CAPTAIN KEITH COSTER, SAAF:

PRISONER OF WAR: PART II (FINAL)

Gerry van Tonder

(© text)

Continued from Part I, in which Lieutenant General Keith Coster, Commander of the Rhodesian Army, 1968–72, relates his experiences as a World War Two prisoner of war. Serving at the time with the South African Air Force, Coster was shot down in North Africa and incarcerated in Italy until the Fascist regime fell. Together with thousands of other POWs, the Germans transported Coster out of Italy by train.

I think we spent two nights and two days in the gloom of the cattle trucks before the train stopped at Innsbruck in Austria. We were allowed out of the trucks and, being desperately thirsty, made immediately for a small stream that ran alongside the railway line. The water, which came down from the mountains towering above Innsbruck, was crystal clear and icy cold. It was the most refreshing thing I ever remembered. I fell in love with Innsbruck on that day in 1943 but never managed to get back there as a free man until September 1999, fifty-six years later.

We were soon back in the cattle trucks and on our way to Germany once again. Our next stop was at a town called Moosburg, where we detrained and put into a transit POW camp for a few days. The Moosburg camp contained POWs from all the countries fighting Germany, including Russians. One of the bungalows housed only Russians, and on one occasion while we were there, the Germans ordered everyone to parade on the parade ground. The Russians refused to obey the order, so the Germans opened the doors at each end of the bungalow and sent in three or four German Shepherd dogs to force the Russians out. The dogs were never seen again. The Russians killed them and ate them!

German camp guard with his German Shepherd.

I cannot remember when or how long we stayed in Moosburg, but we were soon back in the cattle trucks and on our way to what was meant to be a permanent camp near Stuttgart. I remember virtually nothing of this camp either, or how long we spent there: it could have been weeks or month–probably a month or two.

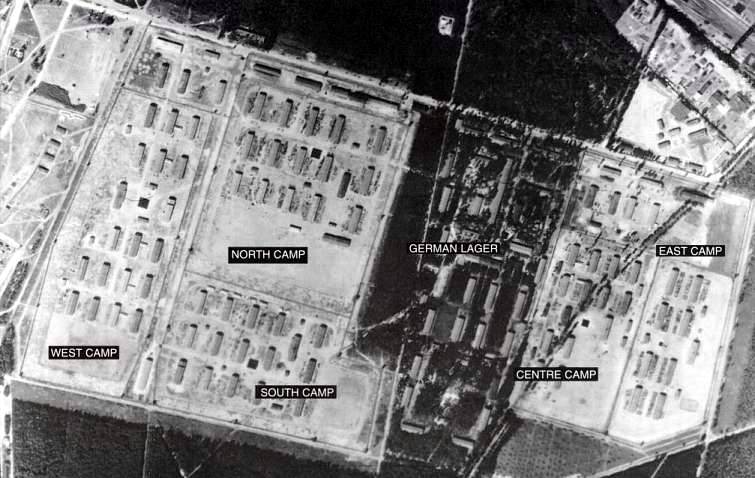

Then the Germans announced that all captured air force officers were to be removed from the Stuttgart camp and transferred to an exclusively air force POW camp known as Stalag Luft III. Some of the South African Air Force officers decided that they would rather stay with their friends in Stuttgart and proceeded to rid themselves of anything–badges, buttons, wings, etc–that might identify them as airmen. My friends and I, however, decided that we had nothing to lose by going to Stalag Luft III. In due course we were marched out of the camp, down to the nearest railway station, and entrained for the longish journey to the east. Stalag Luft III was situated southeast of Berlin, near a village or small town called Sagan. This was probably in November 1943, because all I remember of the journey was that it was snowing heavily, it was bitterly cold, and did not present any opportunity for a possible escape from the train.

Aerial photograph of Stalag Luft III, showing North Camp where Capt Coster was billeted.

We duly arrived at Sagan, noting that the area was very flat and fairly heavily wooded with pine trees. Stalag Luft III was a large POW camp, divided into a number of compounds. We were put into the north compound, which consisted of a number of long, wooden bungalows with a central corridor running from end to end, with rooms on each side. Some rooms held four men, some eight.

Our beds were double-decker wooden bunks with slats across–known as bed board–which supported a thin and uncomfortable coir mattress. All the bungalows were raised off the ground so that the German security guards–known as ‘ferrets’–could check on possible tunnelling activities.

