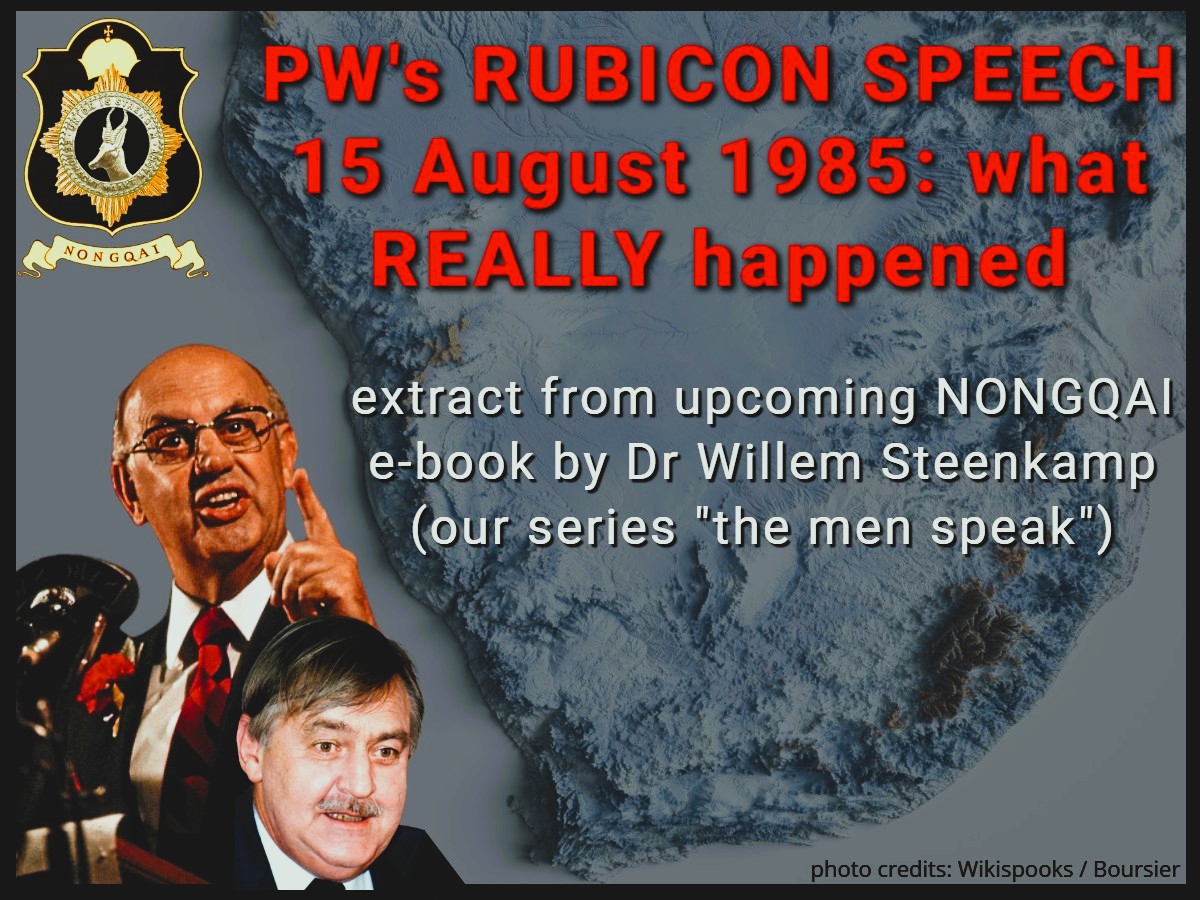

THE REAL HISTORY BEHIND PW BOTHA’S 15 AUGUST 1985 RUBICON SPEECH

Extract from an upcoming NONGQAI e-Book by our co-editor Dr Willem Steenkamp (a part of our campfire conversation series “the men speak”)

ABSTRACT: This article reveals the real history behind PW Botha’s 15 August 1985 Rubicon Speech. Because of the catastrophic consequences that flowed from it, it is important to understand the amount of dysfunction and discord in the South African government’s strategic decision-making at that time, as cause for the debacle.

