BOVENPLAAS AND THE BOYHOOD OF JAN SMUTS

Jan Christiaan Smuts first went to school at the age of 12. Before then, his teachers were his parents, their farmworkers, and Mother Nature …

By Greig Stewart

Boplaas: The simple thatched house where Jan Smuts was born. Photo: Michelle McCann.

Jan Smuts’s extraordinary life was rooted in the rich, dark soil and ancient grey rock of the Swartland, on the farm Ongegund. The name is difficult to translate. Literally it means ‘un-fertile’ but could be read as ‘not quite what we expected’, or perhaps simply ‘begrudged’.[1] The Smuts family referred to their portion of the farm as ‘Boplaas’, which had a much more optimistic ring. For all that’s in a name, the land provided the Smuts family with a comfortable living for five generations, and in turn built on a long farming heritage.

The Smuts family were amongst the earliest European settlers. The stamvader (progenitor) was Michiel Cornelisz(oon), who arrived from Middleburg in Holland at what was then called De Cabo between 1695 and 1698, just 45 years after Jan van Riebeek established a victualling station for the Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie. The first record of a Smuts farming was in July 1700, when Michiel’s third son, Michiel Cornelis, took transfer of land in ‘Table Valley’. By 1786 the Smuts’s had established themselves in the Swartland, 15 km north of Malmesbury on the Piquetberg road, with third-generation Michiel Smuts being granted the right to occupy with his cattle ‘de plaats genaamt Zoutfontein gelegen in ‘t Swartland’ on 16 April 1786.[2]

Some thirty years later, on 15 October 1813, Michiel’s third son, Michiel Nicolaas Smuts, took transfer of Ongegund, 8km to the east of Zoutfontein, at the northern end of the mountain known as Riebeek’s Kasteel (now the Kasteelberg) – so named because from its peak one could see the castle on the shores of Table Bay, 70 km to the south.[3] The farm was the typical 60 morgen freehold farm of the Company period, for which he paid a Mr P. Burger 533 rijksdaalders – about R210 000 today. On 10 June 1818, Michiel was granted an additional 1 472 morgen of quitrent land, and in 1831 a further 182 morgen, making a total of 1 712 morgen. Ongegund was by then one of the most substantial farms in the district.[4]

A tale of two brothers

After Michiel Nicolaas died aged 60 on 18 October 1848, this large farm was left jointly to his five sons. One, Marthinus, died in 1856. Another brother, Josias, wanted to be on his own, and roughly one fifth of the farm, 276 morgen in extent, was cut off to form the new farm De Gift. Over the following years the two eldest brothers, Michiel, (Jan Smuts’s grandfather) and Pieter van der Byl, bought up the shares of Marthinus’s widow and of Daniel, the fifth brother, and thus became joint owners of the remaining 1 438 morgen of the original farm.[5]

Michiel farmed the southernmost portion closest to the village of Riebeek-Wes, the high ground on the flank of the Kasteelberg. They called it ‘Bovenplaas’, and later simply ‘Boplaas’.[6] At the age of 25, Michiel married 19-year-old Adriana Martha (née Van Aarde) on 13 May 1838, and they moved into a snug house in a hollow at the foot of the Kasteelberg, sheltered from the south-westerly wind, shaded from the north sun by huge bluegum trees, and well-watered by a strong spring.

The voorkamer: Many people donated period furniture when the house was restored in 1986.

Photo: Michelle McCann.

Little is known about the origins of the house, other than that it was probably built by Michiel ahead of his marriage to Adriana.[7] Some sources suggest it was converted from an existing barn, and the long, narrow building does have that appearance.[8] Yet it was a substantial building, the massive walls of stone blocks cemented by clay and faced on the inside with sunbaked brick pierced by square, deep-set windows that were leaded and shuttered. It consisted of a main bedroom and a voorkamer – both the width of the house – a smaller bedroom off the voorkamer, a large kitchen with an open fireplace and a huge bread oven that protruded into the pantry and storeroom behind. The building was roofed with reed thatch pitched over a loft, accessed via an outer stone-built staircase. The woodwork was carefully crafted; the doors solid and well-hung, and the wide yellow-wood plans of the floor placed and fitted ‘close and true’.[9] A typical Swartland farmhouse of the time, it had none of the gabled grace of Constantia or Stellenbosch. It was a sturdy, simple, comfortable house, cool in the summer and warm in winter. It served the newlyweds well.

The main bedroom. The photos above the bed are of Jacobus and Catharina Smuts, parents of Jan Smuts. Photo: Michelle McCann.

Sometime in the early 1860s, as their family grew – Michiel and Adriana had eight children, four daughters and four sons – they built a much bigger homestead some 20 metres to the north of the existing house.[10] This was a roomy H-shaped structure, built of stone and roofed with corrugated iron. It had deep, shuttered windows and ‘broekie-lace’ ironmongery supporting a veranda, roofed with the bullnose corrugated iron popular at the time.

The talented Mr Smuts, MLA

Their second son, Jacobus Abraham, farmed together with his father on Bovenplaats. Jacobus was a hard-working, intelligent farmer who became a pillar of his church and took a leading part in the social and political life of the district. These qualities led to him being elected in 1898 to the Parliament of the Cape of Good Hope for ‘Onze’ Jan Hofmeyr’s Afrikander Bond as the member for Malmesbury, and in the legislative assembly he steadfastly supported his party ‘without any speechifying’. In private, he was a lively talker with firm opinions, so much so that ‘Mr Smuts, M.L.A.’ came to the attention of British military intelligence very early in the South African War, long before his son had achieved fame on his notorious expedition into the Colony. All that was in the future when Jacobus, a month ahead of his 21st birthday, had married 21-year-old Catharina Petronella Gerhardina De Vries, on 6 March 1866.