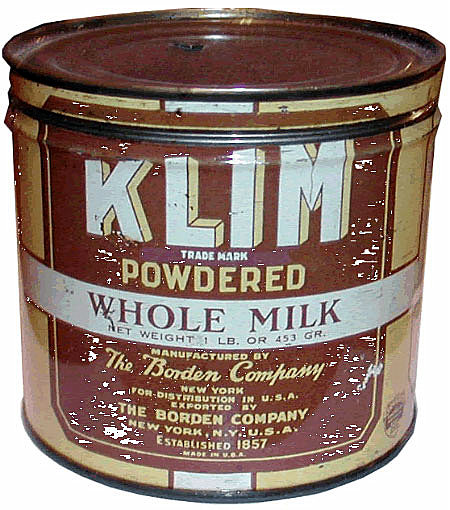

The rooms had an iron pot-bellied stove that kept us warm in winter, and enabled us to brew-up tea which came to us in the Red Cross parcels. When the stoves were not lit, tea water was brewed up in what we called a ‘stufa’, a very skilfully constructed little stove made from empty Klim powdered-milk tins, which heated water very rapidly. Balls of paper were used as fuel. Klim tins, joined together to form a pipe, were also used to convey air to the face of a tunnel for ventilation, while bed boards were used to shore up tunnels and prevent them from collapsing.

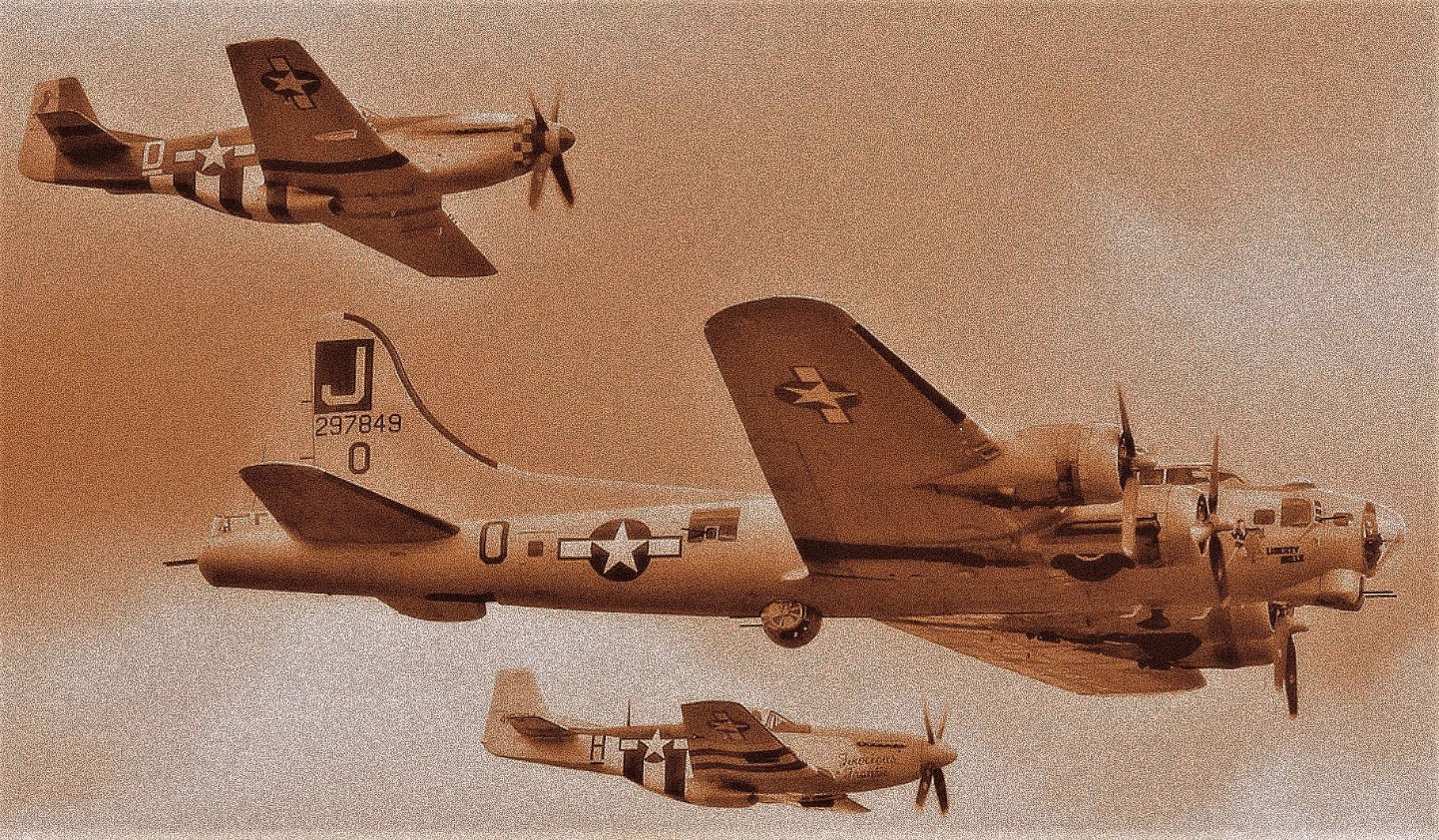

We soon settled into our new environment, making many new friends amongst the hundreds of fellow air force officers there. I suppose the majority were Royal Air Force officers, most of them shot down in night-bombing raids over Germany. Later we had a huge influx of Americans when the US 8th Air Force started daylight raids with [Boeing] B-17 bombers. This was before they had Mustang fighter [North American Aviation P-51] escorts to keep off the German [Messerschmitt Bf] 109s and Focke-Wulf Fw 190s.

