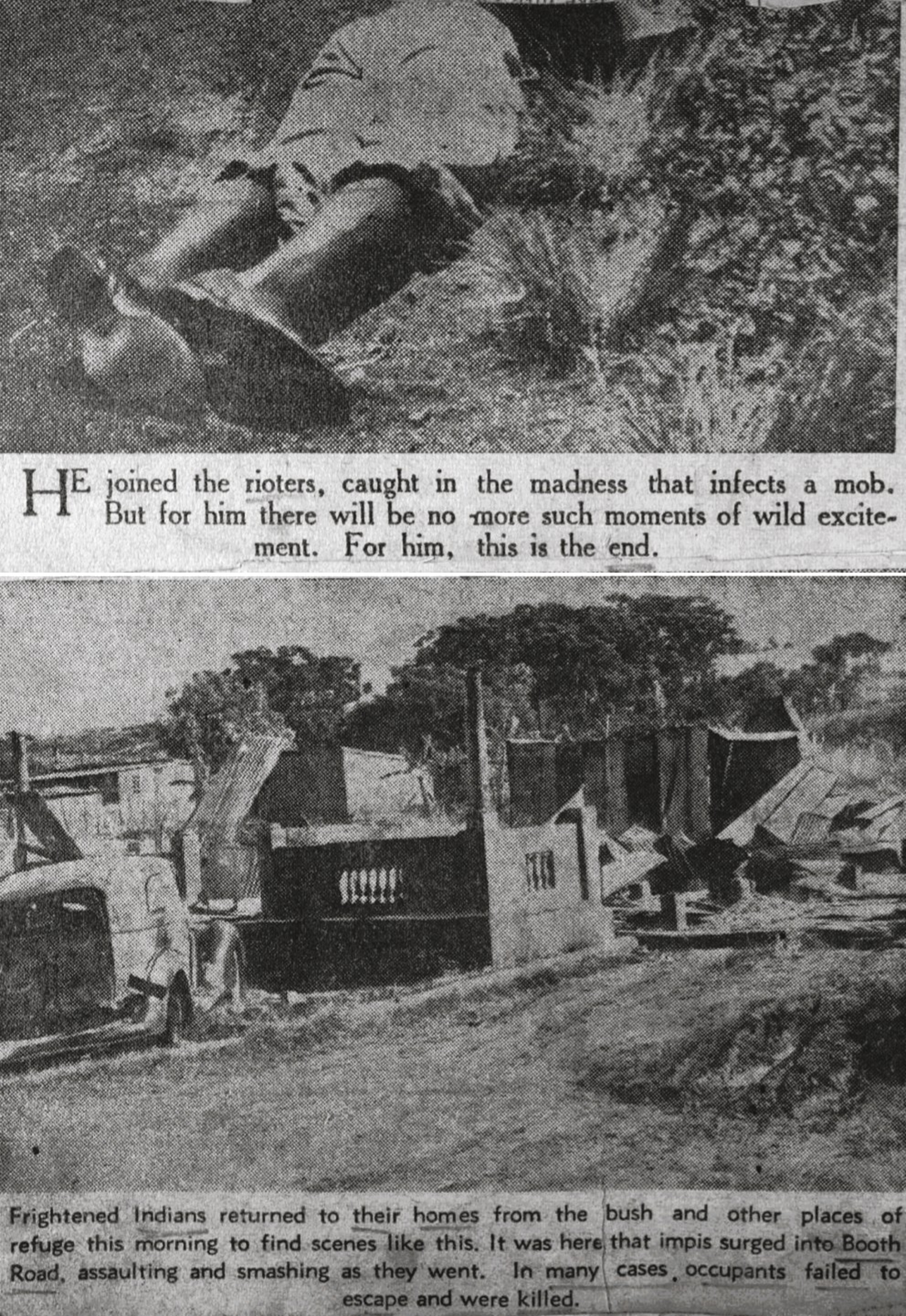

A very pertinent concern of the local Police stemmed from their institutional memory of the combative male Zulu culture, the public order consequences of which had been dramatically experienced in the region as recently as 1949 and 1960. The Police command was very much aware of and fully understood the powder-keg nature of discontent boiling among proud Zulu men who felt disrespected and exploited, knowing how it had exploded into mayhem during the 1949 Durban anti-Indian Pogrom and the 1960 Cato Manor riots.

On 13 January 1949 an Indian shop-owner had assaulted a Zulu youngster. News of this had spread rapidly via the bush telegraph and ignited a pent-up wave of anger amongst the Zulu population against Indians in general, fed by a sense of being disrespected and exploited by them. Six days of carnage followed, leaving a total of 142 people dead and a further 1,087 injured. A total of 247 houses, 58 shops and one factory were completely destroyed and more than one thousand houses, over six hundred shops and two factories were damaged.

What the local Police in 1973 knew had to be avoided above anything else, was a repeat of such a violent outburst of pent-up anger and resentment.

The press clippings below illustrate what the history of 1949 had demonstrated to the Police about how destructively Zulu anger could explode, and thus the need for carefully considered and appropriately calibrated action.

The Police’s awareness of what mob psychosis could lead to was reenforced by the 1960 riots in Cato Manor (then a shanty suburb of Durban) during which nine policemen on an illicit liquor patrol were murdered by an incensed mob, when a Shebeen Queen (i.e., owner of an unlicensed township speak-easy selling home brews) riled them up by falsely accusing the policemen of having assaulted her and disrespected her dignity.

(Credit: Historic Images)

The tragedy that befell their police colleagues at Cato Manor was to play an important role some two months later at Sharpeville, when a crowd of some twenty thousand who had surrounded the isolated police compound there and who were pressing in, taunted the trapped officers that the same fate as at Cato Manor was in stall for them…

Suffice it to say, the Durban police commanders in 1973 were very much aware of how volatile mob psychosis could be, when proud traditionalist Zulu men rightfully felt aggrieved about disrespect and exploitation. The officers in charge well understood that the situation wasn’t at heart a Eurocentric ideological contest about capitalism versus Marxism, but a much more culturally driven and thus very potent anger rooted in traditional values and self-esteem, fed by the practical realities of blatant exploitation and bureaucratic inefficiency.

Above all, the police commanders understood that it would be largely in their hands, whether a peaceful and just solution could be arrived at, or a repeat of 1949 and 1960 would be ignited – which would play directly into the hands of the leftist activists circling the fray to seize upon any such opportunity…

2.1.5 The Size and Mission of the SA Police Force and its Security Branch in 1973

According to UN data, when viewed globally the average number of policemen per thousand of the population is three officers; in Argentina, for example, it is 7.98/1000; in France 4.22; Italy 4.56; Greece 5.07; the Netherlands 2.95; and in the New South Africa it is 3.5).

So, in the “Apartheid Police State”, what was the number of policemen that the SAP had at its disposal, per thousand of the population? If we take 1970 as a basis (when South Africa consisted of the present Republic plus modern-day Namibia), then the South African ratio of policemen per thousand of the population was only 1.379 per thousand. The only other countries on earth with figures anywhere near as low as these that I could find are Haiti and Lesotho, and then Finland (none of which can in any way be compared to South Africa). Thus, it is easy to prove that South Africa during the seventies, when it was frequently described as a “police state”, was in fact one that was hugely deficient in the number of police it maintained…

In addition to the already substantial population of the RSA plus SWA/Namibia who had to be “protected and served” (as per the SAP’s motto), it must also be remembered how enormously vast the extent of territory was that had to be policed by the SAP in those years – at that time it was the 13th largest territory on earth, larger than the territory of all the following European countries combined: Spain + Portugal + France + Italy + Belgium + Netherlands + Germany + Luxembourg + Switzerland + the Czech Republic!

The national borders that had to be guarded were 6,434km long – 2.5 times the distance between London and Moscow. The coastline extended for 4,912 kilometres…

The mission statement adopted by the SAP was: “We undertake, impartially and with respect for the laws and norms of society, to protect the interests of the country and everyone therein against any criminal violation, through efficient service rendered in an accountable manner.”

The Security Branch of the SA Police (initially known as the “Special Branch”) had been founded prior to the Second World War. Its function was to investigate political activity conducted outside the legal framework provided by the constitution (for example, through political actors employing violence such as physical intimidation, sabotage, and terror to promote political ends), as well as crimes aimed at undermining the security of the state, such as espionage and treason. Upon having investigated such alleged crimes, the SAP-SB had to prepare dockets of evidence for the consideration of the attorneys-general in charge of prosecutions, who would then present such cases to court for adjudication. At no time in its history did the SAP-SB exceed 3,000 men.

During is initial years, when South Africa found itself at war with Nazi Germany, the SAP-SB was focused upon investigating radical right-wing activism that supported Nazism and/or undermined the country’s war effort. After WW2, with the advent of the Cold War, the focus shifted to countering communism, which ideology had been outlawed in South Africa (as it had been in places like Australia, as well). The era was dominated by the Cold War communist threat to the West, and in parallel saw the advent of rapid decolonisation, which in Africa gave rise to increasing demands by the indigenous populations for political rights (which the National Party government that came to power in South Africa in 1948 was unwilling to concede within a unitary state). The resultant conflict led many in Black ranks to see their only hope as being allied with the USSR and conducting an armed struggle aimed at establishing a Marxist people’s republic. This found expression in the alliance between the SACP and ANC, and the formation of MK as its armed wing, which immediately launched a sabotage campaign and which actively planned guerilla warfare against the white state.