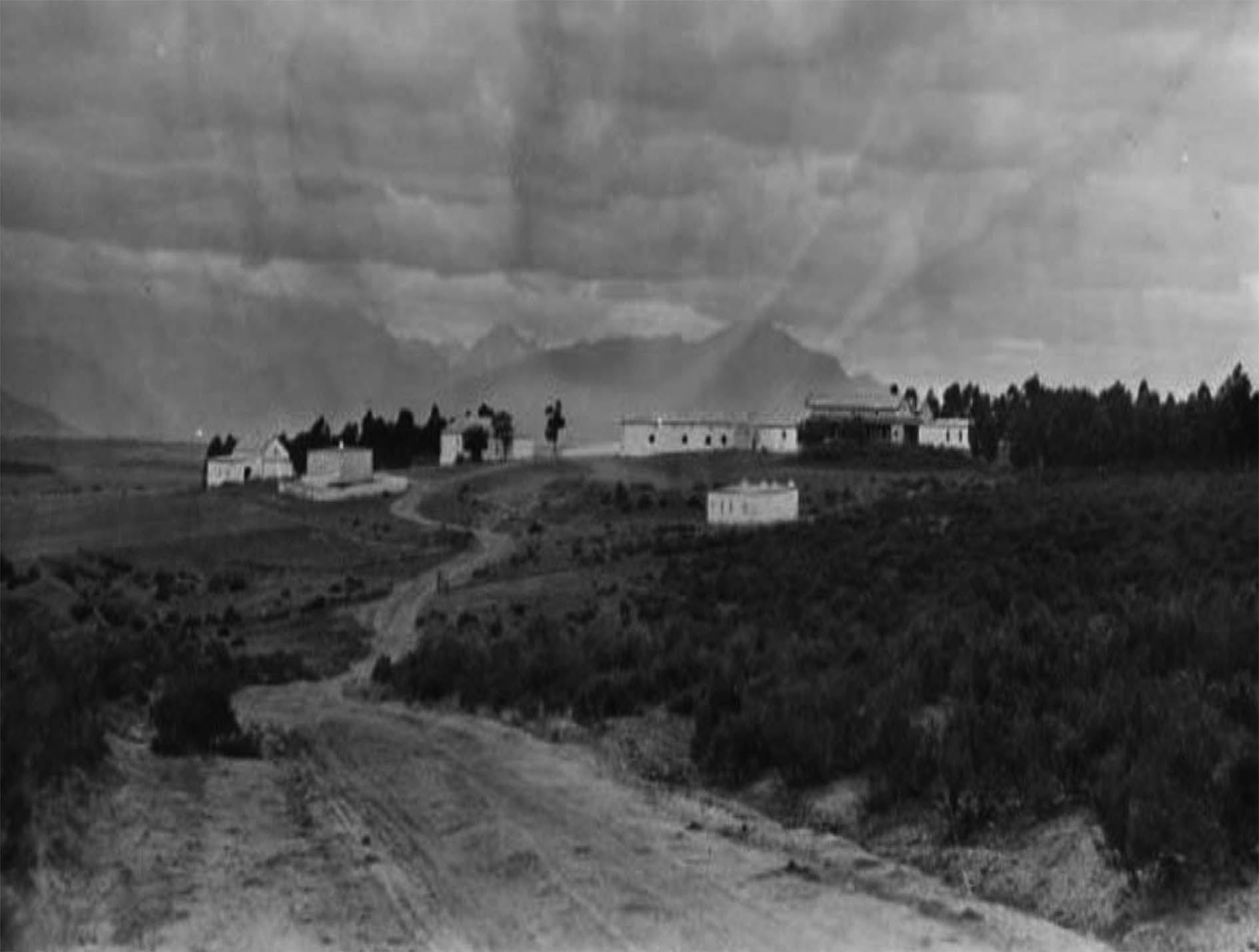

The ‘big house’, built by Michiel and Adriana Smuts, demolished in the 1980s. Photo: Riebeek Valley Museum.

Catharina, or Cato as she was known to family and friends, came of a Dutch-French family that valued education highly. After attending the village school in her hometown of Worcester, her father, Jan Christiaan de Vries, then sent her to one Miss Syfret’s school in Cape Town, ‘where she acquired accomplishments such as pianoforte and French’. When her elder brother, Boudewyn de Vries, returned from six years’ study at the theological faculty at Utrecht University, she accompanied him to his posting to Riebeek-Wes. Here she met her husband. This ‘fine and learned lady soon proved herself as able a farmer’s wife as her neighbours, without ever losing her own individual depth and delicacy of perception’.[11]

A sovereign day

They lost no time in starting a family, and Michiel was born on 29 December 1866. They then waited a while to have another child. Their second son, Jan Christiaan Smuts, was born on 24 May 1870, in the autumn when the first of the winter rains were sweeping in from the north-west, bringing the winter wheat out in a soft emerald carpet across the fields. He was christened after his maternal grandfather, Jan Christian de Vries.[12] The day had some significance in the Cape Colony, for it was also Queen Victoria’s 51st birthday, an anniversary that after her death in 1901 would become Empire Day and would, forty years after his birth and at the birth of the Union of South Africa, become a deeply significant one for Jan Smuts.