American B-17 bomber with P-51 Mustangs escorting.

There were also Australians, Canadians, New Zealanders, Rhodesians, South Africans, Poles, Czechs, Frenchmen, Hollanders, Norwegians, etc. Jack Parkinson, who was there when I arrived, became my best friend, and we remained together until the end of the war. Other good friends I had there were Jack Robbs, who was on my course at the SA Military College, Johnny Eccles, and a senior cadet, Con Norton, a well-known South African war correspondent whose brother was editor of the Cape Times.

There was also Paul Brickhill, an Australian war correspondent, who wrote the story of ‘The Great Escape’ (later made into a film starring Steve Macqueen), Jim Verster who, after the war, became the head of the South African Air Force, Tony Parker, later to be the Secretary for Defence in Rhodesia, and many others.

I had an American chum called Jack Fielding who, in peacetime, had been a Golden Gloves lightweight boxing champion. He taught me a lot about boxing too. At one stage, we had an American lieutenant-colonel in our room called Jamie Murray. He was a delightful chap and very easy to get on with.

He bailed out of his Flying Fortress [B-17] at 30,000 feet, and decided to free-fall most of the way before opening his parachute. He became so intrigued with the free-fall, that he only just got the parachute open in time. Also in the camp was an RAF Sergeant Alkemade*, who was blown out of a Lancaster bomber without a parachute. He fell from about 16,000 feet and landed in a very deep snowdrift. He sprained his ankle and lived to tell the tale!

[*RAF gunner Sergeant Nicholas Alkemade (21) was sitting in the tail end of a Lancaster bomber when a German fighter plane opened fire. His plane, Werewolf, began to go down in flames and the pilot addressed the crew over the crackly intercom, telling them to jump. Alkemade stood in the plane, flames licking his flight suit, and in the chaos was forced to make an unenviable decision. The question was whether to stay in the plane and fry or jump to his death. He decided to jump and make a quick, clean end of things, so he backed out of his turret and dropped away.]

When our intake moved into Stalag Luft III, there were three tunnels under construction. One was discovered, but the Germans knew nothing of the other two, so their construction continued throughout the winter. Some of us volunteered to join the tunnel crews and were assigned as ‘duty pilots’.