KEYWORDS: President PW Botha; Foreign Minister Pik Botha; Rubicon Speech 15 August 1985

AUTHOR: Dr Willem Steenkamp (retired former ambassador, lawyer, intelligence analyst and political scientist).

READ TIME: 15 minutes

Forty years ago, on 15 August 1985, then South African State President PW Botha addressed the Natal provincial congress of the ruling National Party in Durban. The speech came at a tumultuous time. The internal security situation had deteriorated to the point that a state of emergency was declared on 20 July. On 31 July Chase Manhattan Bank decided to not roll over South African debt any longer, which decision was soon followed by other leading banks. The top-down, managed political change that Botha had imposed, such as the new tricameral constitution, had inflamed rather than lowered political tensions.

It was clear that those were serious times, requiring serious, well-conceived and expertly executed measures from government if it hoped to de-fuse the situation. What the country got instead, was the unmitigated disaster that became known as the “Rubicon Speech”.

What follows, is the real history of the astounding discord, deceit, and dysfunction within the government (with the two Bothas – PW and Pik – as the main protagonists) that caused this debacle.

Already during July 1985 the then minister of Constitutional Development and Planning (who was also the Cape provincial leader of the NP), Dr Chris Heunis, had conveyed to PW Botha that there was an urgent need to convene a top-level meeting of the extended cabinet to try and obtain consensus about new policy initiatives that Heunis and his department had been pushing for, but about which no agreement had been reached in the SCC, the Special Cabinet Committee on Constitutional Development which Heunis chaired.

This committee had reached a stalemate in its internal deliberations, with the senior ministers serving on it unable to agree on a new direction and Heunis thus not being able to advance the recommendations for reform that he had received from the constitutional experts in his department. Given the ruling National Party’s internal rules regarding the making and approval of new policy, these new initiatives had to be put to the four provincial congresses of the NP for approval. With the annual congress season about to begin in August, it was thus necessary to have such an extended cabinet “bosberaad” (brainstorming session) beforehand. PW himself was set to deliver the opening address at the Natal provincial congress on 15 August 1985, which would present a platform from which to introduce and explain the new initiatives that were about to be submitted to the provincial congresses for their approval.

Apart from this need of Min Heunis that cabinet-level direction be provided about new policy, the general situation – both internal and external – that confronted the government had rapidly deteriorated during July 1985 (as alluded to earlier). On the one side, this grave intensification of pressure related to the economy and the financial situation. The SA Treasury and Foreign Affairs had been warning for some time that ominous signs about South Africa’s debt were emanating from leading international banks, particularly in the USA (without, however, these warnings eliciting a timely response from PW).

On the other end of the threat spectrum, the internal security situation was also rapidly deteriorating. To the point where, on 20 July 1985, President Botha had declared a state of emergency in affected parts of the country where the unrest stoked by his decision to impose the tri-cameral parliament had been gaining in intensity. This emergency was placed under the management of the SADF.

The fact that PW had deemed it necessary to impose an emergency, brought his government’s grip on the country into question in the eyes of foreign investors, thus raising serious doubts about the stability and future viability of the country. This, plus shareholder and public pressure, caused Chase Manhattan Bank to decide on 31 July 1985 to no longer roll over its previously granted credit facilities to South African commercial banks (which decision had a snowball effect among other international banks, who rapidly followed suit). So that the SA government was consequently forced to unilaterally declare a debt standstill (in other words, a refusal to honour its debt obligations, on the grounds of temporary inability).