What motivated SAP-SB members (as still first and foremost policemen) was not any notion of going out on behalf of government to impose by force the ideology of the day such as Apartheid, but rather to protect the population they were sworn to serve against what they saw as a very real existential threat, namely the imposition of a Marxist people’s republic by means of a revolution, instigated extra-legally by local communists and their allies serving as proxies for the USSR.

As reflected in the segments quoted earlier, the SAP and its SB had been generally portrayed as brutish killers and torturers. However, the statistics prove that, between 1960 and 1990, only 67 people died in SAP-SB detention from all causes, the vast bulk of which were natural – only a handful of cases had caused suspicion. For context, this figure of 67 needs to be compared to:

- 474 Australian Aboriginals who died in police custody there, during a similar 30-year period.

- The 214 prisoners who in the year 2019 alone had died in the custody of the new S.A. Police Service.

- The “approximately 900” MK members who, according to the TRC, perished abroad under the care of the SACP/ANC during the conduct of their “armed struggle”.

- The 11,000 deaths in custody in the state of Texas over the past 15 years. (Texas has about half of SA’s population)

- The 350 people killed by British Security Forces during the “Troubles” in Northern Ireland (from a total population of only 1.5 million, i.e., 1/30th of that of the RSA, or

- the 50,000 deaths, 30,000 “disappearances” and 400,000 detentions by South American security forces (with training and technical assistance from the USA) during the so-called “Dirty War” waged against the Left there, during the Cold War.

(Even a single death in custody is, of course, regrettable. Morally speaking, the aim here is not to point the finger at others in a “yes-but” way, like the pot calling the kettle black – the purpose is simply to provide background which may help readers comprehend why the 1973 Durban strikes were handled by the Police in the reasoned and humane way that they undeniably were).

A telling insight into how the SAB-SB officers saw themselves and their world can be had from the emblem that they themselves had designed for an own distinguishing necktie (see photo). This wasn’t something intended to be heraldically registered as an official coat-of-arms, but more like an own club emblem. Nevertheless, its symbolism is significant.

Instead of using typical police symbols such as batons or handcuffs, they chose a chess piece – the knight. Signifying that, in their minds, they were engaged in an intellectual contest that resembled a game of chess. The choice of the knight invokes notions of chivalry and is also rooted in the fact that the knight is the most nimble, agile piece on the board – capable of jumping in behind enemy lines – and not dependent just on straight-line brute force. The other element of the design is a lodestar above: following the Light and staying on course, not straying from the straight and narrow…

2.2 THE KEY POLICE COMMANDERS WHO MANAGED THE POLICE RESPONSE

Even though the local Durban police clearly formed part of a national command structure which laid down policy and goals (as ultimately received from their minister and government-of-the-day) it is evident that the local commanding officers on the front line – each with their own personalities, life experiences and outlook – had played a key role in ensuring that the forces at their disposal were disciplined and well directed, so as to achieve the strategic outcomes desired.

Three officers were of particular importance – the divisional commissioner for Port Natal division (i.e., Durban and coast), Brigadier TM “Theo” Bischoff, his second-in-command Colonel HA “Karools” Mouton (who was the operational commander of the uniformed men on the streets), and the divisional CO of the SAP-SB for Port Natal, Colonel FMA “Frans” Steenkamp.

2.2.1 Brigadier TM (Theo) Bisschoff – Divisional Commissioner Port Natal

Brigadier Theo Bisschoff had many years of experience in Durban by the time that the 1973 labour unrest surged to the surface. He had originally been transferred to the Durban-South police district from Harrismith, where he was to become the district commandant while holding the rank of Major. Over time Bisschoff gained various promotions, up to brigadier (nowadays known as brigadier general), which is the rank he held in 1973 as then the Divisional Commissioner for the entire Port Natal division.

I knew Brigadier Bisschoff through his love for tennis – he captained the Durban police men’s team (my mother captained the women’s team). Although myself just a little boy at the time, I remember him as being well-respected as man and as commanding officer. Strict but fair, with human empathy, he could maintain discipline whilst also retaining the loyalty and respect of those serving under him. He encouraged the young policemen to study further, for example, by facilitating for them to enrol at Natal University. He was an elder in his church and took his faith and its values seriously.

Theo Bisschoff was a “no nonsense” officer but was also endowed with empathy and common sense, as well as sound moral values – during the 1973 Durban strikes Brigadier Bischoff was quoted by the media as telling journalists that: “The police have nothing whatsoever against people demanding higher wages – provided they do not break the law“. He also gave strict instructions that minimum force was to be used at all times (i.e., if and when any force at all was objectively required in order, as last resort, to ensure public safety and to protect property, it had to be of absolute minimum nature – otherwise, the police had to maintain a strictly hands-off posture).

Theo Bisschoff eventually retired from the Police with the rank of major-general.

2.2.2 Colonel HA (Karools) Mouton – Operational Head of Uniformed Forces

Hendrik Albertus Mouton, who became known as “Karools” in police circles, was born on 10 June 1927 in the Karoo hamlet of Brandvlei, the only son of a poor and struggling small farmer. His nickname Karools was a reference to his hardy Karoo youth. For the Mouton family, every day was a challenge, having to deal with grinding poverty. The situation was aggravated when his father died when he was but a little boy.

As the district commander in East London in the 1960s Karools Mouton was outraged by the low wages paid to black farm workers. On more than one occasion he warned farming associations that crime on farms was the result of the low wages for workers and said that he personally would have resorted to crime if he was one of them. Farmers, to prevent crime, had to improve the treatment of their workers.

Later, after having been transferred to Durban, he told a factory owner (who had insisted that the police must use force against strikers) that he would not allow his constables to be stoned by workers who do not receive proper wages.

Karools Mouton became known as a strict disciplinarian, setting the highest standards of performance and behaviour for himself and those under his command. This included fitness demands. As a young man, he was an above average amateur boxer and would remain active in sport for his entire career. He played his last rugby game in 1971 at the age of 44. He took early retirement from the Police in 1982, at age 55, then holding the rank of brigadier.

(Information provided to Nongqai by Brigadier Mouton’s son, Prof. FA Mouton, a Professor of History at Unisa where he teaches modern South African history).

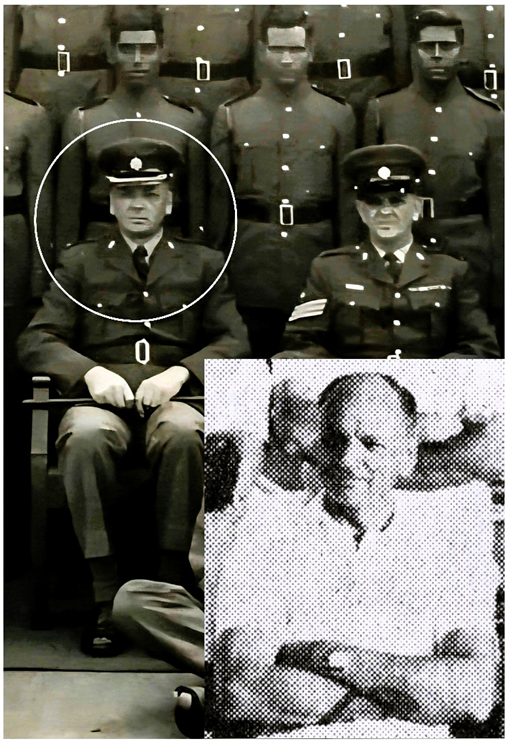

2.2.3 Colonel FMA (Frans) Steenkamp – Divisional CO, SAP-SB Port Natal

A photo of Colonel (later Major-General) Frans Steenkamp taken in the early 1970s

Whereas the Uniformed Branch of the SA Police was locally under command of Port Natal divisional commissioner Theo Bisschoff and Karools Mouton and had responsibility for public order policing, the responsibility for intelligence-gathering, the frontline assessment there-of and for providing strategic input to local and national command structures (up to and including the government of then Premier John Vorster) fell to the separate Security Branch of the Police, of which the Port Natal division was in 1973 commanded by the then 43-year old Colonel Frans Steenkamp – my father.

Frans Steenkamp’s part of the Steenkamp clan also hailed from the Karoo, farming between Sutherland and Calvinia. There Frans’s father, my Oupa Willem, grew up in the home of his uncle, the famed free-thinking “Oudok” WP Steenkamp (independent member of parliament, medical doctor and doctor in Theology, known fondly as the “Lion of the North-West”), after my Oupa Willem’s parents both had died while he was still a young boy. Having been left orphaned, my Oupa had, as young adult, to make his own way in life, with little financial means – and that, during the Great Depression.

Frans himself was born on 4 April 1929 and grew up in Eshowe in the heart of Zululand, where my Oupa Willem had found employment as a government cattle inspector. Frans thus learnt to fluently speak idiomatic isiZulu and became articulately tri-lingual, having inherited the Steenkamp flair for speaking and writing. Frans Steenkamp came to thoroughly know Zulu tradition and culture, before his parents moved to Durban during his high school years (which coincided with WW2). At Durban’s Port Natal Afrikaans high school, he was a star pupil, but he opted to leave school in Standard 9 to join the Police Force in May 1946 (fudging his age to qualify) because of the financial hardship his parents endured at the time. He would later matriculate through home study, gaining five distinctions.

