CAPTAIN KEITH COSTER, SAAF: PRISONER OF WAR: PART I

Gerry van Tond

(© text)

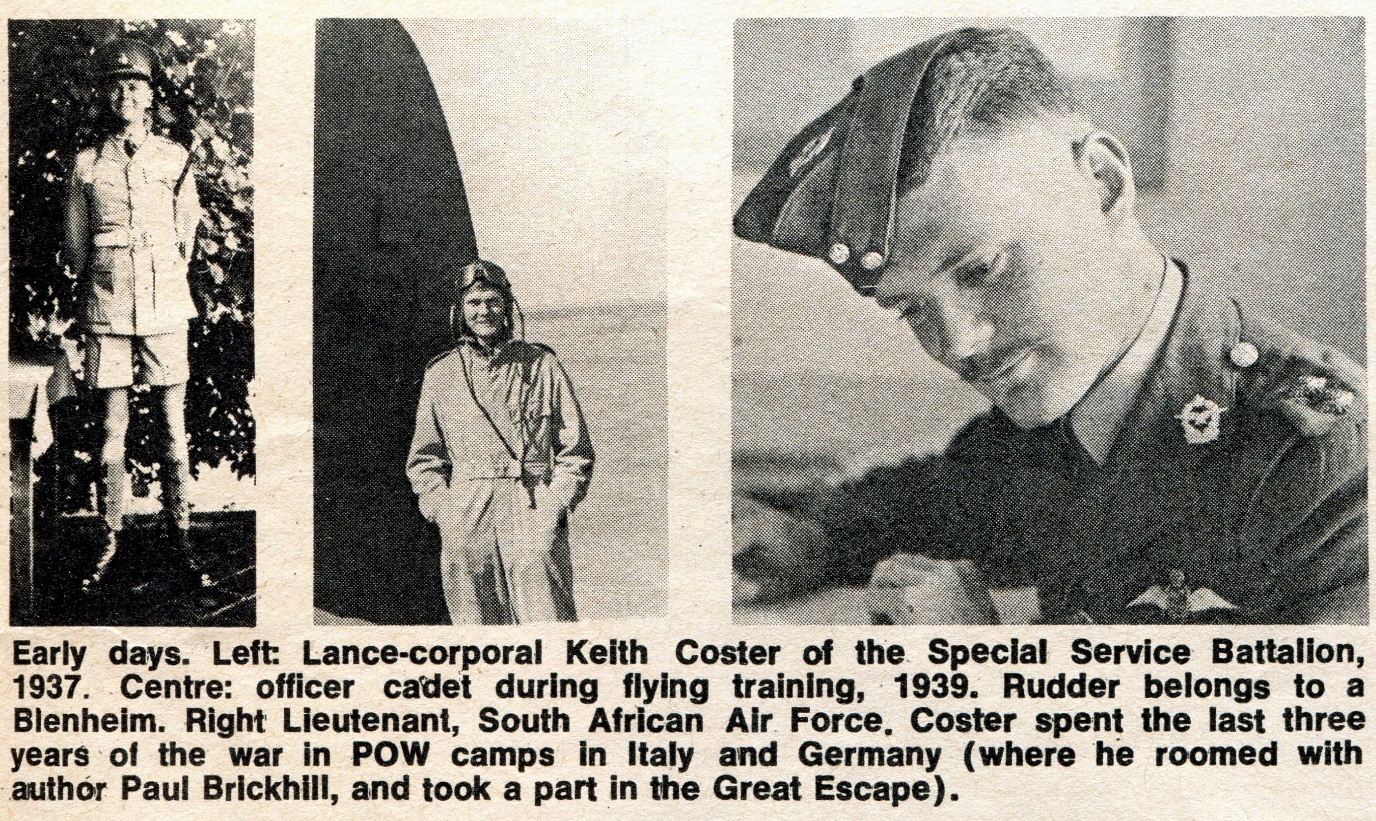

Lieutenant-General Keith Coster ICD, OBE, SSAS, was a South African Air Force and army officer who rose to command the Rhodesian Army from 1968 to 1972.