Against this backdrop, PW finally agreed to convene the cabinet, plus the deputy ministers and key advisers at the Military Intelligence training facility at the old Radcliffe Observatory (Sterrewag in Afrikaans) in Pretoria on 2 August 1985 for the top-level summit that Heunis had requested. The objective was to reach agreement in principle on proposals for new policy initiatives regarding constitutional development, particularly regarding the rights of black Africans (which initiatives he, PW, would then include in his speech set for 15 August 1985, when opening the Natal NP Congress in Durban). It is important to note again that NP party policy could not be changed by the cabinet – the ministers could only make recommendations to the provincial congresses, for their final approval.

It is common knowledge that PW’s notorious “Rubicon” speech was a disaster of the highest order in terms of public and international relations. In fact, it is recognised now as having been a turning point in terms of how the West would henceforth approach the issue of white rule in South Africa.

With all of that being commonly known today, you as reader may well ask: what need then is there for me to still dwell on this topic? The answer lies in its value as a learning experience about how decision-making within the PW Botha government occurred – what does the truth about what had actually happened (around the drafting and prior promotion of PW’s speech), tell us about the seriously dysfunctional nature of strategic decision-making within the then government, and the consequences of that dysfunction?

In brief, much of what has become commonly accepted wisdom about how this critical own goal was scored does not accord at all with what we now know had actually happened. Today’s common assumption that a grumpy old president had, in a flash of fury, at the last moment abandoned an agreed marvel of a speech that had reflected fundamental changes pre-approved at the 2 August meeting, and instead delivered a finger-wagging, deviant hectoring to the 200 million international TV audience watching, is simply not correct. The true causes of the debacle went far deeper than personal idiosyncrasy, and in fact reflected devious in-fighting, opposing strategy viewpoints and conflicting personal agendas that had rendered decision-making and co-ordinated execution completely dysfunctional, with cataclysmic consequences.

Thanks to the recent discovery of the full transcript of the 2 August meeting, plus original correspondence and documentation about how the drafting of the eventual speech evolved, we now have empirical proof that in fact was another prime example of seriously dysfunctional, un-coordinated strategic decision-making. Key players (above all, the two Bothas) had quite distinct own agendas and mutually incompatible strategic visions – again, what I’ve described as one camp preparing to “shoot” versus the other wanting to prepare to “settle”. Worst of all, they were actively (and deviously, in the case of Pik) working at cross-purposes, with Pik trying to paint PW and the conservatives in cabinet into a corner, and PW digging his heels in, determined not to allow himself to be so railroaded – no matter the cost to the country, considering the sky-high expectations that Pik had by then already stoked, unilaterally.

It was these internal shenanigans, more than anything else, that actually had caused PW’s 15 August speech to boomerang to the extent that it undeniably did.

Pik’s “lone ranger” actions and their disastrous consequences (as you will see from my recounting of it below) remind one very much of the even more calamitous consequences that PW Botha had triggered with that most infamous of his own “lone ranger” decisions as defence minister ten years earlier (namely, to launch Operation Savannah in Angola) which itself had proved to have been a watershed moment. It had been fatal to the Vorster team’s efforts to prepare the table for early negotiated settlements in Southern Africa, sinking the détente policy of that era.

The learning opportunity in this – when read together with the subsequent repeat performance between the two Bothas regarding the 1986 Commonwealth Eminent Persons Group initiative of Margaret Thatcher – is that the “ligte mistaaikie” of the Rubicon speech was not an isolated event, but rather was demonstrable proof of a pervasive pattern of dysfunctional strategic decision-making and often devious pursuit of opposite strategic and personal objectives within cabinet and government writ large. Which reality, of course, completely belies the popular belief of a competent, smoothly functioning, well-coordinated monolithic government and national security decision-making apparatus in which all members marched in lockstep and thought exactly alike…

We will get to the EPG head-butting directly after this section on the Rubicon speech – but first, back now to the Sterrewag cabinet meeting and the sorry saga of PW’s “Rubicon” speech.

Prior to the 2 August meeting, PW Botha had prepared his notes for his customary tone-setting opening address, designed to channel the direction of the “bosberaad”. These notes were also intended to form the core of his upcoming speech on the 15th in Durban.