During his wartime high school years in Durban an incident occurred that left an indelible mark upon the young Frans Steenkamp. On a given Sunday, he and his father (who was dressed in military uniform) had attended a church service, but – because of the uniform – they were publicly humiliated and expelled by the hard-right dominee. Frans Steenkamp thus abhorred “Super Afrikaners” and their secret organisation, the Afrikaner-Broederbond, which he never was willing to join.

After completing his initial training in Pretoria and a short stint as constable in Newcastle and Dannhauser in Northern Natal (where he met my mother, who was of Afrikaans-Irish farming stock), Frans Steenkamp was posted as a young detective to Durban. He quickly made name for himself by solving the Joy Aiken/Van Buuren murder case (which had gripped the public and media in the mid-fifties) doing so in record time, after it had stagnated under the detectives that had preceded him. When the SACP/ANC started their sabotage campaign in the early sixties, Frans was drafted to the Security Branch of the SA Police (SAP-SB), where he would rapidly rise through the ranks. By the time of the 1973 labour unrest broke out, he was the divisional commanding officer for Port Natal (meaning: Durban, its surrounds, and the coastal areas north and south of it, up to the respective borders).

As SAP-SB officer Frans Steenkamp had made a point of getting to know, personally, the key personalities in the local politics of his area of jurisdiction, doing so across the ideological spectrum – because he wanted to understand them and their reasoning. This ranged from the traditionalist Zulu leadership such as Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi, to the ANC leader Chief Albert Luthuli, with whom he visited at his residence in Groutville on the Natal North Coast, some 70km north of Durban, for long conversations (Chief Luthuli had in his lifetime not shied away from publicly praising the police in Natal for their tradition of restrained action, and had stated to the media that the police in Natal were “different” to the police in the rest of the country). An early indication of the reasoned strategic thinking of the Port Natal SAP-SB was when the government had agreed to make available to Chief Luthuli (then president of the ANC) a passport so that he could go and receive the Nobel Peace Prize that had been awarded to him in the tense year of 1960 – a step by the authorities that had then also been seen as “surprising”…

When the 1973 labour unrest arose, Frans Steenkamp thus had not only known Zulu culture very well, but he also knew the Durban metropolitan region inside-out, going back to his high school days and through having been stationed there in different capacities for practically the entirety of his police career up to that time.

As SAP-SB divisional commander for Port Natal he enjoyed the personal confidence of his own commanders in Pretoria (the division had been the first in the country to identify and arrest a returned foreign-trained SACP/ANC operative, through excellent counter-intelligence work resulting from maintaining an extensive network of cooperative “eyes and ears”). Frans Steenkamp was also personally know to, and trusted by then Prime Minister John Vorster, who had maintained a close interest in the SAP-SB due to having been minister of police; this was enhanced by the fact that Botha House (the official vacation residence of South African prime ministers on the Natal South Coast) fell within the area of jurisdiction of the Port Natal division, so that it was Col Steenkamp and his men who provided close security to the Vorster family when they vacationed there.

We will shortly review the conduct of, and positions taken by the Port Natal SAP-SB during the chain of labour protests in Durban during January and February 1973. However, it is useful – for a better understanding of Frans Steenkamp’s attitude and approach to security policing – to look briefly also at his later career, because the manner in which he acted and advised in 1973 is not so “surprising” anymore, when we consider how he had consistently approached the country’s challenges also in later years.

Widely read on politics and theory, Frans Steenkamp in April 1977 drafted a circular for his staff in which his deep understanding of the true nature of South Africa’s internal conflict can be seen, namely that it was essentially political, thus psychologically aimed, with a primary role being played by propaganda. This understanding had i.a. helped him analyse, comprehend and then deal efficiently with the 1973 protests. One can see this in the introductory part of his standing order, in which he reminded his men: “During the past few years, the Security Branch has been systematically criticized and discredited in a targeted and well-planned propaganda campaign conducted over a wide field. This of course forms a very important part of the overall attack against the State and the country as a whole. This psychological warfare should not be underestimated and is in no way subordinate to any of the other areas in which the fight against us is being waged, such as the terrorist threat, economic undermining, etc….

We must absolutely ensure in all our actions that as little as possible negative connotation can be attached to our conduct, and preferably none at all. We must restore and expand our image in the eyes of the people. If we do not succeed in this, we ourselves will be responsible for infinite and possibly irreversible damage to our country. The field in which we must do this is wide and covers our every action – on and off duty.

“Interrogations: Assign a suspect to two interrogators and they alone must interrogate him until they reach checkmate with him.

“Only the investigator / s in charge of the investigation may interrogate the suspect. More damage has been done than good by well-meaning colleagues who enter an interrogation in untimely manner.

“Avoid the so-called “team interrogation” where interrogators are replaced. There are more disadvantages than advantages: no rapport is established between interrogator and suspect, interrogators contradict each other and so on. The lengthy interrogation undermines the interrogators and their objectives more than it does the suspect; the chances that the astute interrogator will properly utilize his intelligence and ingenuity towards the suspect are less.

“Act in a civilized but firm manner towards the suspect, thus will you gain and retain his respect.

“Always remember you are a policeman, not a politician; you are investigating a criminal case where the country’s laws have been transgressed and it is not your job or responsibility to defend the right or wrong of the laws.

“Think, think and plan constantly. Our enemies are waging this battle against us with their heads and we must fight them in the same way. It is the safest, most effective and most lasting in its long-term effect. A mental, psychological victory evokes respect; A physical, violent victory brings with it a lasting and growing hatred, resistance and desire for revenge, in any way possible. His respect for you is lost and your respect for yourself is damaged as well.”

Frans Steenkamp’s non-doctrinaire attitude towards the white party-politics of the time speaks from a tearoom joke he had made in the run-up to a general election, and which Brig Heymans fondly recalls: He said that if the Nats won, then he would retain the name Frans, but if the (mostly English-speaking) UP opposition won, then he would become Frank, and if the far-right HNP won he would become Franz…

In later years Frans Steenkamp would become the commanding general of the SAP-SB nationally, during the early eighties. He was known for his opposition to the “all means justified” approach that became synonymous with the “total onslaught” outlook under PW Botha, as well as for his insistence upon scrupulously respecting the rule of law. This led to many conflicts between himself and the military-dominated securocrat establishment under PW Botha. One such incident is illuminating – it revolved around the arrest in the USA of then-commodore Dieter Gerhardt of the SA Navy who was exposed as a Soviet spy; when Gerhardt was flown back to South Africa under FBI escort, Frans Steenkamp resisted efforts by the powers-that-be to have the GRU spy conveniently “disappear” (which they had wanted to do to avoid exposing the SADF to the embarrassment of a very public criminal court case). Steenkamp declared that Gerhardt indeed was a traitor but insisted that he nevertheless was entitled to a fair trial – therefore, General Steenkamp sent some of his most senior officers to receive Gerhardt directly from the FBI on the plane and take him to a secure facility for safekeeping.

Because Frans Steenkamp could never personally identify with the PW Botha securocrats and the “total onslaught” approach of that era, he opted to take early retirement in 1984, when he reached 55. During a farewell dinner for him the then minister of police, Louis le Grange, told those in attendance that Frans Steenkamp was the only general ever to have told him to his face in a meeting: “Minister, nou praat jy sommer k@k” (Minister, nou you are talking plain shit). Frans Steenkamp was not afraid to speak truth to power – that free-thinking, rebellious Steenkamp streak personified also by his uncle Oudok….

In February 1987, having returned to active service in a consultant capacity due to the then rapidly deteriorating security situation in the country, General Steenkamp authored a study in which he urged the government to urgently engage in inclusive negotiations to find a political solution to the country’s political challenges. He explicitly warned that the Police would not be able to maintain internal stability into perpetuity and cautioned that it was wrong to see a communist influence in everything – stating that black political aspirations were in essence nationalistic, like that of the Afrikaner. Knowing the system under PW Botha and realising that this memorandum would likely be suppressed, he classified it as being only confidential, and then personally took it to opinion leaders outside the securocrat ambit such as Prof Johan Heyns of the Dutch Reformed Church, to help them understand what the security situation in the country was really like at that time…

Frans Steenkamp was the only SAP-SB general who had been national commanding officer of the Police Security Branch, who was never summoned by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to appear before it. Neither did he apply for amnesty – insisting that he had never done or ordered anything that he needed to seek amnesty for.

Similarities between Mouton and Steenkamp: It is interesting to reflect upon the similarities in the stories of Mouton and Steenkamp, because I do believe that their life experiences and formation as human beings did have a strong bearing upon how they understood the 1973 Durban strikes, and thus their approach to the policing thereof.

Both had themselves known dire poverty in their own childhoods during the Great Depression, the 2nd World War, and into its aftermath. They thus had a natural understanding of and sympathy with workers struggling under hunger wages.

In the case of both Karools and Frans, the poverty of their respective families had caused them not to be able to pursue academic studies and to instead join the Police for the sake of financial survival. Both, nevertheless, then had sons who obtained doctorates and who held high positions professionally. Prof FA Mouton became professor of History at Unisa. I myself qualified as a practicing attorney in addition to obtaining a doctorate in Political Science, and served as senior intelligence analyst, as former head of the diplomatic academy and then, at age 38, as the New South Africa’s first ambassador to formerly antagonistic “Black” Africa.