The birthplace: The small room where Jan Smuts was apparently born. Photo: Michelle McCann.

As was the custom, only the eldest son, Michiel, went to school to be ‘geleerd’, that is, to be educated beyond the basics so that he might enter the church or one of the professions, at Mr Theunis Christoffel Stoffberg’s ‘Ark’ in Riebeek-Wes. Cato gave her children an excellent home education. She had a well-filled bookcase and ‘took the children through a little book called Step by Step, which gave them the rudiments of English grammar’.[13] She had a powerful influence on her children, who remembered her with feelings of gratitude and love, almost of reverence’.[14] Cato was certainly thought by her contemporaries to be a most diligent mother.

An unsympathetic – indeed, insufferably patronising – biographer in the late 1930s described Jan’s childhood as ‘dirty, untidy and unwashed, dressed in ragged clothes, a blanket round his shoulders’.[15] That was not so. ‘The little boys were dressed in clean blouses of white or blue with dark pantaloons and velskoen. They helped their father with the farming, and because their skin was so white their mother made them put on their sunbonnets to shelter them from the heat of the sun. No, Jan Smuts and his brothers and little sisters never grew up in rags and tatters [het nie in flenters, tatters groot geword nie].’[16]

A sickly boy?

There were plenty of these misconceptions about the boy. Smuts was often described as a weak and sickly child, but this was not the view of his younger brother, Boudewyn (‘Bool’) Smuts. He described Smuts as ‘delicate’ (tingerig) not sickly (sieklik).[17] His son commented that ‘though not a weak or sickly boy, his constitution was not robust’.[18] However frail and delicate he may have appeared in his youth, he certainly was not in adulthood. He did not succumb to the typhoid – all too common in rural environments where cows were kept – that carried off his elder brother, Michiel, who died at the age of sixteen, in 1882. Certainly, there was nothing frail about the man who suffered the privations of the South African War, so well described by his protégé Denys Reitz, and who strode up Table Mountain well into his 70s.[19]

The young Jan apparently showed little of the omnivorous intellect of his later life. He was content to be immersed in the natural wonders around him. When he was old enough, he minded the klein goed – the fowls and pigs of the farmyard.[20] ‘He was left a fairly free hand to do as he wished, providing he carried out the prescribed family duties of tending his father’s flocks.’ He learned much of the glorious rich world of the farm and surrounds from a ‘philosophical old farm hand, the wizened Hottentot Adam’, who taught him his people’s ancient lore of the land, and the skills needed to survive and prosper in it.[21]

On Michiel’s death in 1868 Jacobus had sold his half-share of the farm to his uncle, Pieter van der Byl Smuts, who thus became the sole owner. Jacobus lived comfortably and farmed profitably on his uncle’s land – he sold wine and milled wheat for his neighbours – but his uncle had seven sons of his own, five of whom were at one stage accommodated on Ongegund and the adjoining farm, Middelpos.[22] Those sons now naturally wanted to farm in their own right, as now did Jacobus, who could afford to.

