1920 – 1948: The Palestine Police Force

Summary: The Palestine Police Force – A Legacy of Service and Lessons for South African Policemen

This article traces the history of the British Palestine Police Force (1920–1948), highlighting its evolution from a colonial gendarmerie to a paramilitary counterinsurgency force. Through personal anecdotes, historical records, and operational insights, it explores the challenges faced by officers amid civil unrest, political upheaval, and wartime pressures. The force’s pioneering use of tracker dogs (including South African Dobermanns), close-quarter combat techniques, and mobile strike units laid the groundwork for similar policing models across the British Empire.

For South African Policemen—especially those with township or border duty experience—the parallels are striking. From ambush tactics and community tensions to the emotional toll of service and institutional reform, the Palestine Police story offers valuable reflection on the enduring complexities of law enforcement in divided societies.

Why It’s Important to South African Policemen

• Shared tactical lineage: Palestine Police and mobile forces were influenced by SAP tracker dog units and methods of investigation.

• Historical continuity: Many former Palestine Police members served in Rhodesia and South Africa, shaping local policing doctrine.

• Emotional resonance: The moral dilemmas, camaraderie, and sacrifices echo familiar experiences in SAP history.

• Editorial stewardship: Preserving this history fosters understanding, healing, and professional pride.

Keywords

Palestine Police Force, South African Police history, South African Police Dog Masters, colonial policing, counterinsurgency, SAP tracker dogs, paramilitary policing, Tegart forts, Fairbairn-Sykes, PMF, Malayan Emergency, Rhodesian policing, historical policing parallels

SEO Sentence

Explore the history of the Palestine Police Force and its lasting impact on South African policing tactics, tracker dog units, and counterinsurgency strategy.

Introduction by Brig HB Heymans

This article offers a rare glimpse into the British Palestine Police Force (1920–1948), a colonial institution shaped by conflict, duty, and reform. With a South African Police lens, it draws meaningful parallels between past and present policing challenges. We extend sincere thanks to Marthinus de Lange for his thoughtful research and engaging writing—bringing international police history to life with clarity, relevance, and respect. We also see how Orde Wingate, a committed Zionist and later a general in Burma, operated in Palestine—where his distant relative, Col. T.E. Lawrence, once taught Arab forces to fight. Their stories reflect the complex web of loyalties and legacies that shaped the region. Understanding this history helps us reflect on our own.

THE PALESTINE POLICE FORCE

A Job Well Done

Marthinus de Lange

“Now there’s Hussein el Mohammed and Moses Moshewix;

Plus Parliamentary members safe in Tooting;

What’s mucking up the country with their rotten politics,

And leaving British coppers to the shooting . . ..”– Part of an old Palestine Police ditty

When one reads the above, it’s easy to imagine a typical police canteen or barracks setting with men singing songs, fuelled by the traditional policemen’s coping mechanisms of alcohol and nicotine. But, for me there was a bit more. I have only known two former Palestine Police members in my life (or at least those two men were the only ones to mention it) and whilst I knew of the force it was just something I wanted to read more about when I eventually got some spare time. After Brigadier Heymans’s article, about the SAP Dog Masters who served in Palestine, I began reading through a few books I had on the subject. Initially to find some more information on aspects of the Dog Master article. This led to some further correspondence with Brigadier Heymans, and he suggested I write this article. To do so I did further research and noticed that the more I read, the more of a kinship I was beginning to feel with these long-gone men, whose service time had coincided with that of my father and maternal grandfather. Despite the time difference, as a former South African Police township policeman, the similarities of their job and its challenges when compared to my former job were easy for me to see and I can easily understand the underlying frustration in the above-mentioned song. It really does seem to be the case of the more things changing, the more they stay the same.

On the 1st of July 1920 The Palestine Police Force was established. The legal authority of the Palestine Police Force (PPF) was granted, after the fact, by the Police Ordinance of 1921, although it is noted in numerous sources that despite this, no legal challenges were ever mounted against the PPF.