According to the recently discovered full transcript of the original tape recording of the meeting, and as described by Prof Fanie Cloete: “The main discussion during the meeting consisted of consecutive formalistic position statements in the form of political shopping wish lists, first by the president and thereafter by one minister after another. It took place in typical P.W. Botha cabinet “discussion” style, in strict order of seniority in the cabinet. Furthermore, there was no real debate of the different views expressed, and each speaker only had one opportunity to state his views”.

In his opening remarks, PW Botha had made it very clear that he did not favour a unitary state, nor a federation or a fourth chamber of parliament as possible models for accommodating black African political aspirations. He underscored that the homelands had to be retained and that black Africans living outside of the then-existing homelands should have their “own affairs” managed at local government level (i.e., not at central government level), managing these in such a manner that it linked them to their respective ethnic homelands.

As regards the international situation, PW Botha declared that the outside world was unfair, uninformed, and foolish: “The Lord alone knows how we are going to live in this world… We will have to make our army and our police as strong as possible, because if they (the world) want to suppress us, we will have to fight like a self-respecting nation.” This notion of preparing to fight heroically to the bitter end was elsewhere echoed by PW Botha to his NIS intelligence chief, Dr Niël Barnard, when he told the latter privately at round about that time, that he (PW) suspected that the only remaining option for white South Africa was “to go down hard-arsed” – om hardegat onder te gaan.

After his opening remarks to the 33 party luminaries gathered there at the Sterrewag PW Botha essentially withdrew from the conversation and mostly just listened grimly to what his ministers each had to say. Among them, there was no clear consensus about the way forward. Minister Heunis was the only one to dare push for anything approximating significant reform. Pik Botha was uncharacteristically quiet through-out. Given PW’s forbidding posture, and despite the obvious concern about the economic, financial and security situation, the meeting did not reach any kind of agreement regarding significant change, nor was any definitive mandate given regarding the announcing of anything of the sort – despite what Pik Botha was to subsequently claim to the media and to foreign leaders (in fact, it was stressed that circumspection was required regarding revelations to the media, out of respect for the reality that the provincial congresses still had to be consulted).

The truth (as revealed in the actual transcript) is that the meeting did not reach any agreement on the SCC proposals put forward by Heunis. There were clear differences of opinion between the conservative wing and the more verligtes. Not once during the entire meeting was any mention made at all of the release of Mr Nelson Mandela – something that Pik Botha would subsequently specifically indicate to foreign government representatives and the international media as having been approved in principle, subject to conditions, and supposedly to be announced by PW on the 15th.

Unlike his normal custom, PW Botha did not sum up the points he regarded as agreed at the end of the meeting either. Instead, he requested that the SCC go back and work up policy guidelines for discussion by the upcoming party congresses. What was agreed, was that publicity about the detail of the personal views that the ministers had aired during their single speaking turns at the “bosberaad” (there had been no real debate) should be avoided, because of the twofold wish expressed by PW Botha that such guidelines firstly also be discussed with “legitimate black leaders” and then submitted to the NP party structures, before any detail be made public.

Leaving the meeting, Minister Pik Botha is said to have put on a show of exuberance. He enthusiastically told the two senior DFA officials who he had shortly afterwards summoned to his office to draft the DFA’s proposed text for the 15 August speech (Dr Marc Burger and Deputy DG Carl von Hirschberg) that momentous change had been approved, which he had been given the green light to go and inform the outside world about at the highest level, including alerting the international media of the importance of President Botha’s upcoming Durban address.