In May 1937, Coster enlisted in the Special Service Company, Royal Durban Light Infantry, South African Permanent Force. A year later, he commenced officer training at S.A. Military College, Voortrekkerhoogte, as a cadet pilot.

On 4 September 1939, Coster completed the pilot’s course, and transferred to Zwartkop Air Station, Pretoria. From his personal papers, the following is a verbatim account of this part of his military career.

One minute we were officer cadets earning five shillings (50 cents) a day, and the next minute we were 2nd lieutenants and our pay would go up to fifteen shillings (R1.50) per day! We all had a couple of beers to celebrate this fantastic stroke of luck, and no more work was done on that Wednesday, 6 September 1939. At that stage we were all very close to getting our ‘wings’ for flying, and for the next ten days we put in quite a lot of flying time. On 16 September, I did my flying test with Major S.A. Melville and qualified for my ‘wings’, which meant that I was considered capable of carrying passengers in the air.

I resumed my duties as a specialist air armament instructor at No. 65 Air School on 18 September 1941, but by now my sights were set on getting back to general flying duties and getting into an operational squadron in North Africa where the Allied Forces (British, South African, Australian and New Zealand) were confronting the German Afrika Korps.

We completed the journey from Pretoria to Cairo on 17th April 1942, two days before my 22nd birthday. It was brought about by a chance meeting with a fellow called Eric Baker who had been at Young’s Field with me earlier on during the war. Eric was by now a lieutenant colonel in the South African Air Force (SAAF) and had a Distinguished Service Order (DSO) and a Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC). He asked me where I was headed and I said that I was in Egypt to fly bombers. Eric, being a fighter pilot set about convincing me that it was far better and more exciting to be a fighter pilot than a bomber pilot.

So the following day I asked for an interview with Brigadier Peter Hingeston, the senior SAAF officer in Cairo, to whom I put my case for a change in my posting to fighters. He was agreeable and made immediate arrangements for me to attend a fighter OTU (Operational Training Unit). Until the next course started I would be posted to the SAAF base at Amyria from 20th to 28th April. In the event, I did not stay in the SAAF base until the 28th.

On 2nd July we were ferried out to LG (Landing Ground) 85 in the desert, to join what was known as 233 Wing, which consisted of No’s 2, 4 and 5 Squadrons of the South African Air Force, but which was commanded by a Group Captain Beresford of the Royal Air Force. In an introductory speech, he told us that things were pretty rough in the desert at that time, with a great many casualties to air personnel and aircraft. I remember his closing words, “And if you break any of my bloody aircraft I’ll have your guts for garters.” We all dutifully laughed.

Curtiss Tomahawk, No. 5 Squadron, SAAF.

I was assigned to No. 5 Squadron, which was equipped with Tomahawks. Dick Clifton, much to my envy, went to No. 4 Squadron, which had Kittyhawks, which were much superior to the ‘Tommies’. Fighter squadrons usually had twelve operational aircraft, seldom more, and often less if there had been casualties. The CO (Commanding Officer) of No. 5 Squadron up to a few days before had been Dennis Lacey. He had been shot down and killed, as had ‘Cookie’ Botha, one of my fellow cadets who, in the time that we had been at OTU, had shot down five enemy aircraft, been awarded a DFC (Distinguished Flying Cross), and then had been shot down himself. Our Acting CO at that stage was a Captain van der Spuy.

On 11 July 1942 a medium cover operation to 18 Bostons was scheduled, and we took off in the early afternoon. Flying as my ‘number two’ was a young 2nd Lieutenant called Lionel Rapp. His function was to keep an eye open for any attacks from enemy fighters and thus to protect my rear. We were flying at about 8,000 feet when, all of a sudden, we were ordered over the radio to attack a formation of German Stukas that were dive-bombing Allied forces in the same general area as our Bostons were going to bomb in.