Furthermore, both Karools Mouton and Frans Steenkamp opted to take early retirement at age 55, in the early eighties during the reign of PW Botha and the securocrats…

Knowing now the key personalities and their professional trajectories on the local police side, let’s examine the roll-out of the 1973 Durban labour protests.

2.3 HOW THE 1973 DURBAN STRIKES UNFOLDED

2.3.1. The Start, at Coronation Brick and Tile

(Author’s Note: When the troubled labour relations at Coronation Brick and Tile – also then simmering at many other industries in the area – started boiling towards the surface in January 1973, I was back home with my parents for the long summer holidays, having just completed my first year of university studies in Bloemfontein, studying Law and Political Science. Filled with the typical inquisitiveness of a young student, the events that were unfolding were of course of great interest to me, since they directly related to my own fields of study and because their significant national import was very obvious. I therefore devoured all the local newspapers, all of which my father was officially subscribed to, and which thus were available in our house. More importantly, I could discuss the evolving situation with him first-hand over dinner every evening, since it did not involve state secrets or classified operations. I thus had direct insight into how my father had assessed the true facts and the strategic considerations at play).

Because of the nature of their industry, Coronation Brick and Tile (CB&T) required large numbers of manual labourers. Thus, they had established hostel compounds so that these workers (some 2,000 in total) could be recruited from the interior of Natal as migrant labour.

The last local Wage Board minimum wage determination for this sector had been published in 1967. In the six years since then, inflation had been eating away at the value of their salaries, which was exacerbated in the months leading up to the protests by especially a steep increase in transport costs. Discontent had thus already begun to emerge at CB&T early in 1972, to the extent that the then Zulu king, Goodwill Zwelithini kaBhekuzulu became involved in trying to improve matters and came to personally address the workers (the particular group of workers at CB&T had noticeably close ties to the Zulu royal family, with a certain Nathaniel Zulu having been elected by them as their spokesman and Prince Sithela Zulu having been designated by the King as mediator when the protests eventually broke out in January 1973).

There is no doubt, therefore, that the migrant workers at CB&T were traditionalists aligned with the likes of the IFP, and not with radical leftist activism.

A new Wages Board hearing had indeed been held early in 1972, but due to the essential dysfunctionality of that system, no new determination had yet been published when January 1973 came around. (The President of the Durban Chamber of Commerce was later to directly blame the strikes on the “incredible” slowness of the local Wage Board machinery).

The SAP-SB had been following the evolving situation at CB&T closely as it became more tense in the weeks prior to the protests finally erupting. What had become apparent was that the workers at the company were of the belief that, after the Royal mediation the year before, promises of salary increases that had been made by management, were – almost a year on – not being kept. The prevailing sentiment was that they were being disrespected by management, who were treating them like children, not like the proud Zulu men that they were.

At that time CB&T had an acting general manager who was inclined to take a hard line – on the 8th of January 1972, the day before the protests finally erupted, the company circulated a leaflet among workers promising harsh disciplinary action against any disruptors and averring that the discontent was due to “communist agitators”.

It was this leaflet, and particularly the allegation that workers were allowing themselves to be influenced by communists, that triggered the next day’s protest action. The allegations were angrily rejected by the workers – as one of them stated to the Daily News newspaper on the 9th of January: “We would not have gone on strike if this notice had not called us ‘Communists’ ” (DN, 9/1/73).

At 3am on the 9th of January 1973 a call had gone through all the CB&T hostels on the “bush telegraph” for the workers to stage a protest meeting on the main compound’s football field, which call was adhered to by every one of the labour force, also from the company’s outlaying depots. They were marching as Zulu warriors with their traditional weapons, singing ”filumuntu ufesadikiza”, yhe title literally meaning: “Someone is annoying” and the content idiomatically signifying that “Man may be dead but his spirit still lives on”, reflecting their anger at the fact that they felt themselves being disrespected as men, in addition to feeling that they were being cheated out of promised salary increases.