After the Palestine Mandate the British had inherited multiple police systems. The British wanted one police force with 3 districts and elected to maintain a gendarmerie system. This early police force was heavily based on the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) in both organisation and training. Initially it was a Palestinian Gendarmerie which was created in 1921 and made up of Arab, Druze and Jewish members. And, from 1922 a British Gendarmerie. The British Gendarmerie was the brainchild of Sir Winston Churchill who wanted a police force like the South African Constabulary or the Canadian Royal Mounted Police. Despite the name, Churchill does not appear to have envisaged much of a civilian policing role for the British Gendarmerie, and one has to wonder if the idea was not heavily influenced by his experience in South Africa.

The Royal Irish Constabulary was dissolved in August 1922, and the British Gendarmerie was recruited from former members of the Royal Irish Constabulary. Many of these recruits were former so-called “Auxiliaries” and “Black And Tans”. Constables, often unemployed Englishmen, Scotsmen or Welshmen who had fought in the First World War, recruited into the RIC for assistance during the Irish War of Independence. The “Black And Tans” and “Auxilliaries” were noted for their effectiveness (And sometimes their brutality) during the Irish Civil War where they had provided an effective counterinsurgency (COIN) component.

There seems to be some contention here. I have seen literature claiming that Black And Tans were officially recruited whilst the British Palestine Police Association website says they were not officially recruited but some managed to join anyway.

Even though they were offered 50% less pay than what they received as RIC members, many former RIC still elected to go to Palestine. In April 1922, 650 of these new recruits arrived for service at Haifa. One of them, the not yet 21-year-old, Douglas V. Duff. A WW1 Royal Navy veteran who was the youngest man in this new Gendarmerie. Despite his youth he had already survived the sinking of two ships as a midshipman in WW1 and had served in the RIC during the Irish Civil War. His book “Bailing with a Teaspoon” paints a very interesting picture of some of his fellow Gendarmerie recruits. He mentions that 95 percent of them had held commissions in WW1 and were, often, highly decorated soldiers and that most had served in the RIC in some fashion. They appear to have spanned all age groups from his not yet 21, as he puts it, to a former brigadier general, who had served in Flanders, and appeared to be serving under a section-corporal who had once been his brigade-major in Flanders! Apparently, previous rank did not matter much in the new force. Aside from the former British soldiers Duff also mentions a few foreigners who could best be described as ne’er-do-wells. He goes on to call all the new recruits a “Legion of the Lost” and says: ”In composition and spirit the Gendarmerie was very little different from those bodies of armed men who sailed for Palestine during the thirteenth century, after the first unselfish Crusading fervour had chilled, for, like them we were seeking new opportunities or oblivion; we were either tired of our own countries or they were heartily sick of us.”

Duff, despite his youth, was a very colourful character and eventually became a prominent figure in the harbour police. Serving in Palestine till 1932. His book and his exploits make for a very interesting and entertaining read.

Although these initial Gendarmerie men were recruited to form a mounted police force, there were insufficient horses and insufficient funds to procure more which resulted in many of the men serving as foot patrols. It is claimed that within a year of their arrival 60% of the new recruits had resigned. Poor pay and bad living conditions being the cause.