Almost immediately, I spotted them—and they obviously had seen us—because they stopped their dive-bombing and headed downwards with their throttles wide open. My No. 5 Squadron formation broke away from the Bostons and dived in pursuit of the Stukas. As we hurtled towards the ground, the first thing of which I became aware was out of the corner of my left eye: a burning Tomahawk completely enveloped in flames. I presumed it was Lionel Rapp, which was later confirmed. It could mean only one thing: our formation had been ‘jumped’ by ME 109s, just as we had jumped the Stukas.

At this point I had my sights on a Stuka and I fired my four .50 Browning guns at him. I know I damaged the Stuka, but whether he went down or not I don’t know, because I became pre-occupied with a sudden loss of my ring-sight that normally imaged on the windscreen in front of my face. We all pulled out of our dive as we were getting dangerously close to the ground, and, as I levelled out, there was an almighty bang. I realised that I had been hit!

Luftwaffe Me-109s over the Libyan desert.

While I was absorbing this development, a 109 (German fighter Messerschmitt Bf 109) passed in front of me and I gave him a burst from my Brownings—but it was not an aimed burst as my ring sight had gone. In trying to follow the 109, it became immediately obvious that my rudder had been shot away because there was no response when I kicked my rudder bar. An aircraft without a rudder becomes a sitting duck, as the basic manoeuvre in aerial combat is to turn into any aircraft that fires at you.

It was obvious that without rudder control I couldn’t make any further contribution to the dogfight, so by the use of ailerons alone, I managed to start a long, flat turn towards the sea when I was hit again. Not being able to turn into my attacker, I had but two alternatives: to climb or to dive. I decided on the latter and dived down to a few hundred feet above the ground.

In the dive I was hit a third time from directly behind—a long burst which started my Tomahawk burning and caused shrapnel wounds in my left arm and in my neck. I could see the long trail of smoke tailing out behind my aircraft and I knew that I had to make a very quick decision. To climb to a height where I could bail out would be inviting further—and probably fatal—attacks, or a complete burnout of the aircraft.

As I was very close to the ground, I decided to put it down on the desert and get out before it went up in flames. I loosened my straps and jumped clear before the aircraft had come to a halt. When I stopped rolling, I jumped to my feet and ran to put as much distance as I could between me and the aeroplane. Seconds later, it burst into flames and very rapidly burnt out completely.

I continued running, but could see the 109 turning and diving down towards me. Then he opened up, and a couple of cannon shells exploded close enough to me to cause rock fragments to penetrate the skin under my jaw. I fell forward as though I had been fatally wounded, and lay spreadeagled on the desert sand. The 109 pilot did another circuit to see whether I would get up again, but as I didn’t, he presumably considered me dead and flew home to his forward landing ground.

When I was satisfied that there was no more aerial activity, I stood up and started running again, to get as far away from the burnt-out aircraft as possible.

Members of the Afrika Korps.

Suddenly I heard something behind me and looked around to see a small reconnaissance vehicle with three Afrika Korps soldiers closing rapidly on me, so I stopped running and turned to face them. One of them could speak some English and said, “For you the war is over. Every day is now Sunday.”

I suppose this was funny, but I wasn’t in the mood for laughing. Just before I left Cape Town in January, I had bought a beautiful Tissot wristwatch, which caught the eye of my captors. The English speaker made it clear that he wanted it. When I protested, a machine pistol was pushed into my ribs, and my Tissot acquired a new owner. They loaded me into their vehicle and went off in search of a casualty clearing station to treat my wounds, which were not in fact very serious, although I was covered in blood.

Having delivered me to the CCS (Casualty Clearing Station), they pushed off back to the war and I saw them no more. After I had been cleaned up and bandaged, I was given something to eat and drink and then put in an ambulance for the night.

I went to sleep almost immediately, only to be rudely awakened by a German doctor who said he was going to sleep in the ambulance, and that I should sleep on the ground outside, which of course I did—and very cold and uncomfortable it was.