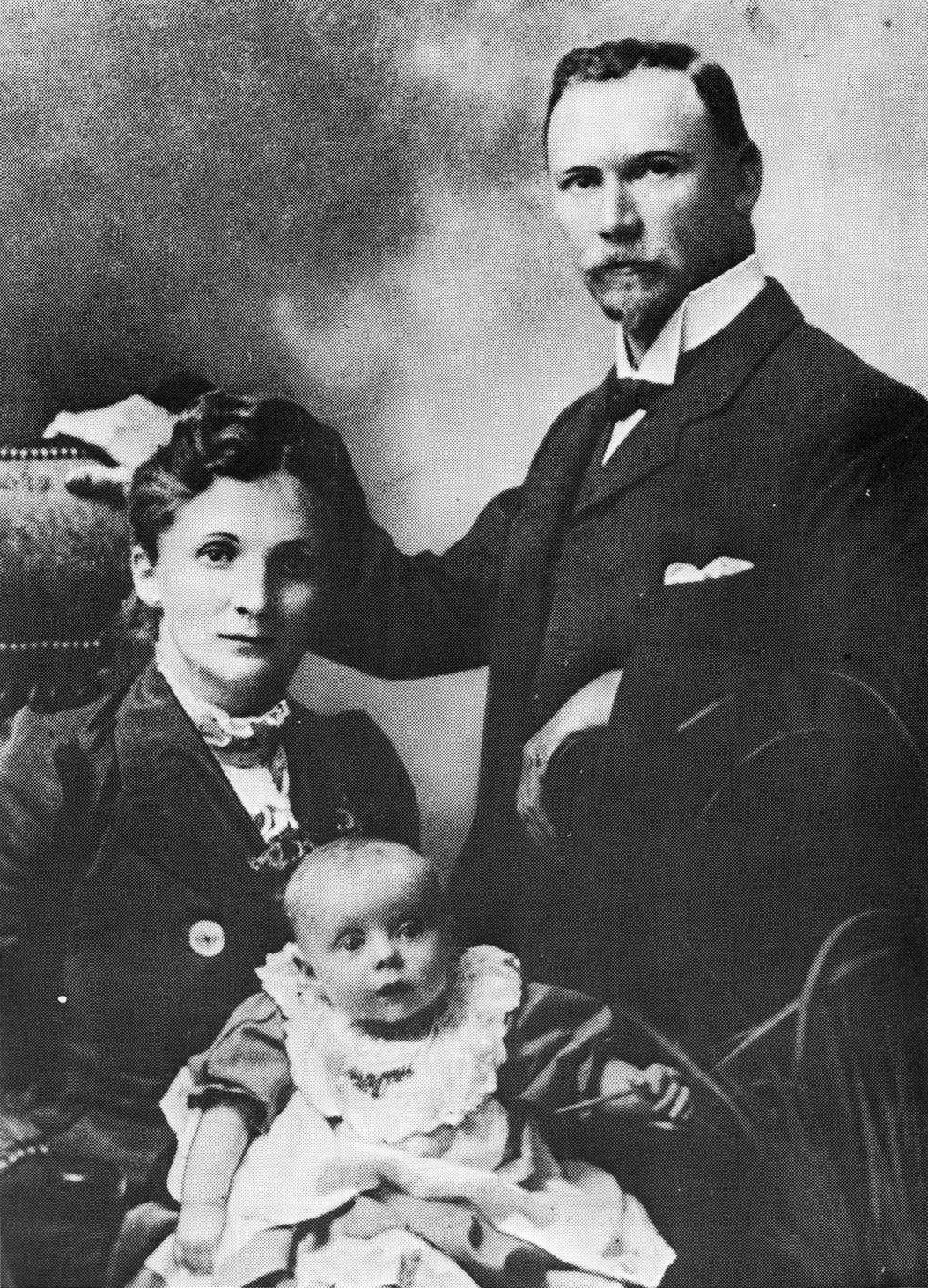

An early family portrait: Jacobus and Cato with, front from left, Maria Magdalena (1872 – 1923), Jan Christiaan (1870 – 1950), and Michiel (1886 – 1882). Image: University of Cape Town Smuts Collection.

Widening horizons

Klipfontein, circa 1924. Source International Harvester Company, courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society.

In early 1876, Jacobus bought his own farm, Klipfontein, some 20 km north of Riebeek-Wes, for £400 and they moved there just before Jan turned six. The red-shuttered farmhouse there was a larger and more modern building than the old homestead at Boplaas, if not as old, quaint and attractive. It stood on a rise and looked out over the broad valley of the Berg River and the Winterhoek mountains in the distance and sat foursquare in an eternity of land and sky.[23] It was here that Jan roamed the farm, ‘a small speck in an immense landscape’ and where his love of nature was cemented. It was here that he began to feel those perceptions of the natural world and those intimations of his own self which afterwards took shape in his thought, speech and writing.’[24] He would write, many years later:

‘I saw the vast line of blue Winterhoek mountains stretched out before Klipfontein with a beauty of colour and line and a majesty which made it even more to me than in the days of youthful romance in the far past. I could not think of anything more lovely in my long experience of scenery. And I blessed my good fortune in having been privileged to grow up in such surroundings and with home associations which remain an unforgettable memory. The beauty of home life was fully matched by the beauty of the world around me’.[25]

Scaling many summits

On the death of his elder brother in 1882, Jan went to school – at the age of 12 – and lived at ‘The Ark’ in Riebeek-Wes, the house schoolmaster Stoffberg’s wife, Francina, kept for the boarders. He was put into the lowest class, but within a week or two was promoted to a higher one. He devoured the contents of the headmaster’s library, regardless of whether his reading related to the curriculum or not. Within a year, he was vying for top honours in class with Cinie, the daughter of their family friends, the Malans of Allesveloren.[26] Jan would later instruct her younger brother, Daniël Francois Malan, at Sunday school. Mr Stoffberg, who thought that Jan Smuts was one of the most brilliant pupils he had ever taught and the hardest-working boy he had ever met, called Smuts ‘a Maxim gun to Malan’s Long Tom’.[27]

The Religion of the Mountain. Smuts on the Kasteelberg, above Riebeek West. He is sitting on an outcrop know as Pulpit Rock, on his uncle Josias’s farm De Gift. Undated, photographer unknown.

It was here that Jan climbed his first mountain, the Kasteelberg behind the village. On the summit he had ‘a strange, intense experience; he did not describe it explicitly, but seemingly it had a mystic tinge’.[28] His lifelong love of mountains would be poignantly expressed in a 1923 address to the Mountain Club during the unveiling of a memorial to members who had fallen in the 1st World War on top of Table Mountain (see ‘The Religion of the Mountain’).

After three years at school Jan took ninth place in the Colony’s elementary examination, and in the following year he took the second place in the School Higher examination (the winning boy had been schooled for seven years).[29] In July 1887, he went to Stellenbosch to study for his matriculation – gaining a first class pass – and where he would meet Sybella Margaretha Krige, or Isie, as everybody called her. He had stepped into manhood.

A singular academic career

During his four years in Stellenbosch, he would return to Klipfontein in the holidays, until he took his double first in Science and Arts, and was awarded the Ebden scholarship to Cambridge, which he entered in October 1891. He would return in June 1895, having earned a first in both parts of the law tripos – a feat unequalled at that time – won the coveted George Long prize in Roman Law and Jurisprudence, read philosophy and German literature, written an unpublished work on the poet Walt Whitman and an outline of his later work on what he would call ‘holism’. He was admitted to the Middle Temple as a barrister in December 1894, and Christ’s College offered him a fellowship in law, but he turned it down and went home.[30]

Sybella (‘Isie’) and Jan Smuts, with daughter Susanna Johanna (‘Santa’), in late 1903. Courtesy Cape Times.

