CONSTABLE B CELE: SOUTH AFRICAN WW2 VETERAN (UNION DEFENCE FORCE)

Moonlight and Memory: A Patrol in the Summer of ’65

Brig Hennie Heymans

It was the summer of 1965. We reported for the night shift—21:45 to 06:00 the next morning. Sergeant W. “Tandjies” van der Merwe, already nearing retirement, inspected and posted us with his usual quiet authority. I was assigned as Section Sergeant—responsible for visiting the men on their beats—and driver of “Six-Seven, sixty-seven – King’s Rest.”

My van crew was Constable Bekinkosi Cele—a fine man, a true Zulu warrior. We trusted each other implicitly. He was a veteran of the Second World War and wore his medals and uniform with pride. The ribbons stood out beautifully against his drab tunic, a quiet testament to his dignity and service. His belt and boots gleamed with Tony Red Nugget polish, and his buttons shone from Brasso. He was always immaculate—disciplined, proud, and ready.

It was a warm summer evening. The moon rose over the Indian Ocean, casting silver light across the calm waters at Anstey’s Beach. We often joked that when it was cold and raining, the “best policeman” was on duty—because nothing much happened. But on moonlit nights like this, unpredictability hung in the air. A police captain in Atlanta, Georgia, once confirmed that full moons brought a surge of complaints there too.

While waiting for calls, we patrolled Marine Drive. The scene was almost romantic—hot, quiet, and bathed in moonlight. Nature offered its beauty freely, and I remember thinking how fortunate I was: the police were paying me to witness it. Still, it was sweltering, and we wore full uniform—no summer gear in those days.

Then came a call: a “Code 20” at the Barbeque near the wharf at Island View and Fynnlands. Young policemen love action. A “Code 20” could mean anything—from a frog croaking in a neighbour’s pond to a full-blown drunken brawl. We raced to the scene.

Upon arrival, Constable Cele said firmly, “There’s a big fight. I’m going with you. I’ll cover your back with my knopkierie. No one will attack you from behind—you take them head-on!”

We entered the lounge, which was at ground level. A handful of men were in a full-on brawl. The noise was deafening. For a moment, silence fell—then the chaos resumed. We approached the fighters to intervene. One man lunged at me, and I responded with a lucky shot to his chin—he went flying. A second man came to avenge him, and he too met the same fate. The fight stopped. We arrested both men—sailors—and charged them with “disturbance on a liquor-licensed premises.” Once they were safely in the cells, we resumed our patrol.

Minutes later, a report came in: housebreaking near the station. There we found “sailor number one”—he had escaped! He’d asked Sgt van der Merwe for permission to wash at the tap outside the cell and simply bolted. I brought him back.

Later, one of the ship’s agents arrived, paid their fines, and thanked us for a “fair fight.” The sailors returned to their ship, bound for the UK. Many of them, it seems, considered a brawl part of the drinking ritual.