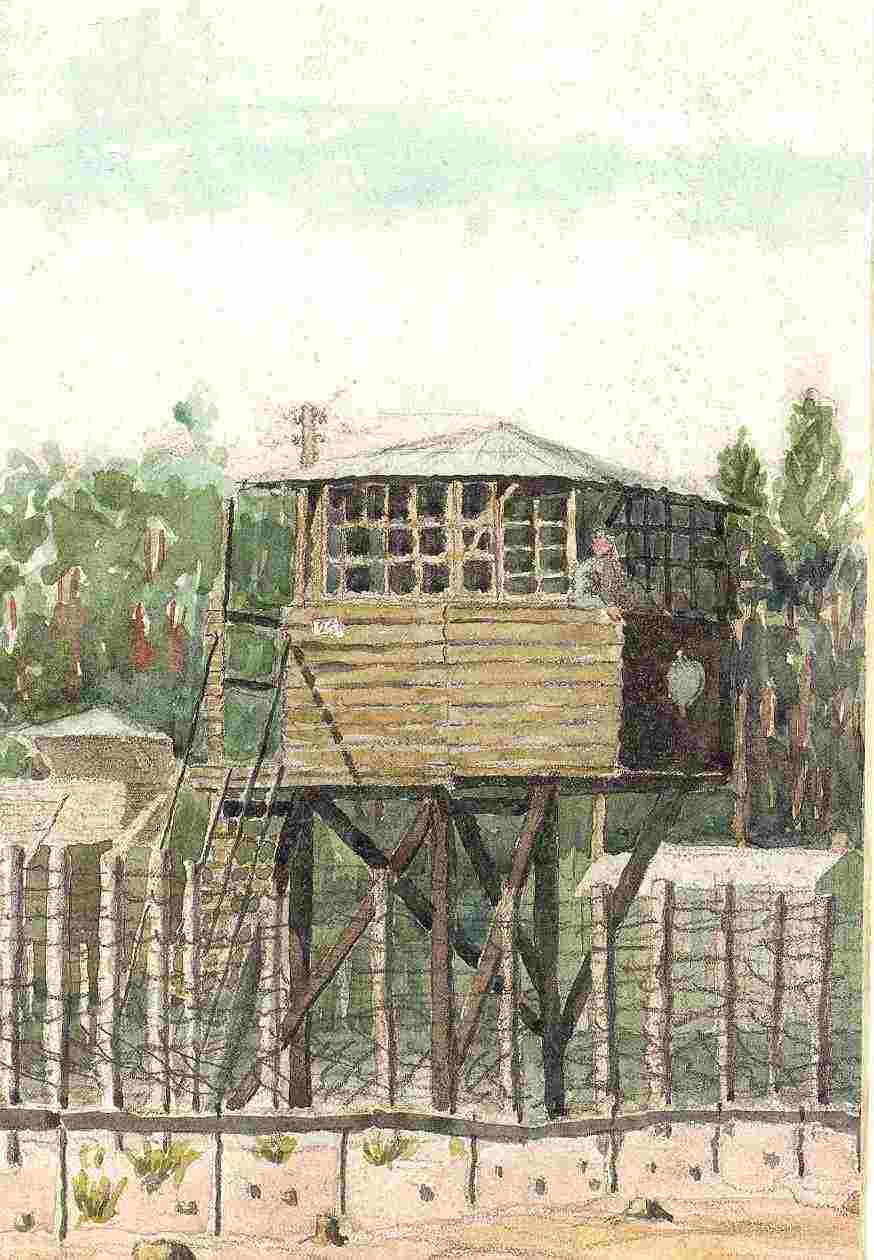

German ‘ferrets’ whose sole duty was to search for POW tunnels.

Our function was to watch for, and report on, the movement of ferrets. Our organisation was such that the position of every ferret was known at every minute of the day or night. If a ferret was known to be moving towards a bungalow from which a tunnel was being dug, the word flashed from one duty pilot to another, causing work to cease at the tunnel mouth, until the danger had passed. The same organisation worked to make it safe for the BBC news to be read out to all the occupants of a bungalow each day. A clandestine radio receiver, hidden well below ground, received the news.

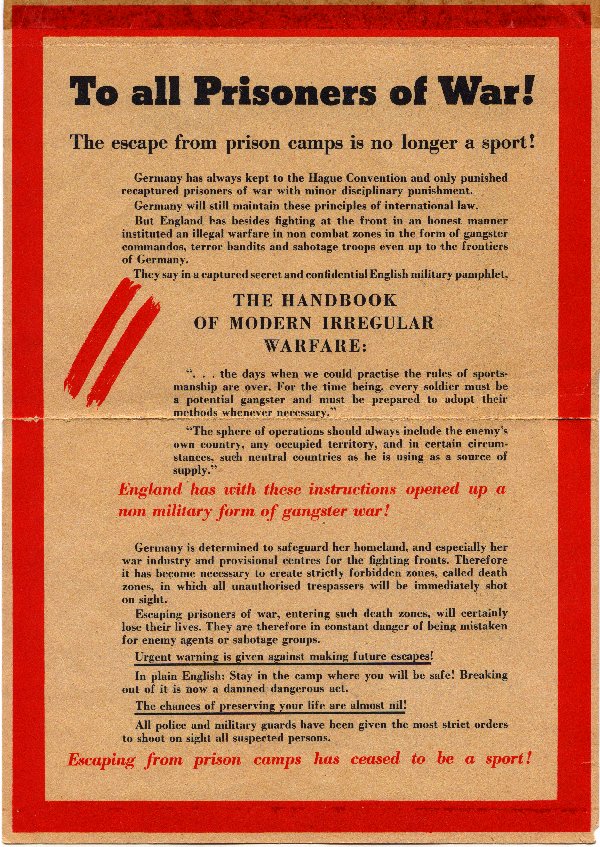

Chilling message from their German captors: Allied POWs are warned that they will be shot dead if they are caught after having escaped.

Every morning all the POWs who were not in the camp hospital had to attend ‘apell’: a parade of every able-bodied prisoner, where we were counted and also addressed on any subject which the Germans wanted to convey to us. In the summer, this was no real hardship, but in the East German winters (we were not far from the Polish border), it was just plain hell. Sometimes, to punish us for perceived misdemeanours, we would be kept on apell for hours on end in the snow and the freezing wind.