The next day I was delivered to a prisoner-of-war interrogation centre, which consisted of some tents and a couple of barbed-wire compounds for the holding of POWs, erected in the desert. Here, for a couple of days, the German interrogator endeavoured to get me to disclose the number of my squadron and other relevant information that would be of value to the Luftwaffe. However, all pilots had been briefed that if ever they became POWs, all that they were permitted to disclose was their number, rank and name. And so for two or three days we verbally sparred. No force or torture was used. Eventually I was discarded and handed over to the Italians.

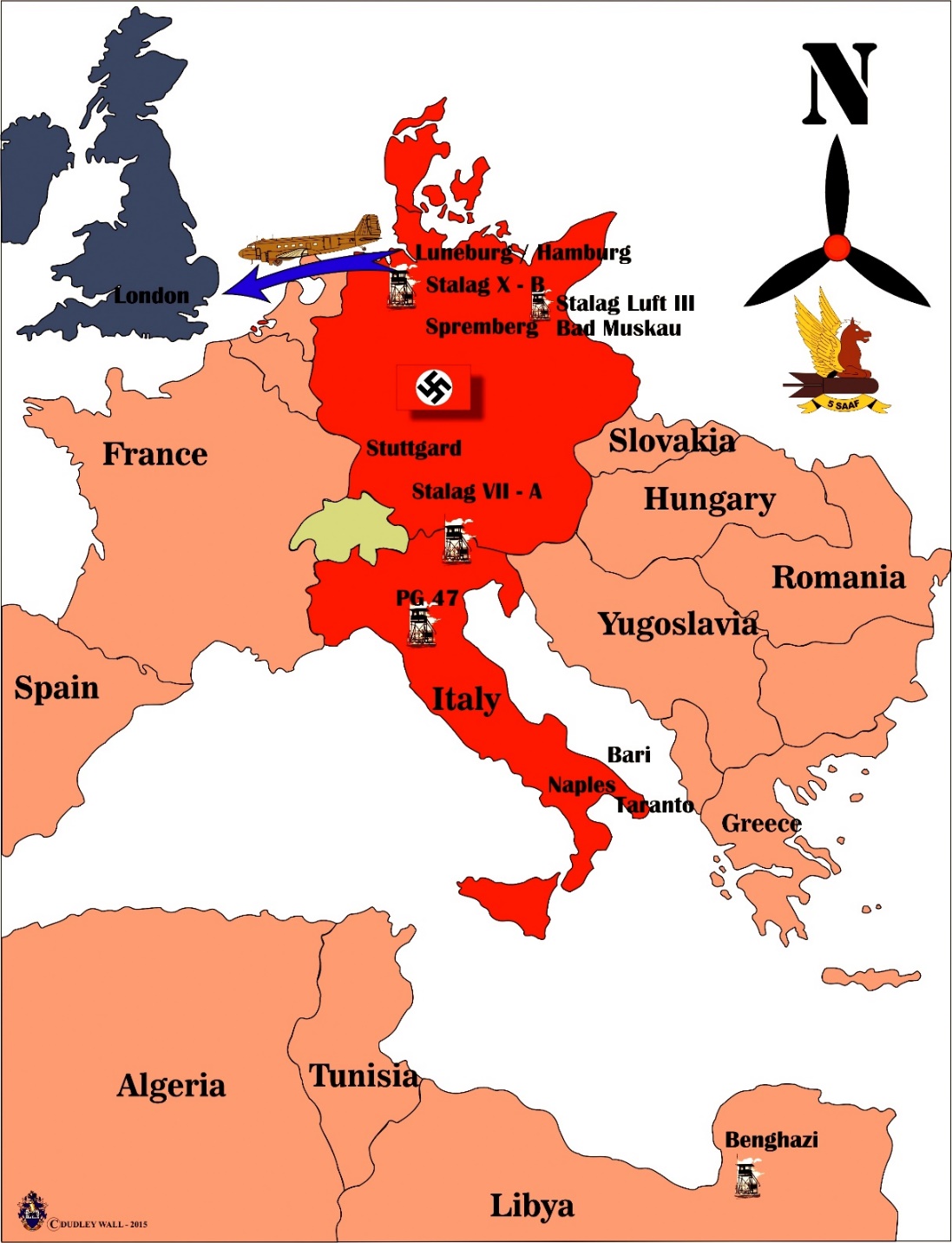

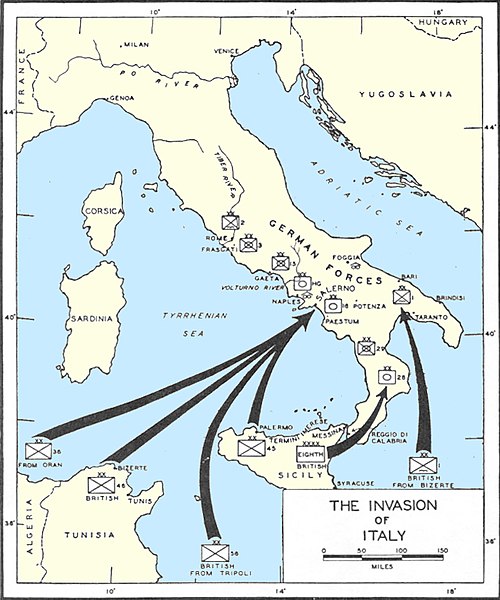

(Map Dudley Wall)

Two weeks before I was shot down, the desert fortress of Tobruk had surrendered to the Afrika Korps, and thousands of South African, Australian and British soldiers had become prisoners of war. They too had been handed over to the Italians for safekeeping, who began moving all POWs into the coastal town of Benghazi, from where they would be shipped across the Mediterranean to the Italian port and naval base at Taranto. I was also moved into Benghazi to join the vast number of South African officers who had arrived there from Tobruk.

Italians watch Allied POWs, Libya, North Africa.

I cannot remember when we left Benghazi, nor the name of the Italian ship that took us across the Mediterranean. The voyage lasted a couple of days, until our ship docked at Taranto from where we were taken by train to Bari and chucked into a POW camp.