Ambassador Burger’s recollections about that drafting process are revealing, regarding what Pik Botha had told them supposedly had transpired at the 2 August meeting. This is what Burger had been made to understand about what had allegedly transpired at the “bosberaad”:

“The President had evidently confronted his colleagues with harsh realities. Realities which must have been agony to face for several ministers who still suffered from the Apartheid illusion and had, to date, steadfastly shut their eyes to the obvious. Their attitude notwithstanding, their own feelings were subordinated to the dominance of the hand that had fed and reared them. The essence of those days of reckoning was that “Separate Development” had failed, that Black political aspirations could not be accommodated in the “Bantustans”, and that the only alternative was common citizenship – with all that implied – for all in South Africa. A new constitutional order was required. It could not be imposed – only negotiated between all parties who would commit to a non-violent solution to the problem of our Gordian knot…” (Clearly, Pik giving this impression of what had occurred at the meeting to this staff, amounted to none other than blatant, deliberately devious lying intended to serve the own manipulative agenda he had unilaterally decided to execute).

In his book Marc Burger continued as follows: “Pik Botha had instructed that our draft was to make it clear that the President was announcing that his government was breaking with Apartheid and that “…. there was no going back!’ …

“I was the one who explained the historical significance of Julius Caesar bringing the legions he commanded in Gaul over the small stream (the Rubicon) that marked the border of Italy into which no Pro-Consul might bring his troops. “Allea iacta est” – the die is cast!

“The Minister’s reaction to my explanation was vintage Pik Botha: “… Hell!, was it unconstitutional?

“Yes Minister.

“But did it work?

“Yes Minister.

“Well OK, leave it in.

“The original text (of the DFA draft) … says break with Apartheid……..negotiations…….no going back – the battle plan of Foreign Affairs”.

(Burger, Marc. Not the Whole Truth (pp. 104-105 Kindle Edition).

The actual Sterrewag transcript, on the other hand, shows that there were absolutely no grounds for Pik’s assertions as to what had supposedly happened there. Nevertheless, judging by the subsequent written accounts of Von Hirschberg and Burger (the latter quoted above) Pik Botha had clearly insisted to his staff that important policy adjustments were indeed agreed upon and that these were to be announced on 15 August. He also set in motion arrangements for a whirlwind international trip to brief key governments and to prepare (and enthuse) the world media for what was supposedly to come.

Apart from the Foreign Affairs draft, Minister Heunis’ Department of Constitutional Development and Planning also provided one to PW Botha. In addition, the finance ministry also contributed some paragraphs on the economy.

When Minister Heunis went to personally deliver his department’s draft to PW Botha at his official residence at Groote Schuur in Cape Town, he saw that PW was in one of his angry fits – Heunis was not even invited inside and had to hand over the document on the stoep. Soon thereafter, Minister Heunis received an angry phone call from PW who told him in no uncertain terms that he would not deliver his (Heunis’) “Prog speech”. The draft prepared under Pik Botha’s supervision by Foreign Affairs had gone even further than the Heunis draft, including also reference to Nelson Mandela’s supposed liberation…

A week before PW was to deliver his speech to the Natal NP congress, Pik Botha had flown to Europe. Top-level meetings with SA’s main partner nations had been hastily arranged. On the 8th and the 9th of August in Vienna he briefed (separately) high-level representatives of the UK and the USA, which included Ewan Ferguson for Mrs Thatcher, and for the USA, Robert MacFarlane (National Security Council) and Dr Chet Crocker (Assistant Secretary of State for Africa). That these high-ranking representatives had personally flown to Vienna to be briefed by Pik, illustrates how important the upcoming announcements must have been presented as going to be.

What the Americans claimed Pik had told them PW would be announcing was: “the political involvement of blacks at the highest level, citizenship for all South Africans and the concept of a single territory for the whole of South Africa.” To Ferguson, he is said to have stated that PW would announce black “co-responsibility for decisions on the highest level that affect the entire country, one citizenship, and one undivided South African territory.”

Crocker later (in his memoirs) had this to say about Pik’s Vienna presentation: “Pik Botha was at his Thespian best, walking out on limbs far beyond the zone of safety to persuade us that his president was on the verge of momentous announcements. We learned of plans for bold reform steps, new formulas on constitutional moves, and further thinking relative to the release of Mandela.”