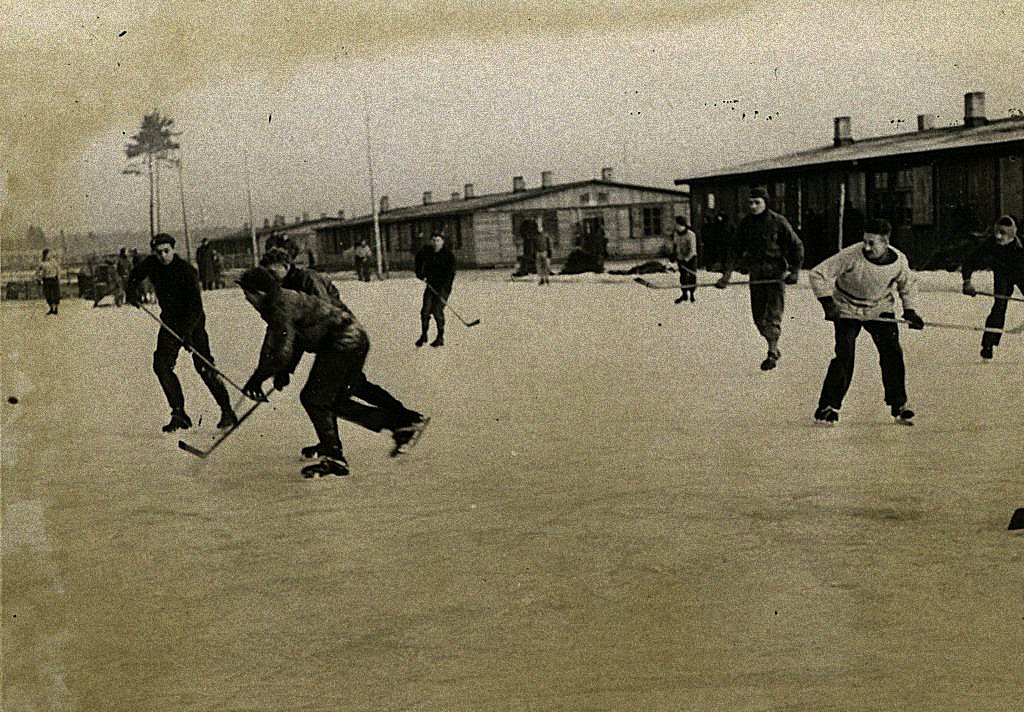

Every day started with apell, and when it was over, we more or less had the day to ourselves. Some would talk, some would read, some would attend classes to learn German or French or any other language that was being offered. Some would be rehearsing for a camp play, others like Paul Brickhill and Con Norton, would be busy with the manuscript of a book. When the weather was good, many would indulge in physical exercise ranging from gymnastics to weightlifting. In the winter, it was so cold that we would make an ice-skating rink in no time at all. The fire buckets in each bungalow would be filled with water, and one would race out to the site at the skating rink and pour the water onto the ground where it froze instantaneously, before rushing back for another one. In thirty minutes, one would have a skating rink large enough to play ice hockey on. Skates were provided by the International Red Cross.

Ice hockey at Stalag Luft III.

Probably the most popular pastime with the majority of POWs, was ‘pounding the beat’, which meant walking round and round the perimeter track that was overlooked at every point by the German sentries in the ‘goon boxes’ or ‘goon towers’, which were erected all around the compounds. One met airmen from every part of the Commonwealth, as well as from America, and those countries of Europe at war with the Germans. One of the friends I made at that time was a squadron leader from New Zealand called Len Trent. He told me, as we pounded the beat together, about how he came to be shot down. It was an incredible story, and when he had finished I said to him, “Len, what you have just told me sounds like a citation for a VC.” Much to my delight, when the war was over, I read in an English newspaper that Squadron Leader Len Trent of New Zealand had been awarded the Victoria Cross.

The large open space between the bungalows and the perimeter wire was used for sporting activities of all kinds, from rugby and soccer to gymnastics. On one occasion, we organised a huge athletics meeting between North America (the United States and Canada), the British Isles, Europe, Africa and the Antipodes (Australia and New Zealand). The climax of the meeting was a medley relay race in which I ran the 440 yards (now 400 metres) for Africa. Despite being perpetually hungry, I was very fit. When I took over the baton, I was stone last, but I went off at a great pace and to my surprise eventually passed all the other runners on the track. I handed over to a chap from Kenya who had to finish by running the 880 yards. He was a superb athlete who had no difficulty in maintaining the lead that I had given him, and so Africa won the premier event of the day. Not a big deal as they say today, but very satisfying in those circumstances.

POW stage productions such as the one above were very popular, with some of the men looking very convincing in female attire.

Another very popular activity amongst the ‘Kriegies’ (short for kriegsgefangene, German for POWs) was that produced by the Dramatic Society who put on all the plays that were then on in the West End of London. There was some extraordinarily good talent to be found in the POW camps. A number of RAF officers who acted in the camps during the war became very well known on the London stage after the war. The big problem was that there were no women in POW camps, so all female parts had to be taken by men. In Stalag Luft III we had an RAF officer called ‘Junior’ Dowler who, when made up as the female lead for a play, was nothing short of incredibly beautiful, and many a POW found himself ‘in love’ with that gorgeous girl! On one occasion, the play being enacted by the Dramatic Society was ‘Arsenic and Old Lace’. We were all very amused to hear that an American air force officer had arrived in the camp, having been shot down in a B-17, with tickets in his pocket for the London show of ‘Arsenic and Old Lace’. So’ in the end, he saw it in Germany.

There seemed to be no possibility of escape from Stalag Luft III, except by tunnels from inside the compound, under the wire, and eventually coming up some distance outside. As I have already mentioned, when I moved into Stalag Luft III in November 1943, or thereabouts, there were three tunnels under construction. One was discovered and closed down by the Germans, while work on the other two continued. The tunnels were code-named Tom, Dick and Harry. Harry was the tunnel chosen for the ‘Great Escape’, which took place on the night of 24th March 1944.