I can’t remember how long we were in Bari; not very long I think, as Bari was merely a transit camp. From there a train moved us across Italy from east to west. It was on this journey that I contemplated escaping by jumping from the train. The thought was that one would then wait in the dark beside the railway truck for a goods train to come by, and at the same place where the passenger train had slowed down, jump up onto the goods train and get as far north as possible. I had discussed this with a friend called ‘Bones’ Hobson, who had been my company commander when I joined the Special Service Company of the Royal Durban Light Infantry in Durban in 1937. By this time, I had caught him up and we were both captains.

We got ready for the train to slow down and opened the compartment windows to jump out, but as we were about to go, some chap from the compartment ahead of us beat us to the jump. We expected the Italian guards to open up with their rifles on the man we could see crouched beside the track, his spectacles glinting in the moonlight, and hesitated. Then the train started to pick up speed again and the moment was lost.

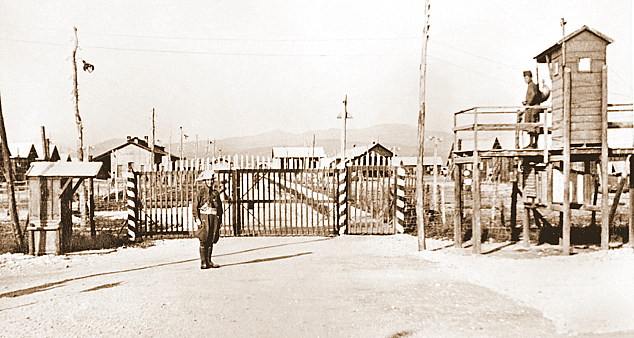

Italian campo perimeter fence.

We went on westwards across southern Italy, eventually arriving at a small town called Aversa, not all that far from Naples. This proved to be another transit camp (Campo P.G. 63) and I cannot recall how long we stayed there. All I recall is that it was summer and there were flies in their millions. The commandant of the camp was a small Italian lieutenant-colonel with a very short fuse. On one occasion when something upset him, he called a parade of all the officers in the camp: South African, British, some Australians, and a number of Indian Army officers. As he could speak no English, he harangued us in Italian, screaming and shouting, and punching the air with his fists. After about five minutes of this, he turned to his interpreter who said in English, “Gentlemen, the commandant is displeased with you.” We all burst out laughing, whereupon the commandant really went crazy, and finally stamped off the parade ground.