In Vienna Botha also briefed the international media, before flying on to Frankfurt to inform representatives of German Chancellor Kohl. (It should be kept in mind that, at this stage, Pik Botha had had no confirmation at all from PW that the president would use the DFA draft or any part of it as basis for his 15 August speech – quite apart from the fact that the Sterrewag transcript clearly shows that precious little of what Pik was proffering as being about to be announced, had in reality come even close to being agreed there).

The international as well as local media had accepted as gospel Pik Botha’s assertions (such as that PW’s 15 August speech “was going to be the most important event in South Africa’s history since the arrival of Jan van Riebeeck”) and were in turn creating a sense of high anticipation with their prelude reporting. Time Magazine’s Peter Hawthorne, for example, duly wrote that the upcoming speech would be the “most important announcement since the Dutch settlers arrived in South Africa 300 years ago”.

Pik, meanwhile, had seen to it that PW was provided with a detailed 11-page report (also recently found, together with the transcript) outlining exactly who he had been briefing abroad. PW thus knew full well the extent of the anticipation that had been created by Pik – not only in media circles, but also at the very highest government level among our key partners.

So, what happened in the intervening days, leading up to the 15th? We know already that PW had bluntly informed Heunis that he would not be delivering his “Prog speech”. On the 12th of August PW then convened a meeting of the most senior ministers, in his office. According to FW de Klerk, PW started out by dismissively hurling down onto his desk the drafts he had received. He then loudly stated that he would be delivering his own speech – the draft of which he then proceeded to read out loud, word for word, over the course of 45 minutes to his ministers “seated in front of him like schoolboys” (as Heunis would later recount to his son). After hearing it, not one of those present dared to object to any part of what PW intended to deliver on the 15th.

Of Foreign Affairs’ winged words, PW had only included the phrase that we have “crossed the Rubicon”, using it as the conclusion of his speech. Thus, he ended his address with baffling irony that only heightened the sense of disappointment – if the preceding content (or rather, its lack of anything substantive) was indeed seen by PW as the extent to which he was willing to “cross the Rubicon”, then what did that signify about the future ahead?

According to the FW de Klerk Foundation’s reference to what then happened on the 15th of August in Durban: “In the speech, President Botha expressed his rejection of ‘well-intentioned’ proposals for the solution of South Africa’s problems (probably a reference to proposals emanating from his more verligte Cabinet colleagues.)”.

Looking at the actual transcript of the “Rubicon” speech as delivered by PW Botha in Durban, it is notable that he started off with the following statement:

“It is of course a well-known tactic in negotiations to limit the other person’s freedom of movement about possible decisions, thus forcing him in a direction where his options are increasingly restricted.

“It is called the force of rising expectations.

“Firstly, an expectation is raised that a particular announcement is to be made. Then an expectation is raised about what the content of the announcement should be. The tactic has two objectives.

Firstly, the target is set so high that, even if an announcement is made, it is almost impossible to fulfil the propagated expectations. Secondly, it is also an attempt to force the one party into negotiations to make the expected decision. If this is not done, public opinion is already conditioned to such an extent that the result is widespread dissatisfaction…

“This is what has been happening over recent weeks. I find it unacceptable to be confronted in this manner with an accomplished fact. That is not my way of doing and the sooner these gentlemen accept it, the better”. (In other words, exactly the message to his own colleagues that the De Klerk Foundation referred to).

PW then went on to hector the outside world in his finger-wagging style, even warning them “not to push us too far”. The speech contained nothing that the outside world would have been able to understand as heralding significant reform – on the contrary…

According to Prof Herman Gilliomee: “In retirement, PW Botha told a journalist that Pik Botha had deliberately inflated international expectations in order to embarrass him, saying that that was ‘his (Pik’s) style’.”