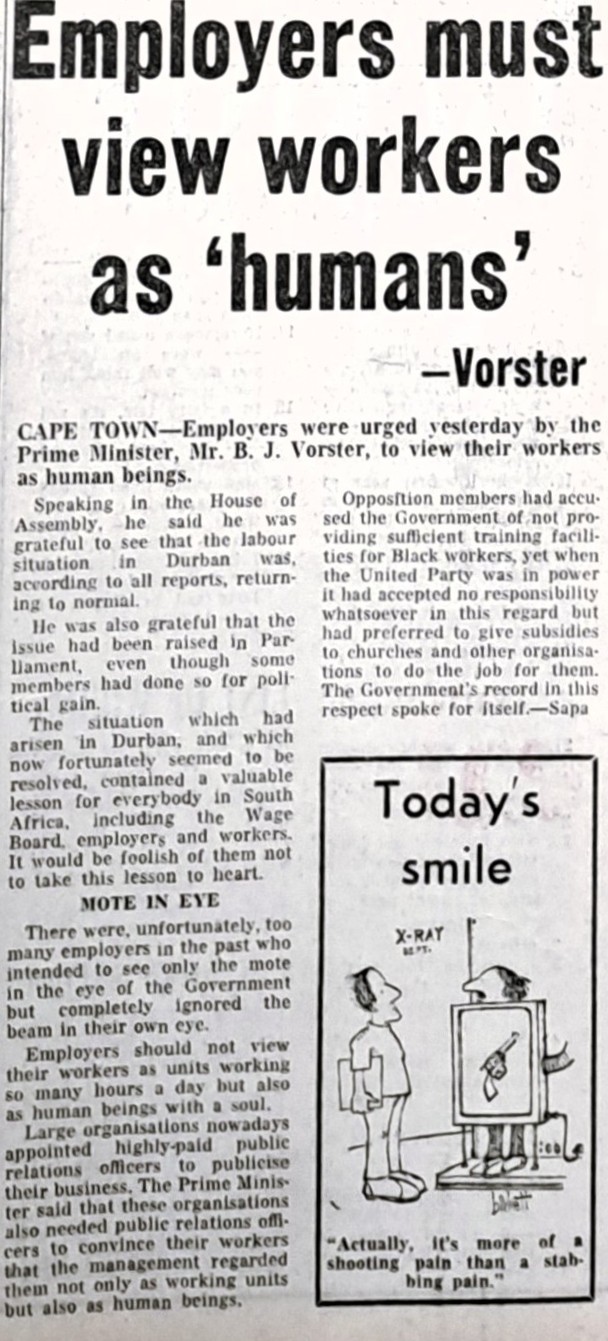

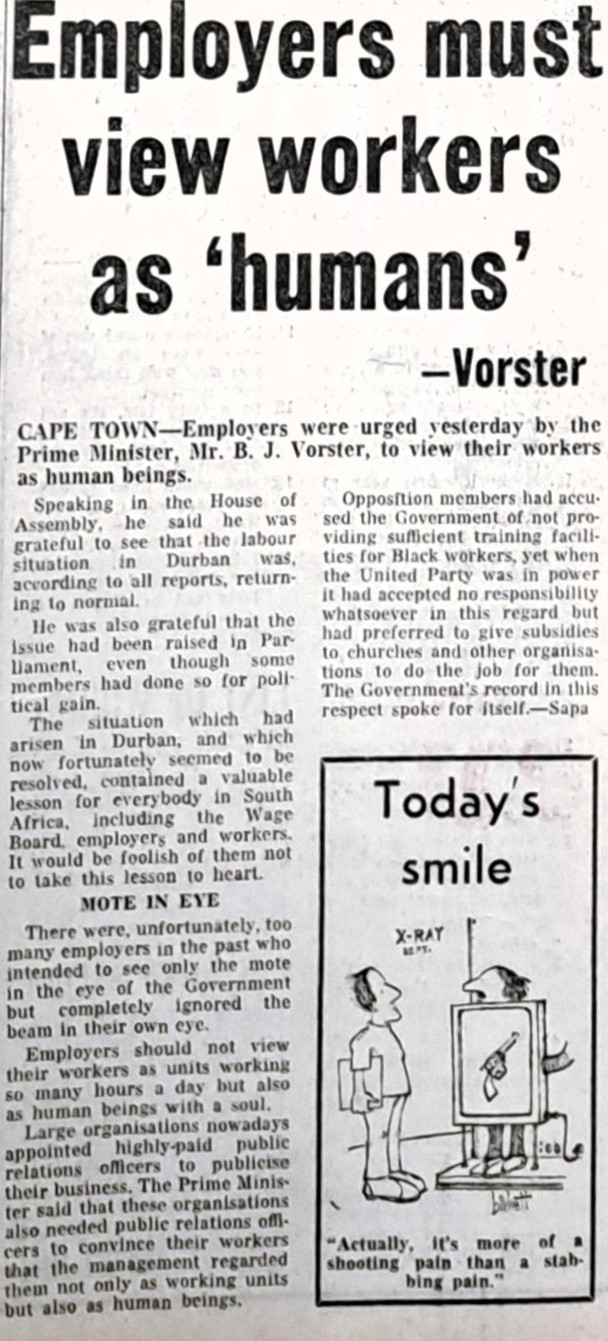

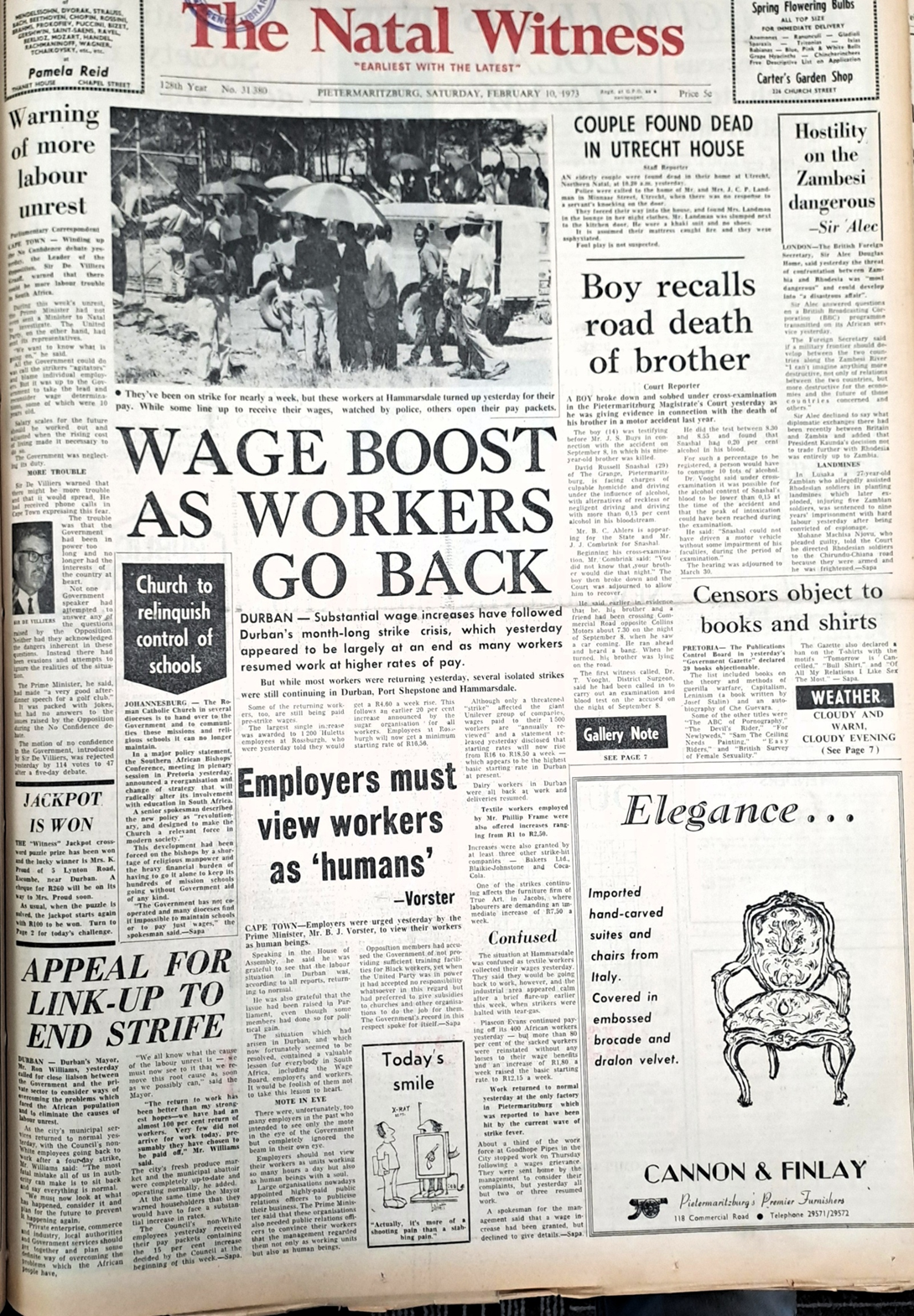

It is noteworthy that Gerhard Maré had chosen as sub-title for the 1974 IIE study on the protests: “Human Beings with Souls”, reflecting the reality that the protests had, in addition to the central matter of salaries, been motivated by human dignity-related issues and not by ideological motivation (what was not mentioned by Maré, was that this sub-title was actually a direct quote from then Prime Minister BJ Vorster’s address to parliament on 9 February 1973 about the labour discontent – see photo below – as quoted by the Natal Witness in their article headlined – “Employers must view workers as ‘Humans’”, with the newspaper then continuing with a fuller quote of Vorster having said: “Employers should not view their workers as units working so many hours a day but also as human beings with a soul”).

The SAP-SB understood perfectly well what the root causes of the CB&T workers’ anger were (it should be noted that the CB&T workers had been adamant that they were not striking but were in fact protesting). The SAP-SB understood that there were three main causes: that the unfair wages were to blame, plus the general treatment that the workers were being subjected to (treatment in sharp dissonance with their own cultural norms and sense of self), as well as being due to the structural problems plaguing the then official industrial relations mechanisms. The SAP-SB also knew that no outside leftist agitation had played any role whatsoever – despite the employers and the Department of Labour’s officials plus their then Minister (Mr Marais Viljoen) immediately claiming instigation by agitators as a self-excusing ploy to try and shift blame away from themselves.

The SAP-SB also understood full well the potential for the situation to degenerate into a deadly disaster at a human level, with national and international political repercussions (by feeding the propaganda machine), if mis-handled. From this understanding logically flowed the decisions of the Police Command to adopt a hands-off posture, avoiding the confrontation that the use of force inevitably would bring. The Police knew that the only true solution to the situation was for the employers in the region to begin paying fair wages, and thus the “rational action” on the part of the government and Police was to leave it up to the workers and employers themselves to resolve their differences, whilst putting pressure on the employers to accede to what was just and necessary (and stopping them from trying to hide behind the fig leaf of non-existent communist agitators).

What the local SAP-SB also did was to immediately make use of their excellent relationships with local Zulu traditional and political leaders, requesting them to engage with the workers to ensure discipline and order, with as reasoning that the Police would not need intervene forcibly if there was no threat to life and limb, or to property.

The Police were not alone in their perception that the wages then being paid to Black workers in the region were unfair – in a scientific survey among whites conducted by Maré and the IIE, 90% of local whites (English and Afrikaans, in the same proportions) felt that workers were being paid too little.

Comprehending the potential for the situation to evolve extremely negatively, the situationally aware local SAP-SB were also concerned that it shouldn’t come to present an opportunity for the Activist Left to exploit the grievances to ingratiate themselves with the workers – and thus not to give these activists any undue status by ascribing the protests to their supposed (but in fact non-existent) instigation. All of the foregoing considerations informed the core of the messaging that the Port Natal SAP-SB reported up their national chain of command, through the Security HQ in Wachthuis, Pretoria, up to the Prime Minister, as well as locally to the divisional commissioner of the Uniformed Branch, Brig Theo Bisschoff.

In brief, the Port Natal SAP-SB had excellent intelligence readily to hand and possessed superb situational awareness, which they quickly and cogently transmitted to the highest national levels of decision-making. Col Steenkamp also was willing and capable of standing his ground. Despite the Labour Minister (the party heavyweight Marais Viljoen) initially publicly asserting that Leftist agitation was behind the protests, Frans Steenkamp repeatedly confirmed on the record to the media that the SAP-SB had seen no sign of outside agitation nor organisation.