We were not very long at Aversa before we were moved once again, this time quite a long way up north to a town called Modena, presently famous as the birthplace of opera singer Pavarotti, and the place in which the Ferrari factory is situated. For us it was the place in which Campo P.G. 47 was located. P.G. stands for Prigioniero di Guerra: prisoners of war (POWs). The camp was some way out of town, and was built in the form of a square, with all the buildings on the sides of the square, with a very large expanse of open ground in the middle. Our accommodation was in the form of large bungalows, each holding a substantial number of officers.

POW sport at Campo 47.

We soon settled into a routine, which revolved around food, efforts to escape, and sport. As far as the latter was concerned, we laid out all sorts of sporting facilities on the open ground in the centre of the camp. One of our most popular sporting activities was softball, as it was so easy to organise and needed a minimum of equipment.

One of my closest friends in the camp was Les Payn from Natal, who was a brilliant cricket all-rounder and an especially good left-arm leg spinner. When he was captured at Tobruk, he had a cricket ball in his possession, which survived through to Aversa. During a routine search there, the Italians came across Les’s ball, about which they were highly suspicious and insisted upon cutting it open to see what he was concealing inside. Also when he was captured, he was wearing a Red Cross armband as he was in charge of African stretcher bearers (he spoke Zulu like a Zulu). His armband was to stand him in very good stead when a delegation from the International Red Cross visited the camp. They declared him a non-combatant and arranged that the Italians should repatriate him via Switzerland and the UK to South Africa. Back in the Union of South Africa, he went to see next-of-kin of POWs in our camp, and called on Molly (my wife) to tell her that I was fine. After the war, Les became a Springbok cricketer and remained my very good friend until he died in the eighties.

In between our sporting and other recreational activities—I also played a great deal of bridge—we dreamt of escaping and getting back to our units while the war was still on. We never considered that it could go on for another three years.

A tunnel is no easy thing to construct. . . or to conceal. You must start with a tunnel entrance, which must be in a building so that your activities are hidden from prying eyes, and where you can spot the approach of enemy sentries in time to close down tunnelling activity before they came upon it. Then your major problem is to get rid of the ‘spoil’: the earth that you excavate from the tunnel. You must keep the tunnel going in the right direction—easier said than done—or you may find it breaking out in the Italian commandant’s office! And finally, you have to contend with the technicalities of tunnelling such as ‘shoring up’ to prevent subsidence and ventilation as the tunnel increases in length. Digging a tunnel may take many months and then not be successful.

Italian campo entrance.

I was involved in two tunnels in Modena, which kept me busy for most of the time I spent in Campo P.G. 47. Both were eventually discovered before we had got very far. In the one case, the tunnel entrance was found during a routine search, despite it being very well concealed. In the other case, the spoil, which we distributed over the sports fields during the night, showed up a different colour in the light of day, alerting the Italians to the fact that a tunnel was under construction. They would then search for days until they found the entrance.

While we were busy with the second tunnel, I approached an air force friend, Jeff Morphew, to ask him whether he would care to join our tunnelling team. Much to my surprise, he turned the offer down. What I didn’t know then was that Jeff and a friend of his were on the brink of a brilliant escape, which for security reasons he dared not tell anyone else about. Jeff and his friend were both small men. They had made themselves Italian soldiers’ uniforms, complete with wooden rifles, which looked just like the real thing. When the time came, their plan was to wait for dusk when the day guards inside the camp finished their shift and marched out of the front entrance to the compound. They would fall in behind the single file of departing guards and march out with them, hoping that there was no-one counting the number of guards who marched out—as it turned out, no-one was.