The speech was seen live on local and international TV by an audience of 200 million. Given the elevated expectations that Pik Botha had deliberately created, it was received with surprise and deep disappointment – also among the well-disposed such as Thatcher and Reagan. The most immediate impact was in the economic and financial sphere. On 16 August 1985 the Rand fell by 20% and by 27 August it had reached a then historic low, so that the Johannesburg Stock Exchange and all currency trading had to be closed for three days…

The New York Times’s report on the speech contained some dire observations. Under the sub-heading “Result could be War” it stated on 17 August: “His talk struck many as a distillation of white intransigence heralding war, not peace, and a sign, if one was needed, that South Africa’s leader would not talk to those whom blacks consider leaders of equal or greater stature, such as the imprisoned nationalist Nelson Mandela.”

Pik Botha was said to have been “devastated” by the consequences unleashed. According to journalist Theresa Papenfus in her book “Pik Botha and his Times” Pik had phoned Peter Hawthorne of Time Magazine (who had, at Pik’s instigation, foreshadowed the speech as going to be the most important event since Van Riebeeck’s arrival) to apologize. Pik reportedly said to him:

“What can I do, Peter? What can I do to get this old bastard to change?”.

Within days of the speech, the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act was tabled in the United States Congress and was passed. Ronald Reagan vetoed it, but to no avail – he was overridden. Stringent US sanctions thus became a reality.

Margaret Thatcher also had her leeway to try and protect against punitive measures severely constrained by the speech and its fall-out, leading eventually to Commonwealth sanctions.

So, what conclusions can one draw from the whole “Rubicon speech” fiasco? Firstly, it is clear that the commonly held public perception that PW Botha had had some kind of brain seizure and at the last moment had abandoned a pre-agreed speech and just winged it with his own abrasive version, is an absolute misconception. PW always was going to deliver his own speech, to be based upon his notes for his opening address to the Sterrewag meeting – never based on the drafts provided by Heunis or Pik. All of the cabinet knew this, well before the 15th. They even had heard PW’s speech read out to them in full already on the 12th. No one then had had the guts to oppose any of it, or to point out that it would not sit well at all with the expectations that Pik had been deliberately creating.

Secondly, it is equally clear that Pik’s version of the Sterrewag meeting and what supposedly was agreed there (as provided by him to his own staff, as well as to representatives of the main Western powers and to the international media) had borne very little resemblance to the truth.

Just as PW had in 1975 unilaterally abused premier Vorster’s prior authorization for the SADF to covertly render only training assistance to UNITA to go ahead and order (based solely on his own authority as Defence Minister) the launch of a full-blown conventional armoured assault towards Luanda (Operation Savannah), Pik here had unilaterally decided, as Foreign Minister, to “expand” PW’s authorization for him to travel overseas into a “mandate” to present there his own version of what he would have liked PW to announce in Durban. Did he do it because he genuinely (and probably correctly) believed that the time had come to thus paint PW into a corner and thereby force him (and the conservative ministers) to accept the necessity for fundamental change, for opting to negotiate – to settle rather than shoot? Or, did he do it to cause PW embarrassment so as to improve his own chances of succeeding PW as president? Or a combination of both motives?

Did he, an intelligent and highly experienced diplomat, not foresee the damage that would result for the country, should his ploy fail and PW refuse to play ball? Did he choose to nevertheless proceed? For what personal or political reasons?

I will deal in much more detail with Pik’s personality in a later section. Suffice it to say here that, assessed from an objective political science perspective, the Rubicon episode was just one more in a litany of own goals that resulted from a clearly dysfunctional system of strategic decision-making and from fundamental discord and deceit among those key decision-makers as regards the best road ahead. Thus, it is an excellent example of the sorry reality that the then security/intel-community (including the NP cabinet) was a dysfunctional, un-coordinated, ideologically divided entity marked by deep discord on fundamentals, personal agendas, and underhand methods – definitely not the unified monolith marching in lockstep that it was popularly believed to have been…

We will soon see, in the next chapter, how the Rubicon machinations between PW and Pik were essentially to repeat itself within a year, regarding the visit by the Commonwealth’s Eminent persons Group (EPG). Essentially with the same calamitous consequences, occurring for the same essential reasons – dysfunctionality, discord, and deviousness.