He opened a legal practice, but had little success, and turned to journalism and politics. He joined the Afrikaner Bond, for which his father would later become an MP. He met the premier of the Cape Colony, Cecil John Rhodes, whose ideas on the shared interests of the two white ‘Teutonic’ tribes the Bond supported. He became a devotee and delivered a passionate speech on Rhodes’s behalf in Kimberley on 29 October 1895. The speech ‘made him widely known as a rising young politician’, but his friend Olive Schreiner thought him ‘very earnest and sincere, but he doesn’t know Rhodes![31]

Indeed, he did not know Rhodes. Few then knew the depths of his recklessness. The Jameson Raid at the end of that year broke his faith in the ‘Colossus’. In search of a fresh alternative, he applied for, but did not get, a lectureship at the South African College. How different the world would be if Jan Smuts had entered academia! Jan then turned his eyes north. And in January he moved to Johannesburg and started earning enough of a living at the Transvaal Bar to marry Isie in April. In June 1898 he was appointed as state attorney to the Transvaal.

Eighteen months later South Africa descended into war. As Thomas Packenham pithily put it: ‘The war declared by the Boers on 11 October 1899 gave the British, in Kipling’s famous phrase, ‘no end of a lesson’. The British public expected it to be over by Christmas. It proved to be the longest (two and three-quarter years), the costliest (over £200 million), the bloodiest (at least twenty-two thousand British, twenty-five thousand Boer and twelve thousand African lives) and the most humiliating war for Britain between 1815 and 1914.’[32]

The state attorney was one of the first at the front, commanding a supply train bring a Long Tom from the Pretoria first to the Natal border.[33] Six months later he would oversee that transfer of the last of the Transvaal’s gold reserves out of Pretoria ahead of the advancing Lord Roberts. He bade farewell to his wife and children and took to the field, first with De la Rey in the Magaliesberg, and then into the Cape Colony with 340 men. He would end the war as an admired general, and one of the leaders of the Boers. The closest he would come to Klipfontein was when, during his epic incursion into the Cape so well described by Reitz, his brother-in-law, Uys Krige, ‘penetrated as far as Malmesbury, and brought back a large sum of money for the use of the commando from General Smuts’s father.’[34]

The fate of the farms

Klipfontein remained the prosperous family farm, and after the death of his father, Jacobus, on 25 August 1914, passed to Jan’s younger brother, Boudewyn (‘Bool’) Smuts, who lived there until his death in 1953. Jan Smuts’s birthplace had a livelier time.

After Pieter van der Byl Smuts died, Ongegund was jointly owned and farmed by two of his sons, Pieter and Albertus, until the death of the former in 1908. It was then divided between Pieter’s widow and Albertus; the northern half of the farm being named Delectus. The original Ongegund is ‘thus divided, like Caesar’s Gaul, into three parts: the farms De Gift, Ongegund and Delectus’.[35]