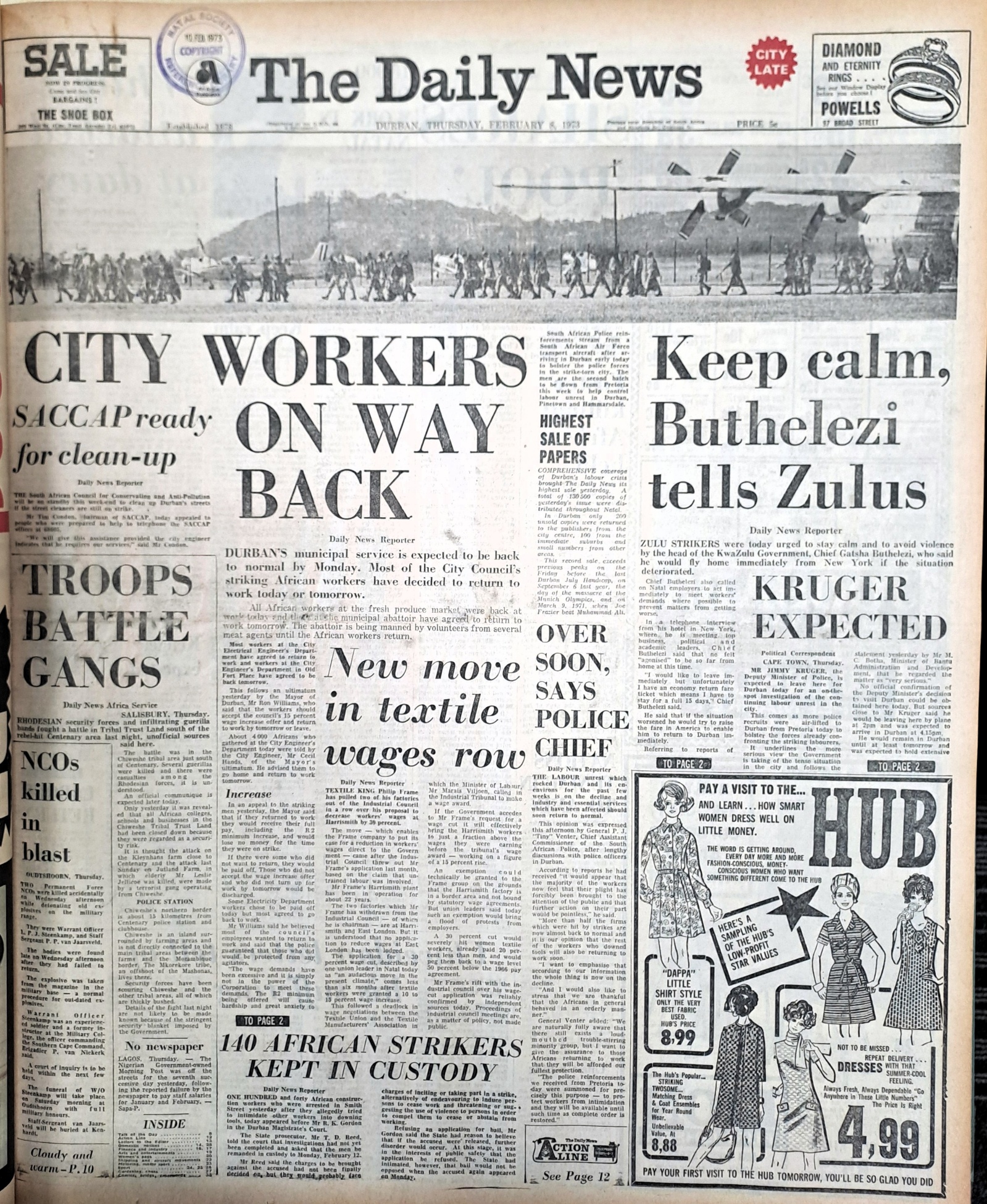

On the 10th of January the Zulu king personally came to address the CB&T workers. He subsequently appointed his counsellor Prince Sithela Zulu, as mediator. In fact, the CB&T protest was settled relatively quickly, when the company’s Board of Directors realised that the State was not going to intervene on their behalf to quash the unrest (with the Government actually applying pressure on them to raise wages).

It took about a week for the CB&T company and the workers to reach a settlement on a new salary scale and work thereafter resumed as normal.

Zulu king, Goodwill Zwelithini kaBhekuzulu, addressing the protesting BC&T workers

For his part Prince Gatsha Buthelezi (as then the chief minister of the KwaZulu administration) attacked low wages and called for full trade union right for Black workers. He strongly criticised employers who threatened dismissals: ”Firing people in these circumstances points to the insecurity of black people in general. This kind of insecurity is dangerous because blacks might ultimately ask themselves: what have we to lose?”.

2.3.2 The Protests quickly spread, copycat-style, thanks to the bush telegraph

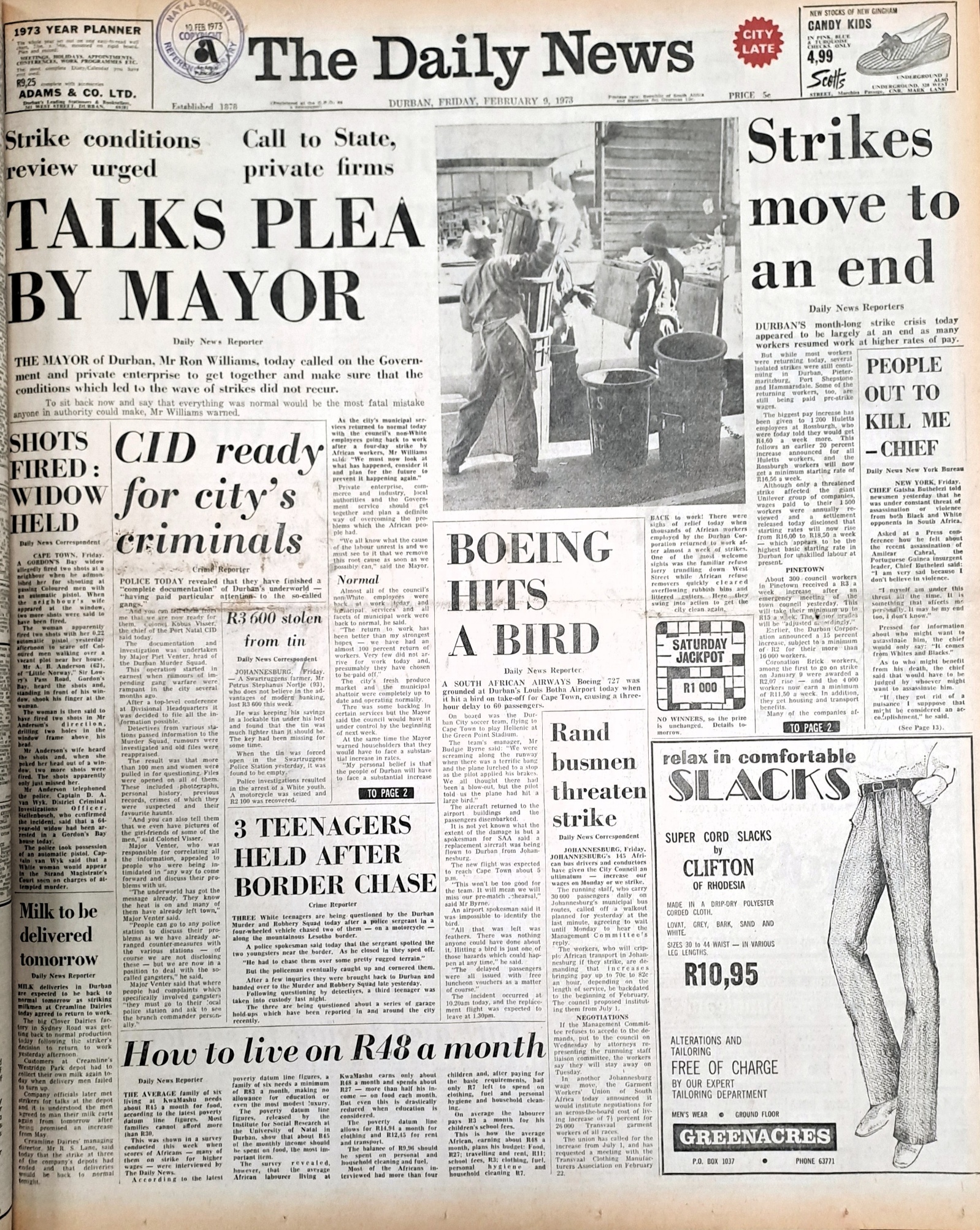

As could be expected, the very efficient African bush telegraph quickly spread news about the CB&T protest actions to the compounds of other industries and throughout the surrounding Black townships. The formal media of all stripes also realised the newsworthiness of what was beginning to happen in Durban and reported extensively on the situation. Thus, was set in motion a chain of copycat labour protests leading into full-blown strikes in certain sectors, which was to last till early March of 1973 (although most of these were resolved quickly, so that calm had essentially returned by early February).

On the 10th of January, 70 black African workers at the transport company A.J. Keeler stopped working for 45 minutes. They demanded a R2 wage increase. This was rejected by management on the grounds that workers were already receiving above the legal minimum wage.

On the following day, the 11th of January, the next company to be affected was T.W. Becket & Co where some 150 black African workers stopped working and demanded a R3 per week raise in wages. This was refused by the company which threatened to fire the strikers and then sought (unsuccessfully) the support of the Police and Dept of Labour. The stand-off between the Becket management and workers continued till 25 January. On that day, the striking workers had again rejected an offer from management, who were then obliged to agree to the R3 wage increase demanded, together with an undertaking that there would be no reprisals against those who participated in the strike.

During the first week of strikes six companies were hit, mostly in the marine and transport sectors. While the Beckett strike was ongoing, Zulu ship painters at several firms in the docks such as J.H. Akitt and Co and James Brown and Hamer also went on strike. On Monday the 26th of January about 200 convoy drivers at the Motorvia firm in Pinetown outside Durban went on strike and organised a picket.

By the end of January the number of companies affected had grown to twenty-nine. The Frame Group, also known as Consolidated Textile Mills (CTM), which operated multiple textile factories across greater Durban and was owned by the local industrialist Philip Frame, was the worst affected. On Thursday, the 25th of January, workers at the Frametex factory in New Germany went on strike. On the 26th the strike action spread to four other textile mills owned by the Frame Group. The strike continued for a couple of days and involved between 6,000 and 7,000 Zulu and Indian workers. By the end of January, every factory of the Frame Group in Natal had been affected by the strikes, bringing production to a complete standstill.

Whereas many industrialists in Durban and surrounds had quickly realised which way the wind was blowing and had then pre-emptively raised salaries to head off industrial action at their sites, Philip Frame was initially hard-headed and point-blank refused to raise salaries. However (jumping ahead of the chronology a bit) as his group’s activities were paralysed and as he came to understand that the State was not going to intervene on his behalf (and as he developed a working relationship with Col Steenkamp, whose judgement he came to trust) in the end Philip Frame did agree to a pay increase that the workers accepted and the strikes at CTM eventually were also duly settled, effectively bringing the significant strikes to an end already by mid-February.

As indicated earlier, Prime Minister Vorster himself had also made a public call for employers to pay fair wages and treat workers as human beings with souls, not merely as units of production.

However, by the beginning of February matters were still balanced on a knife’s edge, with the strike action beginning to impact essential services.