Diagram of the north compound in Stalag Luft III, showing the positions of the ‘Tom’, ‘Dick’, ‘Harry’ and ‘George’ tunnels dug by Allied POWS as escape routes. ‘Harry’ , immortalised in the movie The Great Escape, proved to be the most successful escape in terms of numbers, but also the most disastrous, with fifty recaptured POWs summarily shot by the Germans.

The plan was to get 250 POWs out through the tunnel before first light the next morning. Only a limited number of would-be escapers could be provided with suitable civilian clothing, money, maps and rations, so the selection was based on those officers who had been intimately connected with tunnel construction from its inception. The balance, if they managed to get out, would do the best they could in their air force uniforms and what rations they had saved up.

No one expected them to get very far, but at least they would keep the follow-up forces busy looking for them, and perhaps help to take the heat off those who were better equipped for escaping. All of us who had had any hand in the escape organisation drew cards to establish the order of going through the tunnel. My number was such as to make it unlikely that I would get out that night. I was bitterly disappointed at the time, but said a silent prayer of thanks when the events of that fateful night unfolded.

Everything that could go wrong with the tunnel went wrong. It was late in ‘breaking’, coming up sixty feet short of where it should have come up. Some escapees were stuck fast in the tunnel when all the lighting went out in the tunnel because the RAF were raiding Berlin ninety miles away, so the Germans turned off all the electricity at Stalag Luft III. Instead of getting 250 men through the tunnel, about 80 got through.

A couple of days later, we were informed that on the orders of Adolf Hitler himself, fifty of these were executed by shooting. Their ashes, in fifty small urns, were sent back into the compound for all the rest of us to see. The impact of such an outrageous action can well be imagined. Fifty hale, living men – our friends – two days ago, and now fifty small urns containing their ashes. Our hatred and detestation of the Germans knew no bounds.

The memorial to the 50 executed Allied escapees from Stalag Luft III at Żagań, Poland.

Eventually life, such as it was in a POW camp, returned to normal. By listening to the BBC news every day, clandestinely of course, we were aware that the tide of war was turning against the Germans. Hitler’s invasion of Russia–exactly as in the case of Napoleon’s invasion of 1812–turned sour, forcing the Germans to start the long and terrible retreat from Russia back to their homeland. German losses in the battle for Stalingrad were enormous. At last the writing was on the wall.

RAF Bomber Command carried the air war to Germany, sending as many as 1,000 bombers a night to Berlin and many other major German cities. The US Air Force too, stepped up its daylight raids on the Reich. We often witnessed 1,000 or more B-17s spread across the sky from horizon to horizon, while air battles between the escorting Mustang fighters and the German 109s and 190s raged around the line of bombers. Then on 6th June 1944 came the invasion of the continent from Great Britain: Operation Overlord, the greatest seaborne invasion that the world has ever seen. The Allied forces, with Americans and British in the majority, landed in France. As they built up their forces in the bridgehead area, they turned east and swept towards Germany.

We all thought that the war would be over before Christmas 1944, and that we would be back home for Christmas. But it wasn’t to be. The war dragged on with the German forces being squeezed more and more between the Russians from the east and the Allied forces from the west. In the south also, the Allies, driving up through Italy, helped to squeeze the German forces back into the heart of Europe.

A column of Allied POWs on the march in Germany.

In the first months of 1945, Germany was in the grip of a harsh, bitterly cold winter, as well as being rolled up from both east and west as the Russians and the Allies closed in on the country.

On the night of 16 February 1945, it was snowing heavily over Stalag Luft III when, without any warning, we were told to pack our few belongings and be prepared to move out of the camp within an hour. We could at this stage hear the Russian and German guns as they engaged in an artillery battle on the River Oder, which was the border between Poland and Germany, about fifty kilometres to the east. It never occurred to us, though, that we would actually be moved from Stalag Luft III. However, every POW had some rations saved from Red Cross parcels for use in an emergency, so we packed these, together with any spare clothes we had, and a blanket each.

The Canadians, who were used to snow, suggested that we should try to provide ourselves with little sledges for carrying our belongings. Jack Parkinson, Jim Verster and I hastily knocked up a sledge using bed boards. We had the brilliant idea of cutting strips of metal from Klim tins, which we nailed to the sledge’s runners to obviate too much wear. We dressed in everything we had, packed the rest on the sledge. We were ready.

I think it was about midnight when the guards chased us out of our barracks and got us formed up in columns of three facing towards the exit from the camp. It was freezing. Not only was it snowing hard, but there was an icy wind blowing off the Silesian plains which introduced a wind-chill factor that dropped the temperature alarmingly. Then off we set, out of the camp we had been in since November 1943, before turning towards the west, away from the advancing Russian forces. We plodded on through the snow, with heads down to avoid the icy wind but beards and moustaches froze into solid ice and morale dropped to rock bottom.