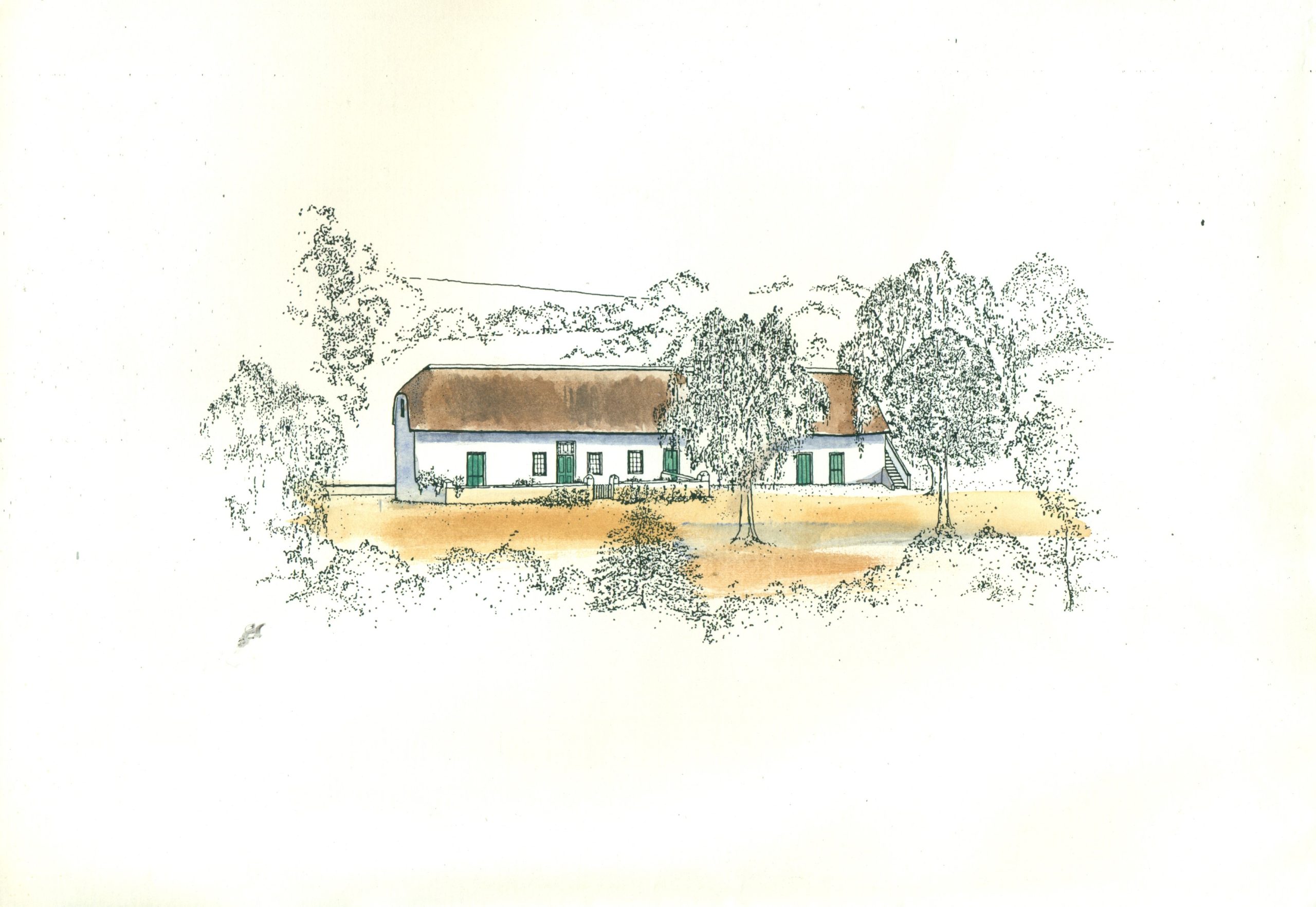

Sketch of Boplaas, circa 1986. Courtesy of Gabriël Fagan Architects.

The Boplaas portion passed to Pieter van der Byl Smuts, who sold it in 1946 to the Cape Portland Cement Company. In 1940 geologists had discovered that Ongegund had one of the biggest and best limestone deposits in the province. Pieter van der Byl insisted on various conditions regarding the preservation of the farmhouses and the family graveyard, which the chairman of the company, Sir Alfred Hennessy, endorsed.[36]

In 1955 the Board for National Monuments put up a bronze plaque on the house where Smuts was born, and in 1975 it was proclaimed a national monument.[37] By then both the ‘old’ house and the ‘new’ house, though inhabited, were in disrepair. Pretoria Portland Cement (PPC), which had acquired Cape Portland, had started a renovation in 1968, and appointed an architect. However, the scheme fell apart, and the trust fund set up to finance it was wound up on 1980.[38] In 1984 PPC chairman, George Bulterman, commissioned renowned architect Gabriël ‘Gawie’ Fagan to restore the buildings. Fagan and his wife Gwen were known for the restoration of Church Street in Tulbagh after the 1969 earthquake, and of many grand houses such as Boschendal, Buitenverwachting, Genadendal, Rust en Vrede, and Tuynhuis.

It was decided to demolish the ‘new’ house, as it was in disrepair and had no particular architectural or historic merit and make the best use of the funding provided by PPC to restore Smuts’ birthplace. The restoration was meticulous, and many people donated furniture, artefacts and pictures to round out a superb recreation of the home as it would have been in Smuts’s childhood. The work was completed in 1986, and inaugurated by the Minister of National Education, FW de Klerk, on 20 May.

The museum, maintained and preserved by PPC on the edge of its working plant, is well-worth a visit. Walking through the house and the grounds, one can almost imagine the simple, hard but fulfilling life of a Swartland farm 150 years ago, and a pale, slender child in a pinafore and sunbonnet trailing behind the chickens and geese, lost in contemplation of the rhythms of the season and the riches of the land. And none of it begrudged.

Sidebar: The Smuts Birthplace Museum

Hours: 10.00-16.00 on Wednesdays, Fridays and Saturdays

How to get there: 2.2 km north of Riebeek West on the R311, turn right at the PPC Riebeeck entrance and follow the signs.

GPS co-ordinates: -33.322, 18.849

More info and images: https://www.riebeekvalleytourism.co.za/smuts-museum/

Sidebar: The Religion of the Mountain

“The Mountain is not merely something externally sublime. It has a great historical and spiritual meaning for us. It stands for us as the ladder of life. Nay, more, it is the great ladder of the soul, and in a curious way the source of religion. From it came the Law, from it came the Gospel in the Sermon on the Mount. We may truly say that the highest religion is the Religion of the Mountain.

What is that religion? When we reach the mountain summits we leave behind us all the things that weigh heavily down below on our body and our spirit. We leave behind a feeling of weakness and depression; we feel a new freedom, a great exhilaration, an exaltation of the body no less than of the spirit. We feel a great joy.

The Religion of the Mountain is the religion of joy, of the release of the soul from the things that weigh it down and fill it with a sense of weariness, sorrow and defeat. The religion of joy realises the freedom of the soul, the soul’s kinship to the great creative spirit, and its dominance over all the things of sense. As the body has escaped from the over-weight and depression of the sea, so the soul must be released from all sense of weariness, weakness and depression arising from the fret, worry and friction of our daily lives. We must feel that we are above it all, that the soul is essentially free, and in freedom realises the joy of living. And when the feeling of lassitude and depression and the sense of defeat advances upon us, we must repel it and maintain an equal and cheerful temper.

We must fill our daily lives with the spirit of joy and delight. We must carry this spirit into our daily lives and tasks. We must perform our work not grudgingly and as a burden imposed upon, but in a spirit of cheerfulness, goodwill and delight in it. Not only on the mountain summits of life, not only on the heights of success and achievement, but down in the deep valleys of drudgery, of anxiety and defeat, we must cultivate the great spirit of joyous freedom and upliftment of the soul.