2.3.3. Key sectors were becoming affected

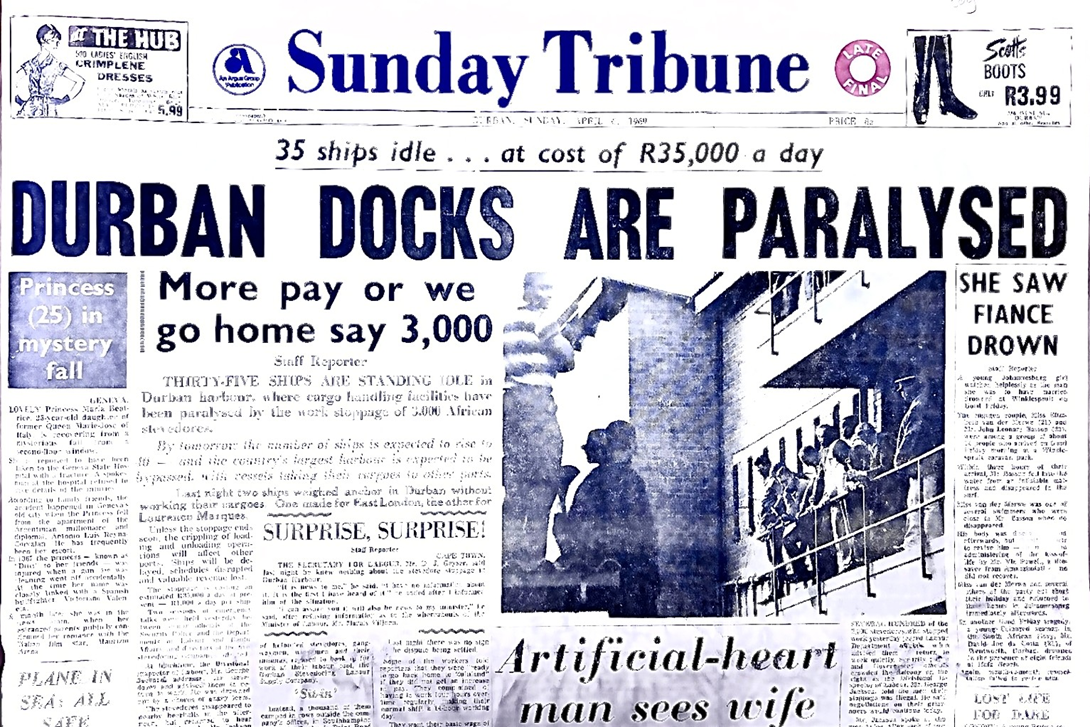

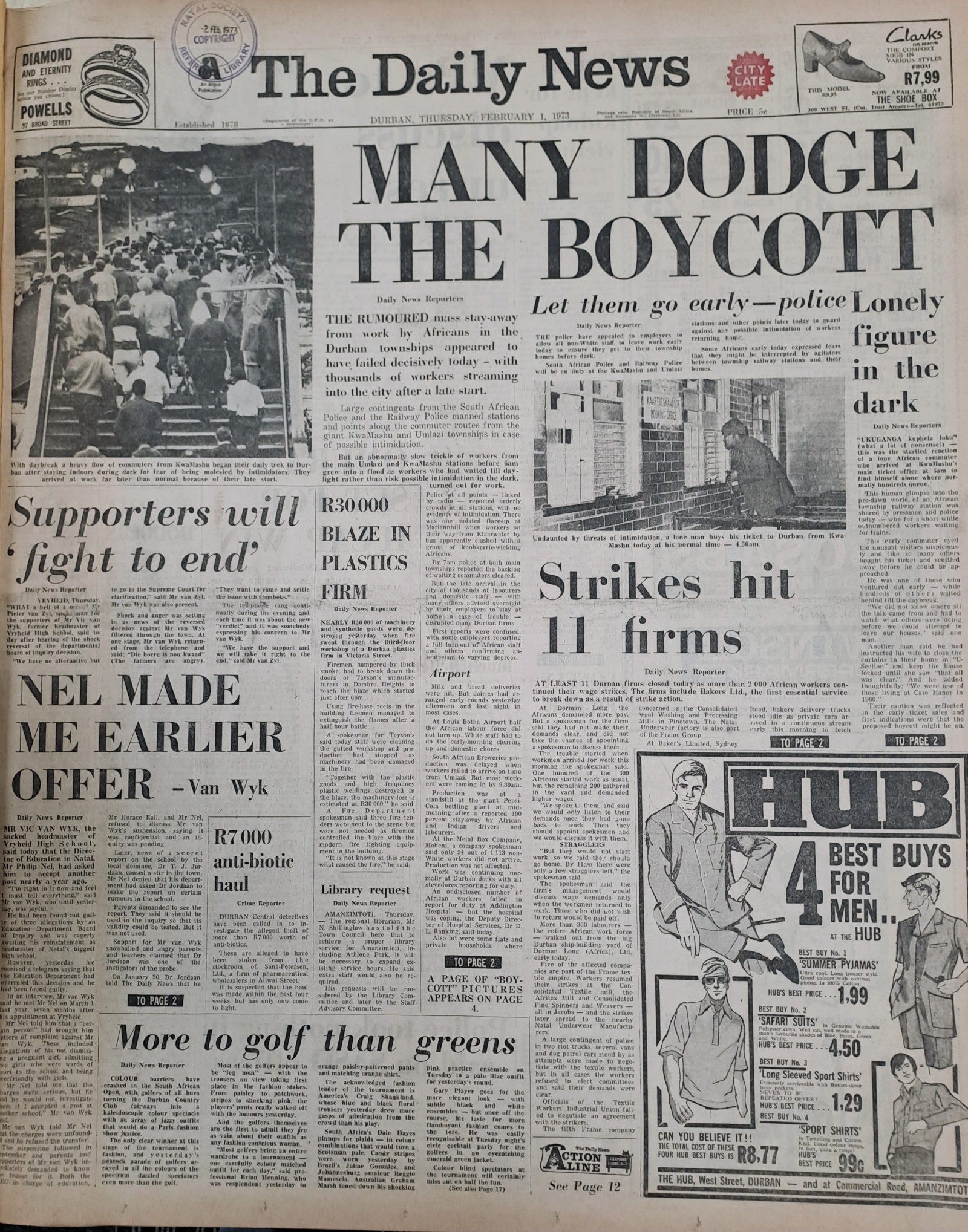

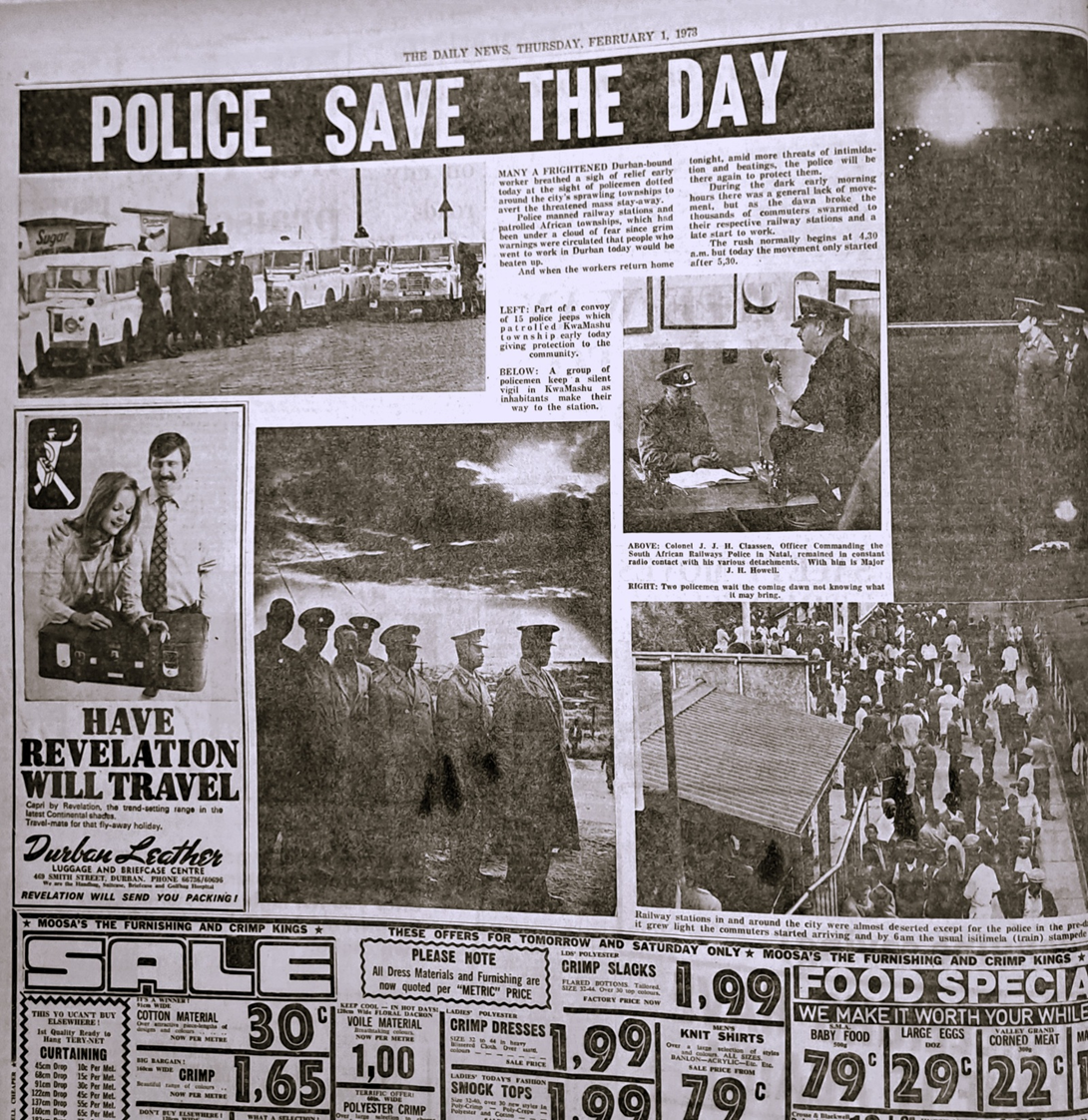

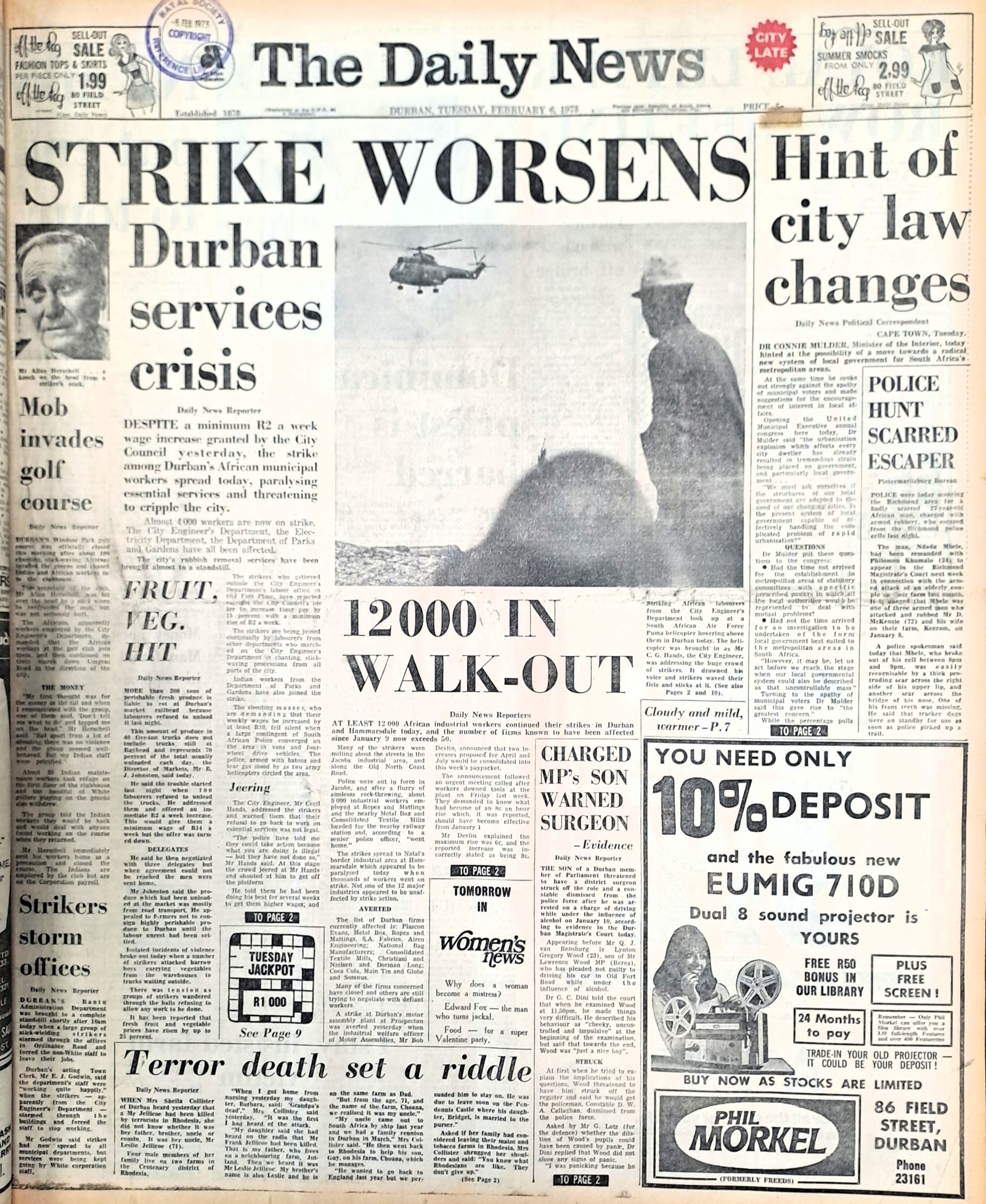

On the 1st of February 1973 there were tense moments because of rumours that strikers would attempt to prevent workers from boarding trains to and from work. The SAP as well as Railways Police ensured that an adequate and highly visible precautionary presence was maintained at railway stations, also requesting employers to allow workers to return home well before dark. As a result, the day passed without mishap (as can be seen in the following press cuttings)

In early February the strikes started to affect sectors of key strategic importance, holding the potential for considerable disruption of essential public services.