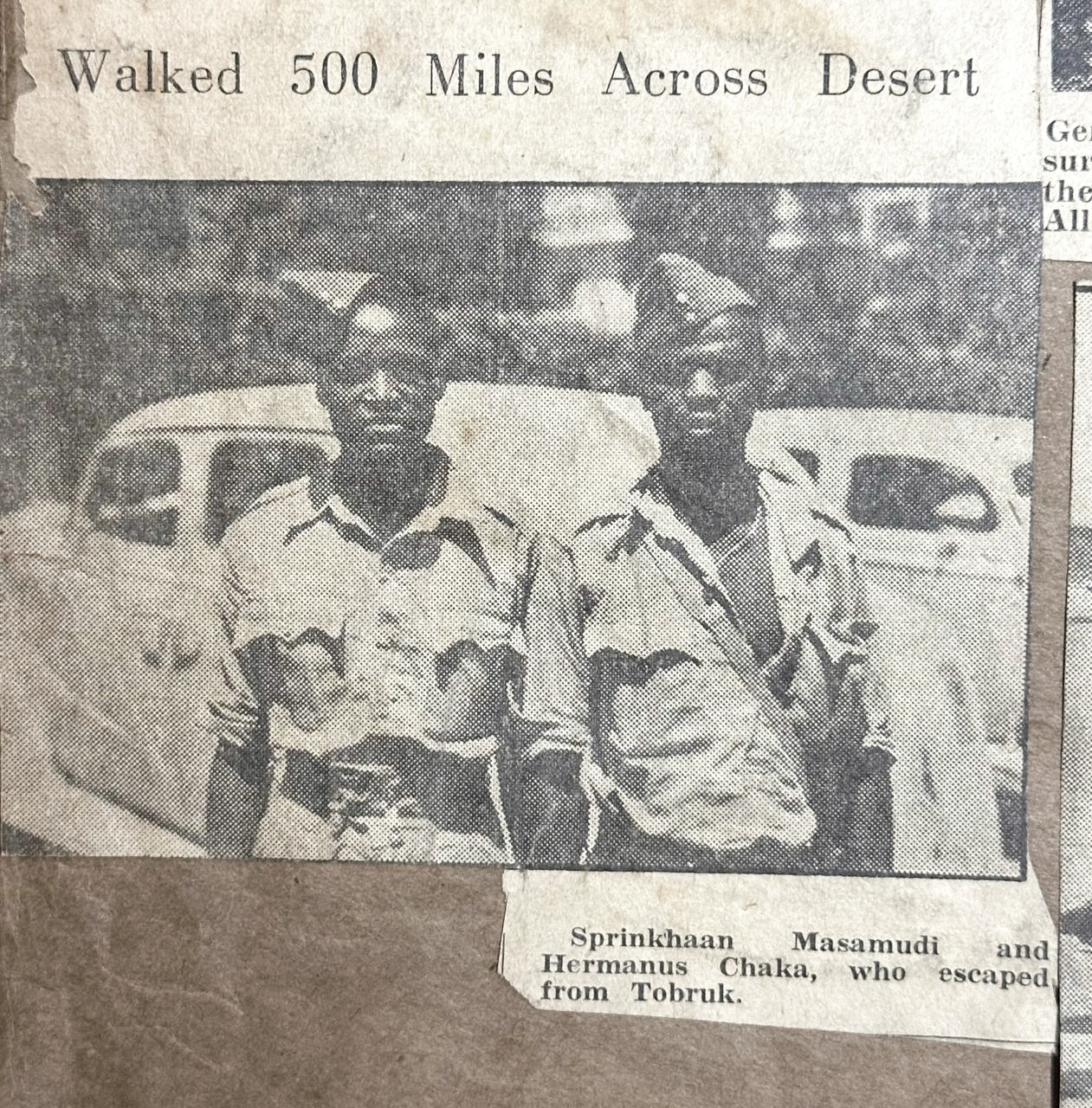

I share this story to honour Constable Cele’s loyalty. He trusted me, and we had a strong bond. He once told me he had served as a stretcher bearer “up north,” and that during the fall of Tobruk, the Germans never captured him—he escaped through the hlatini (bush, in isiZulu), hid, and later rejoined the British Army.

I was young and foolish—I never took a proper statement about his wartime experiences. Come to think of it, I never recorded the stories of my grandfather and grandmother either—both of whom were interned in British concentration camps during the Anglo-Boer War. In those days, we were all “poor”—there was no money for cameras or photographs.

Constable Cele showed me how to lie flat under attack—whether from hand grenades, aerial bombs, or other explosions. There are no secrets in the police. He shared many with me.

Today, I’m nearly 80. He must be long gone. But he was a good policeman, a brave warrior, and a man of strong character. A man I’ll never forget—especially after seeing photos on Facebook of what they endured “up north.” I include here a few images of other stretcher bearers, in quiet tribute to their courage.

South African Native Military Corps personnel captured at Tobruk, Libya on 20-21 June 1942. (Graham du Toit) Constable Cele was not amongst them.

Credit: Facebook: South Africans in WW1, WW2 and Korean War