Jeff and his friend Coelgees were taken to be genuine Italian soldiers, and once out of the POW compound, they laid up until it was completely dark and then walked out of Campo P.G. 47 altogether. They then changed out of their Italian uniforms into civilian dress, and bought tickets at the local railway station to get as far away from Modena as possible. Later, while they were en route to the Swiss border, they became separated and Coelgees was recaptured. Jeff, however, made it into Switzerland, where he met the girl he was eventually to marry. From there he was helped by the French underground to cross occupied France by train, thence through Spain to Gibraltar, which remained in British hands throughout the war. From Gibraltar, he was flown back to England where he was seconded to the RAF, finding himself back on operations against Germany.

Red Cross food parcel contents.

Probably the subject nearest the hearts of all POWs was food, as this was usually the most pressing problem. The food provided by our captors was never sufficient but fortunately, for us, the International Red Cross was a wonderful organisation that looked after prisoners of war of whatever nationality and wherever they were.

When everything was going well, we would receive a weekly food parcel from the Red Cross, with such wonderful delicacies as ‘Klim’ (powdered milk), condensed milk, biscuits, jam, ‘Spam’ (American tinned meat), sugar and tea, etc. When things were not going well, the Italians—and later the Germans—would withhold the Red Cross parcels in order to punish us.

It was virtually impossible to live on the food provided by our captors, which usually consisted of a couple of slices of dry bread and a bowl of watery ‘soup’ per day. Now and again, we might be given a couple of shrivelled potatoes, or a piece of some ghastly vegetable called kohlrabi; also known as turnip-cabbage. There were also long periods when no Red Cross parcels could be delivered to the camps. During these periods, we really knew what hunger pangs meant.

Now, some fifty or more years after the war, it is difficult to recall just how hungry one was most of the time, but I do know that even when the supply of Red Cross parcels was satisfactory, one was still perpetually hungry. It was not unknown for some POWs to give promissory notes for up to £100—to be paid after the war—for the purchase of a Red Cross parcel.

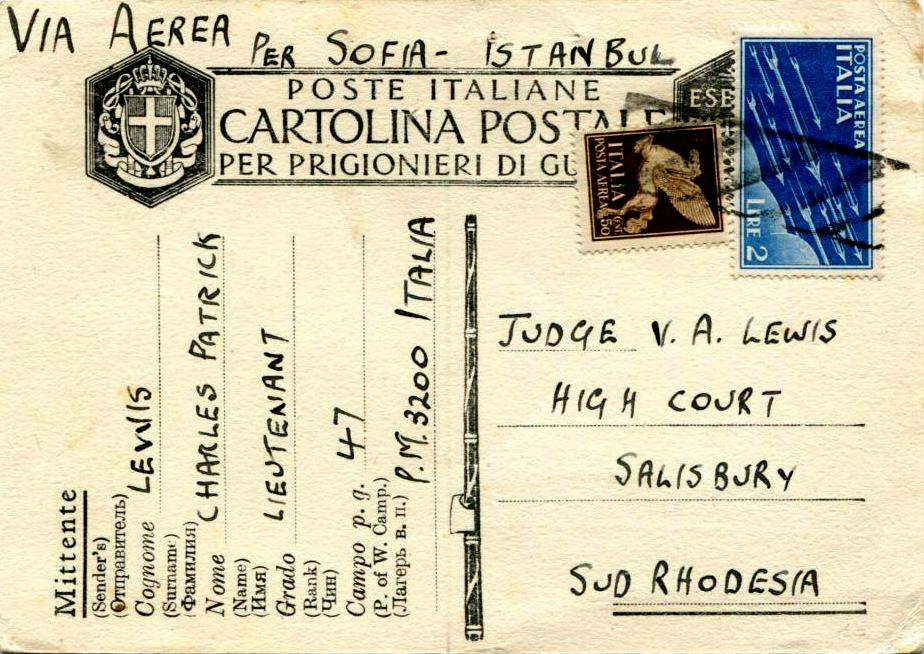

A Rhodesian POW’s ‘letter-card’ from Campo 47.