When the first grey streaks of dawn lit the wintry sky, one could imagine that this was like Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow in 1812. Two of us pulled the sledge with all our worldly belongings packed on it, while the third just plodded until his turn came round. Our sledge became more and more difficult to pull. We presumed that we were tiring, but we had to keep going. The awful weight of the sledge not only broke our backs, but nearly our spirits as well.

Eventually after some hours, we decided to do without the sledge and backpack instead. It was when we offloaded the sledge that we discovered what the problem was. The Klim tin ‘runners’ on the underside had lost the nails that held them fastened to the wood. They had turned downwards into the snow, so that instead of helping the sledge to slide over the snow, they had become brakes, which made pulling virtually impossible. Once we had ripped the tin runners off, the sledge once more pulled normally, and off we went again.

The blizzard lasted all day and conditions worsened considerably. That night, nearly dead with fatigue, we slept beside the road in total blackness and on the snow. Jack Parkinson and I each had a blanket, so we put one down on the snow, then lay huddled together for what little warmth we could get from each other’s bodies and put the other blanket on top. It was a night neither of us would ever forget. Years later Jack would delight in shocking people by telling them that Keith Coster was the only man he had ever slept with!

By the following night, we had reached a small German village, or town, called Muskau. To our extreme relief, billets were found for all the POWs on the march. Jack, Jim and I found ourselves billeted in a disused cinema, from which all the seats had been removed, so although we had to sleep on the floor, we at least had a roof over our heads, which held off the snow and the howling, icy wind. There were so many of us packed into the cinema, however, that we lay like sardines in a tin. If one had to get up in the night to go outside to spend a penny, one inevitably trod on some recumbent form in the total darkness, rewarded with a flow of invective the like of which one had never heard before.

We spent a few days at Muskau until the blizzard stopped and the weather began to clear a little. Then we were on the march again to a town called Spremberg, which was on the railway line.

Cattle trucks were a common means of transporting Allied POWs around Germany.

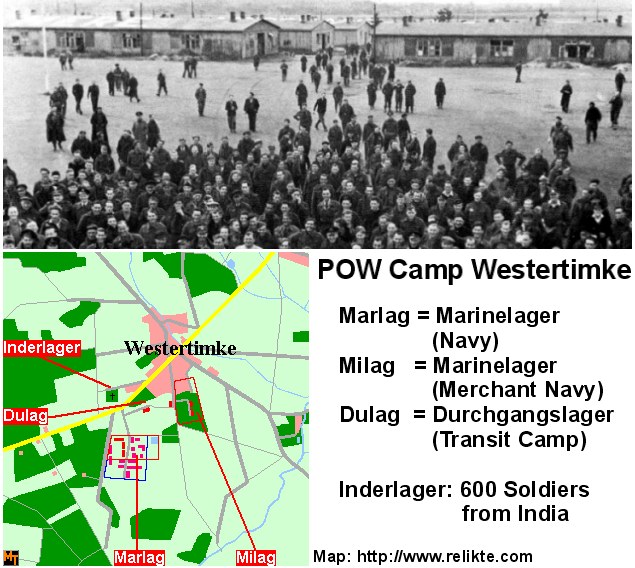

Here we would be crammed into cattle trucks for a long and desperately uncomfortable journey across Germany from east to west. One of our concerns was the possibility that Allied fighter aircraft would strafe our train, or that the British or Americans would bomb us when we were being shunted about in railway marshalling yards. However, this never materialised, and eventually we reached the destination that the Germans had set for us. It was a place called Westertimke on the outskirts of Bremen. We arrived there at night and in pouring rain. All we wanted was to get inside, even though it was another POW camp.

Strangely enough, the Germans were very tardy about letting us in, until Jim Verster went up to the gate and shouted for the commandant. When he appeared, Jim threatened him with harsh action after the war if he did not immediately open the gates and let us all in. This worked. Hundreds and hundreds of sick, cold, wet, hungry and weary POWs were permitted to get out of the rain and find a place to doss down for the night.

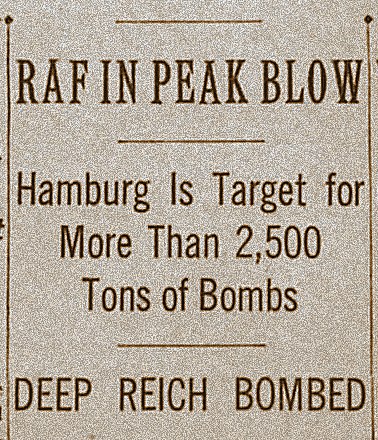

Our first journey was over. It commenced on 17th February 1945 and ended at Westertimke on the last day of February–a total of eleven days. The camp we were now in had a majority of naval and merchant navy officers, but we hardly had time to make friends there because the war was rapidly drawing to a close. Germany was shrinking in size, as the Russian forces closed in on Berlin from the east and the allied forces from the west. Our camp was close enough to Hamburg for us to be able to witness the night bombing of that city. It was a fearful sight to behold. The night was lit up almost like day from the fires caused by the bombing, and the casualties caused to the German people were terrible.