We must practise the Religion of the Mountain down in the valleys also.

This may sound like a hard doctrine, and it may be that only after years of practice are we able to triumph in spirit over the things that weigh and drag us down. But it is the nature of the soul, as of all life, to rise, to overcome, and finally attain complete freedom and happiness. And if we consistently practise the Religion of the Mountain we must succeed in the end. To this great end Nature will co-operate with the soul.

The mountains uphold us, and the stars beckon to us. The mountains of our lovely land will make a constant appeal to us to live the higher life of joy and freedom. Table Mountain will preach this great gospel to the myriads of toilers in the valley below. And those who, whether members of the Mountain Club or not, make a habit of ascending her beautiful slopes in their free moments, will reap a rich reward not only in bodily health and strength, but also in an inner freedom and purity, in a habitual spirit of delight, which will be the crowning glory of their lives.

May I express the hope that in the years to come this memorial will draw myriads who live down below to breathe the purer air and become better men and women. Their spirits will join with those up here, and it will make us all purer and nobler in spirit and better citizens of the country.”

– Jan Smuts’s address on 25th February 1923 during the unveiling of a memorial on top of Table Mountain to members of the Mountain Club who had fallen in the 1st World War.

Acknowledgements, and about the author

I am indebted to John Wilson-Harris of Gabriël Fagan Architects for access to his archives of the 1986 restoration; to Chris Murphy of the Riebeek Valley Museum for images, and to Michelle McCann (https://www.facebook.com/michellemccannphotography/) for her superb photographs. I wrote this because I am interested in Jan Smuts, and live at Ongegund, near his birthplace. Errors and omissions are my own, and I would welcome corrections and additional information. Greig Stewart <greig@stewart.org.za>.

Images

Jacobus and Catharina Smuts with front from left, Maria Magdalena (1872 – 1923), Jan Christiaan (1870 – 1950), and Michiel (1886 – 1882). University of Cape Town.

The ‘big house’ built by Michiel and Adriana, Jan Smuts’s grandparents. It was demolished in the 1980s.

- Hancock, WK (William Keith). Smuts: The Sanguine Years 1870-1919. Cambridge University Press, 1962. p. 4. The Ongegund farm was apparently named by the first owner, Andries van der Heide, in 1708 – Cape Archives and Records Service. OSG Vol. 2, 1 Nov 1708, S.G. Dgm No. 26/1708. ↑

- ‘Factual errors in Hancock’s biography of Smuts’. Unpublished, partial, undated, anonymous but authoritative document in the records of the 1986 renovation of Boplaas by Gawie Fagan (15 November 1925 – 13 September 2020). Possibly written by Pieter Smuts. Courtesy of John Wilson-Harris of Gabriël Fagan Architects. Hereafter ‘Fagan collection’. ↑

- De Kock, Willem Johannes. (ed). Dictionary of South African Biography. Volume I. National Council for Social Research, Pretoria, 1968. pp. 737-758. ↑

- A Dutch morgen is equivalent to two acres, or 0.8 hectare. Ongegund was thus 3 424 acres, or 1 385 ha. – Fagan collection. 533 rijksdaalders would be equivalent to about R210 000 today – www.numismaster.com ↑

- Fagan collection. ↑

- The transfer was made on 10 June 1818. It was called, in Dutch, ‘Bovenplatz’. Hancock. p 562. It was bought from a P Burger for 533 riksaalders – Pretoria Portland Cement Co. reprint from SA Panorama, August 1988. ↑

- Hancock was ‘greatly indebted to Mr V. C. H. R. Brereton, who in his profession as surveyor is familiar with Ongegund, for investigating its history from 1708 to the present day and writing a full account for my use’. Unfortunately, this document could not be found in the Keith Hancock Collection at the National Library of Australia. ↑

- The Smuts Cottage: Birthplace of Jan Christian Smuts, Pamphlet by Pretoria Portland Cement. 1986. ↑

- Hancock. p 5. ↑

- Michael and Adriana’s children: Maria Jacoba Magdalena (1839-1924), Gertruida Anna (1841-?), Michiel Nicolas (1843-1904), Jacobus Abraham (1845-1914), Pieter Van Der Byl (1847-1910), Izak Johannes Jacobus (1849-1926), Adriana Martha Christina (1851-1892), and Susanna Maria Jakoba (1853-1904) ↑

- Hancock. pp 6-7. ↑

- Jan Christiaan was the name recorded on his birth certificate. His son said ‘Like his grandfather, he spelt Christian with one “a”.’ – Hancock, p 3, and Smuts, Jan. Jan Christian Smuts. Cassell & Company, 1952. p 25. To add further to the flexibility of names, Jan Christian de Vries’s name in the Dutch Reformed Church baptismal register at Stellenbosch on 13 August 1815 is ‘Cristiaan’. Dutch Reformed Church Registers, 1660-1994. Western Cape Government Archives and Records Service. ↑

- Hancock. p 8. ↑

- ibid. pp 6-7. ↑

- Armstrong, Harold Courtenay. Grey Steel: J C Smuts – A Study in Arrogance. Meuthen & Co., London, 1939. p. 7. ↑

- Hancock. p 6. ↑

- ibid. p 563. ↑

- Smuts, Jan. Jan Christian Smuts, by his son. Cassell & Co, Cape Town, 1952. p. 11. ↑

- Reitz, Denys. Commando – Adrift on the Open Veld trilogy. Stormberg Publishers, Cape Town. 2000. ↑