As POWs, we were allowed to write only one letter-card a month to our next-of-kin, and it wasn’t until we got to Modena that we were given this privilege, so it was a couple of months before Molly learned that she still had a husband after all. Whatever we wrote was subject to censorship by the Italian military authorities, so there wasn’t much that we could say about how we really were and what we really felt. Nevertheless, it was a lifeline to which we clung tenuously, as it was our only link with home.

Despite being locked up and isolated from the outside world, we were always aware of the progress of the war. Every camp had a clandestine radio receiver, which listened in to the news bulletins from the BBC. We also got an occasional newspaper into the camp from ‘friendly’ guards, so we knew what was going on in Italy and indeed the rest of the world.

The year 1942 passed painfully slowly for us, but we knew that the tide had turned with the battle of El Alamein fought in the Western Desert in North Africa in October, between the British 8th Army under General Montgomery and the German Afrika Korps under Field Marshal Rommel. Rommel’s drive towards Cairo had been stopped at the Alamein line, and then turned round after the Battle of El Alamein. The Afrika Korps and their Italian allies were soundly defeated. They started a withdrawal to the west, which would eventually lead to their being forced out of Africa and back, firstly to the island of Sicily, and then on to the mainland of Europe. The last battle on African soil was fought on 12th May 1943, heralding the end of the desert war.

Then came the Allied invasion of Sicily. The writing was on the wall for the Italian armed forces. The Fascist leader of Italy, Benito Mussolini, was driven from office in July 1943.

We began to get very excited when Allied forces entered Italy from the south, and as they began to move northwards with the intention of driving the Axis forces out of Italy altogether. At about this time, the Italian component of the Axis forces, realising that the war was effectively over for them, capitulated, leaving only the German armed forces to confront the advancing Allies, so we believed that it would not be very long before our camp was overrun and we would be released. Regrettably, I cannot now recall the dates on which things happened. I used to have a POW log in which I recorded the events that governed my life in those days, but this disappeared when I was living in Potchefstroom from 1949 to 1951.

It must have been August 1943 when it became apparent that very shortly our POW camp would cease to be guarded by the Italians. It was our hope that the Allied forces would overrun our camp and set us free. However, the Germans had dug themselves in on various defensive lines across Italy, effectively holding up the progress of Allied forces. The British and American armies were trying to move up from the south of Italy to the north, into what Churchill referred to as “the soft underbelly of Europe”. So much so, that when the Italian capitulation took place and the guards disappeared from Campo P.G. 47, their place was taken immediately by the Germans, who entered the camp with the express intention of moving all the POWs out and transferring them to Germany.

Many of us in the camp had decided to get out the moment the Italian guards left. We were ready to do so, but then a message was received, via our clandestine camp radio, from the British HQ in Italy, to the effect that we should stay where we were and not leave the camp under any circumstances until we were relieved by the British forces. We were all summoned on to the parade ground and addressed by the senior officer in the camp, who was a New Zealand lieutenant-colonel. He said that he had received this instruction from the British HQ in Italy and advised no-one to disobey the instruction. Subsequently, when he realised that the great majority of the officers in Campo P.G. 47 had been moved to Germany because of following his advice, he very sadly committed suicide. The next morning, the Italian guards disappeared and the Germans marched in.

The following day we were marched out of the camp, and down to the Modena railway station where we were loaded into cattle trucks for the long train journey to Germany.

On the railway platform, I witnessed one of the most horrible things I have ever seen. Italian civilians were also being sent to Germany as labourers. One young Italian lad was embracing a woman who presumably was his mother. She was crying and holding on to him, while a young German officer was yelling at him to get on to the train. The more the German yelled, the more the woman cried and clung to the young man. Eventually the German officer pulled out his Luger pistol, and without further ado, shot the young Italian dead in his mother’s arms.

When all the POW officers were loaded into the cattle trucks, the doors were bolted from the outside, and the train moved off. We had no water, there were no toilet facilities, and we were crowded to the point where no-one could lie down. It was hot and airless. We had no idea how long we would be incarcerated in the trucks.

(To be continued. . . Germany, Stalag Luft III, the Great Escape)