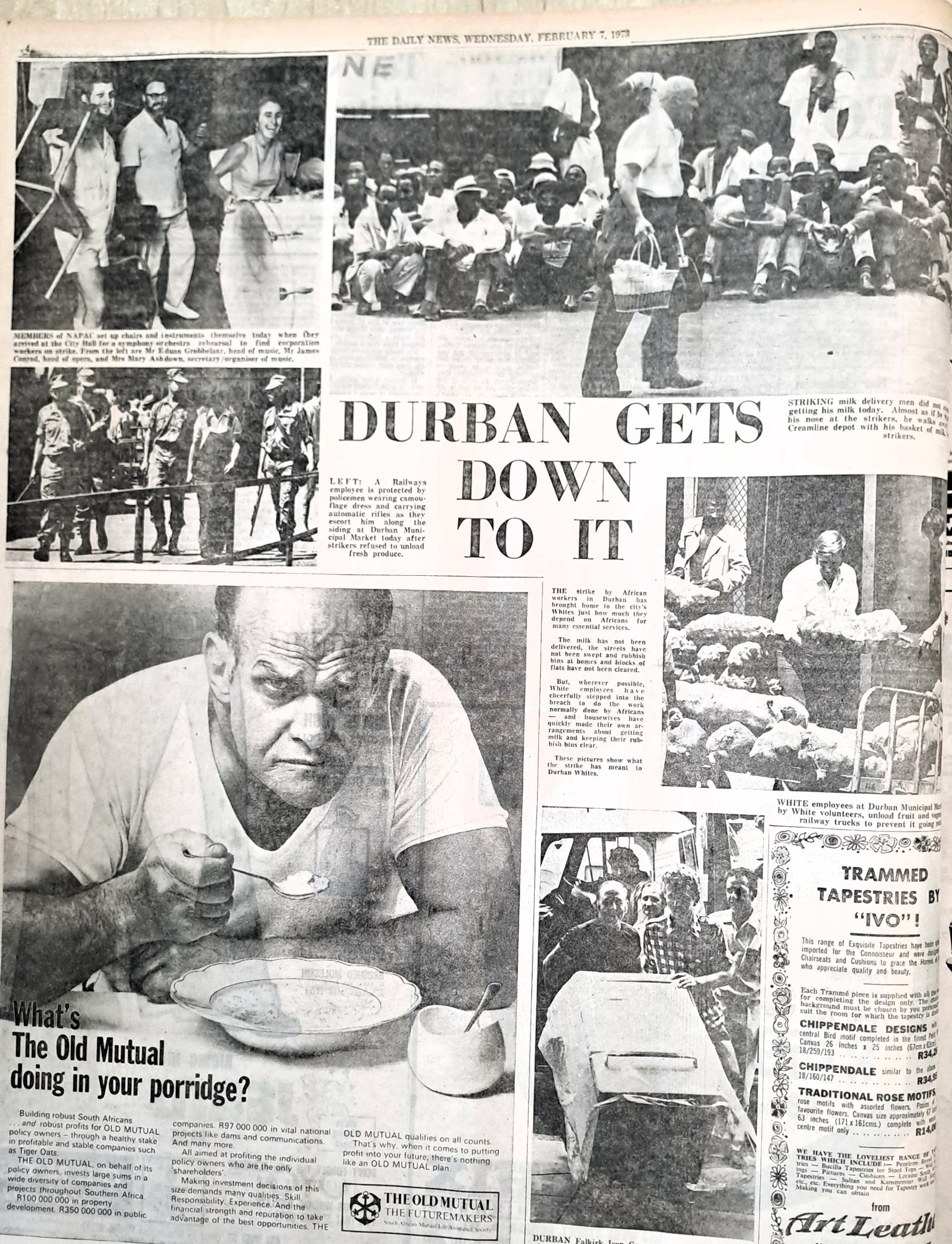

On the 5th of February, 3,000 Zulu municipal workers, including street cleaners and refuse collectors, went on strike, bringing Durban’s essential services to a halt. On the following day, the number of strikers increased to 13,000. Durban’s Municipal Management (then controlled by South Africa’s main opposition party) responded with an offer that was rejected by the strikers.

The strike action in this sector grew as Zulu workers from other factories and areas further afield – such as in the provincial capital, Pietermaritzburg, and in Port Shepstone on the South Coast, joined the Durban municipal workers. Soon some 30,000 workers were involved.

Management-level volunteers stepped in to assure operations at the municipal market