(We expect to post further extracts from Part Three of Dr Steenkamp’s contribution to our “The Men Speak” series to this Blog in coming weeks, and hope to shortly have a download link for the complete e-Book available, free).

Thank you, a valuable read.

Good Day ,

Very interesting article but certainly not – new .. to those that follow this history

There are links and references included in the article. However where can one find the original source documentation ?

The debate around a Unitary state vs some form of Federation for South Africa is an old story although still very relevant today

The statement below by PM PW Botha ..( referenced in the article ) /

“In his opening remarks, PW Botha had made it very clear that he did not favour a unitary state, nor a federation or a fourth chamber of parliament as possible models for accommodating black African political aspirations.”

Is very interesting

To what extent did it agree – or disagree with the material and proposals by Minister Heunis ?

Is there a copy of these ?

Is anyone ( academic) busy with research in this area looking towards a PhD dissertation ?

One also wonders about the discussions that took place after the exit of PM PW Botha. The ascendency of F.W de Klerk and the discussions about the freeing of Mandela and negotiations with the ANC / SACP

Was there another “Sterrewag”

Did F.W act “unilaterally” ?

I would suggest that the deeper reality behind these events could well be the “REAL Rubicon”

With much relevance for recent current events in South Africa ( a new Constitutional “make-over” )

Hi Chris – the original Sterrewag transcript is part of the PW Botha collection at Free State University. As to ongoing academic research, I don’t know. FW de Klerk restored the constitutional convention of collective cabinet decision-making. The decision by cabinet taken shortly after FW became NP leader that government should abandon Apartheid was unanimous. Contrary to many current conspiracy theories, the decision about the 2 February 1990 speech and its content was also arrived at collaboratively, not unilaterally by FW de Klerk on his own. The last issue that needed to be resolved prior to the announcement was the unbanning of the proscribed organisations such as the SACP/ANC. Consensus was reached on this at a “bosberaad” held at D’Nyala with key cabinet ministers and senior intelligence staff present. The broad thrust of what was to be announced (without detail), was then shared on a “need to know” basis with those needing to prepare the ground, such as Foreign Affairs / the SA embassies abroad (I know this first-hand, since at that time I served at the embassy in Paris as First Secretary of the Information section). 2 February 1990 indeed constituted the real crossing of the “Rubicon”. Please keep in mind that this article was but an extract from my upcoming e-book on that tumultuous era (mid-1970s – early 1990s era, which will provide additional detail and context (the extract was placed on the 15th because of the 40th anniversary of the Rubicon speech). Thanks for your comment, and please keep an eye open for further extracts we plan to post, such as about the military’s sinking of the EPG visit, as well as what really happened regarding the so-called Information Scandal.

Many thanks for the reply

When may we expect the release of your book -and – where should we look for it ?

I find it strange that the politicians who stood silent during the pre-Rubicon “dressing-down” by P W Botha were after the ascendency of FW de Klerk quite ready to agree to a “capitulation” – the later negotiations for Mandela’s release whilst at Pollsmoor ( reading from Johnny Steinberg ) Although these early talks with Mandela did take place under PW Botha.

All very interesting but I am primarily interested in the constitutional proposals put forward by J C (Chris) Heunis – a Kaapenaar

I see his papers are also kept at OVS

Very interesting man – need to go and look him up

I would like to try and see if they have any commonality with those by Frederik Van Zyl Slabbert for the PFP ( Federal )

Federation / Secession very much topics on the “Radar”

1909 and 1910 much derided with very little understanding of the deeper history

As far as I know there has been no detailed and comprehensive study of this period and seminal event – UNION

Although they still remain as unresolved constitutional options / problems

Hi Chris – Prof Fanie Cloete (Stellenbosch) who in the late 80s was with Heunis at the then Constitutional Development may know if copies exist of that Dept’s inputs at the time. You should also look at this in-depth article on the “Skrik vir Niks” document that Fanie Cloet wrote for Nongqai: https://tinyurl.com/455fhtmu