- His siblings were: Michiel (1866–1882), Maria Magdalena (1872–1923), Jacobus Abraham (1874–1939), Boudewyn de Vries (1876–1953), Adriana Martha (1882–1952), and Pieter van der Bijl (1884–1908). ↑

- Smuts, Jan. p. 12. ↑

- Fagan collection. ↑

- ibid. p. 15. ↑

- Hancock. pp 9-10. ↑

- ibid. p 7. ↑

- Koorts, Lindie. DF Malan and the rise of Afrikaner nationalism. Tafelberg Publishers, Cape Town 2014. p. 4. ↑

- Hancock. pp 11-12. In one of those strange twists of history, in 1915 Theunis Stoffberg resigned from the position of Transvaal inspector of schools – to which he had been appointed by Smuts as Minister of Education – to contest the Rustenberg constituency for the National Party. He lost to Louis Botha and Smuts’s South African Party candidate. – Levy, Naphtali. Jan Smuts: Being a Character Sketch of Gen. the Hon. J.C. Smuts, K.C., M.L.A., Minister of Defence, Union of South Africa. Longman, Green & Company, London, 1917. p. 4. ↑

- Hancock, p. 13. The draft of a speech dated 30 May 1950. It was to have been a ‘thank you’ speech to Cape Town for its proposed present of a cottage on Table Mountain, but he fell ill before he could deliver it. He died four months later, on 11 September 1950. ↑

- Hancock. p 7. ↑

- Smuts, Jan. Walt Whitman: A Study in the Evolution of Personality. Wayne State University Press, 1973. ↑

- Hancock. pp. 56-58 ↑

- Pakenham, Thomas. The Boer War. Abacus, 1992. p. xv ↑

- Hancock. p. 133 ↑

- Reitz, Commando, p. 156. ↑

- Fagan collection ↑

- Pieter Smuts’s letter to Die Burger 16 June 1986. Courtesy Fagan collection. The family graves were later exhumed, apparently in the 1960s, and re-interred in the Riebeek West cemetery. ↑

- National Monuments Council Proclamation No. 726, 18.4.1975 ↑

- Fransen, Hans; Mary Alexander Cook. A Guide to the Old Buildings of the Cape. Johannesburg & Cape Town. Jonathan Ball Publishers, 2004. p. 127. ↑

Fascinating article! Much I never knew. Thank you.

Chantal are you related to the Field Marshall?

Hello Hennie,

Sadly, not terribly directly. Family research has shown that my great grandfather was a second cousin, and his batman in the war. We’ve tried mightily to find more info without much luck. Our family is peppered with some familiar names though. My grandfather’s Christian name was Van Der Byl and my dad was Cornelius.

I must admit to a bit of nepotism here: Author Greig Stewart is my partner. But my admiration for his research and fascinating article stands. Thank YOU for keeping history alive with Nongqai.

Best, Chantal

Hello Hennie,

Sadly, not terribly directly. Family research has shown that my great grandfather was a second cousin, and his batman in the war. We’ve tried mightily to find more info without much luck. Our family is peppered with some familiar names though. My grandfather’s Christian name was Van Der Byl and my dad was Cornelius.

I must admit to a bit of nepotism here: Author Greig Stewart is my partner. But my admiration for his research and fascinating article stands. I know a lot about you. Thank you for keeping history alive with Nongqai.

Best, Chantal

Wonderful article, thank you! Mnr Heymans, ek skuld nog vir u ‘n stap om Smuts Huis in Irene. Ek is nou in Brisbane woonagtig, en is van plan, DV, om Oktobermaand weer in ons Moederland te wees, seker vir ‘n maand of so. Sal graag bymekaar wil kom. My epos is: pjweyers@gmail.com Beste groete, Philip Weyers

Good Day ,

@Greig Stewart

I notice you mention this award ..

“was awarded the Ebden scholarship to Cambridge,”

I wonder if you have looked up Mr John Bardwell Ebden, ?

A very interesting early Cape entrepreneur

There was also an Ebden PRIZE as well as the Scholarship

The topic for one of these competition essays had to do with Customs Unions

See .. /

“Selections from the Smuts Papers: 4 Volumes – Edited: W.K. Hancock and Jean van der Poel”

Volume 1

June 1886 – May 1902

“An essay entitled South African Customs

Union written in 1890 for the J. B. Ebden prize offered by the Univer-

sity of the Cape of Good Hope. The essay did not win the prize but was

highly commended. (See 14 b.) MS. of 58 foolscap pages in Smuts’s

handwriting, signed Philomesembrias”

Although Smuts did not win the essay prize the topic / subject would play a part in his later life after the ABW

Specifically regarding inter-state trade and the meetings and conventions held to work out these issues.

Which after 1908 culminated in the discussions relating to UNION and in 1909 the National Convention.

A huge story on it’s own.

BTW;

The University of the Cape of Good Hope established in 1873 became the University of South Africa – moved to Pretoria.

The history of the University of Stellenbosch will have to wait for another story

You could also look up Jean van der Poel – who later also has something to do with Customs Unions – and translates Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto into Afrikaans …

Further to my earlier post

https://mansellupham.wordpress.com/2023/08/04/george-holloway-1807-1879-petitions-7-october-1852-queen-victoria/

There is a huge amount of very interesting history contained in this page

How the stupid people of the Cape stopped a useful and large addition to the white population of the Cape Colony.