Operation Gomorrah firebombing of Hamburg.

On April 15th, four days before my 25th birthday, the Germans decided to move us once more. This time we were to move eastward, away from the advancing Allied forces. We set off along country roads heading towards Hamburg, where we would cross the River Elbe into Schleswig-Holstein. By now it was early spring in Europe and there was plenty of blue sky and sunshine, added to which was the certainty that the war, which had been going for five-and-a-half years, would very soon be over.

Our second march, by comparison with the evacuation from Stalag Luft III, was a pleasure. As we passed through villages and farms, we were able to do a little trading with the locals, exchanging chocolate and cigarettes from the Red Cross parcels for eggs and fresh vegetables. When you haven’t eaten an egg for three years, it becomes a very desirable and prized item. We slept in fields beside the road, where we were invariably kept awake by low-flying Allied aircraft which, even at night, kept up the air offensive against German targets. They would drop parachute flares that turned night into day, then strafed or bombed anything that moved. During the day too, we were constantly on the lookout for British or American aircraft that were very active over the sector in which we were moving, ahead of the advancing Allied forces.

There was at least one awful tragedy. A column of naval POWs just in front of us was strafed and sixty killed before the column could scatter. The senior British naval officer, very bravely, donned his naval jacket and cap and ran to the crown of the road, raising his arms into the air to display his British uniform, but he too was gunned down by one of the fighter aircraft and killed.

Now close to freedom, Capt Coster and his fellow POWs moved through the camps in the German town of Westertimke.

It took four days to move from Westertimke to Hamburg. We crossed the Elbe–I don’t remember whether by bridge or by ferry–coming out into beautiful farming country on the other side. The crossing of the Elbe was on my birthday. We continued to move slowly into the countryside of Schleswig-Holstein towards Lübeck. The German guards, who were looking after us, knew it was only a matter of days before we would be freed and they would become prisoners of war themselves. All their arrogance disappeared like mist in the morning, as they began to behave like friendly, fellow human beings.

About the end of April, we came to a really beautiful German farm, where our captors arranged with the farmer that we should be billeted at the farm for a couple of days. Accordingly, we moved in and found ourselves a place to sleep. Jim, Jack and I found a loft over a barn filled with straw. It was warm, dry, and very comfortable. I think it was 3 May 1945 when we snuggled into the straw to sleep.

We woke early in the morning to the sound of machine-gun fire, which meant that the Allied forces were no more than a few kilometres away. The German guards had melted away during the night. I was free after two years and eight months of captivity.

Some enterprising POW had erected a sign near the farm’s gate on the road, which read, “Good pull in for tanks”, based on the British sign “good pull in for lorries” to indicate a stopover for lorry drivers. Well, no tanks pulled in to our farm, but a British army scout car, containing a private soldier and a corporal, saw the sign and drove up the access road to the farm buildings where we were billeted. The corporal gave us the news officially that we already knew: the German armed forces were in full retreat and that the war would be over in a couple of days. This was 4 May 1945, Mum’s 26th birthday!

British army Humber scout car, with mounted Bren Gun.

We were all really too stunned to be wildly excited, so we just waited patiently for whatever would happen next. My memory of what did happen next is very vague. I think a POW liaison officer contacted us, and that he arranged transport to take us to an assembly area from which we would be flown to England. If my memory serves me correctly, we were taken in three-ton lorries from the farm in Schleswig-Holstein to Lüneburg where, in fact, the armistice was signed between the Allied and German forces, officially ending the war that had started on 3 September 1939, five years and eight months before.

What I do remember is that in the afternoon of 7th May, while we were waiting in Lüneburg to be flown back to Britain, three of us, myself, Johnny Eccles and Con Norton, decided to go for a walk. Don’t ask me what had happened to Jack Parkinson and Jim Verster at that stage. We walked out into the countryside, and were quite close to an aerodrome that had obviously been hurriedly vacated by the Germans, as it was quite deserted. We then saw a Dakota coming in to land on the runway. When the Dakota stopped, we climbed through the aerodrome fence and ran up to talk to the Dakota’s pilot. He was a Canadian flying officer who asked us where the hell he was! We told him and then got chatting to him. He told us that he had to go first to Brussels and then back to England that afternoon. We told him we were ex-POWs and asked whether we could hitch a ride back to the UK with him. He said, “Sure, hop aboard.” So we did just that.

THE END

Comment by Brig HB Heymans (SA Police – Ret)

I had the privilege to work with Gen Keith Coster – he was later employed by the Secretariat of the State Security Council in Pretoria. He was a fantastic officer, very knowledgeable and kind – a true Officer & Gentleman! Salute!