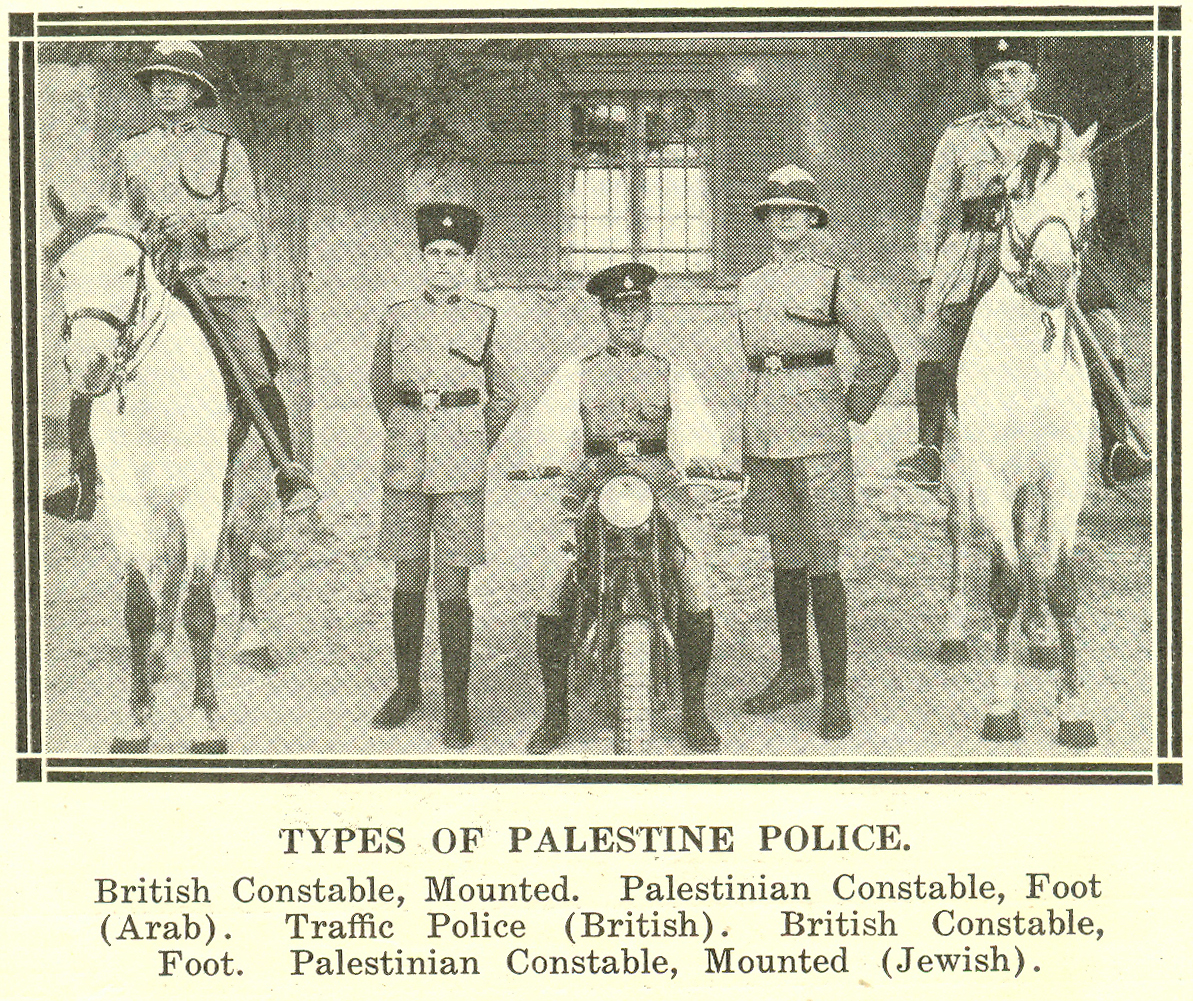

In 1926 the two Gendarmeries were disbanded and their members transferred to the newly formed Palestine Police which also had a separate British and Palestinian section. These two police sections worked separately in the same manner that the former two Gendarmeries had.

A large number of the Palestinian Gendarmerie members were also posted to the newly formed Transjordan Frontier Force, a paramilitary Imperial Service Regiment which took over the former British Gendarmerie’s border protection duties along with much of the older Arab Legion’s armoury. The Arab Legion, although initially intended as a police force, would, after service in World War 2 and the 1948 Arab Israeli War, later become the army of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. It had British officers (The famous Sir John Bagot Glubb being its commander from 1939) until 1956.

It would appear that this disbandment and restructuring was the first attempt at a regular civilian police force or at least an attempt at de-militarisation. The British Gendarmerie, as described by Duff, was clearly more of a mercenary style paramilitary unit than a police force. Duff himself describes them as mercenaries. The modern author Hughes, in one of his papers on the Palestine Police, refers to them as “Britain’s Foreign Legion”. So, despite the best attempts it seems they have gone down in history as such.

The newly formed British Palestine Police section was planned as a mobile force primarily to assist in riot control. Their training also reflected this. Most of them were in barracks at Mount Scopus with smaller detachments based at Haifa, Nablus and Sarafand.

It seems that the newly formed force spent a fair bit of time engaged in rescue and assistance work due to a string of natural disasters that plagued the area until around 1928.

Until 1929 the Arab majority and Jewish minority had lived in what is often described as “relative harmony”. In 1929 violence erupted between them. Both sides have their own account of why and that is not the focus of this article. The violence however caught the British at a very bad time with many of the police being on home leave. Sources state that there were only 90 British police left in Palestine at the time. On the 14th of August 1929 things came to a head when both Zionists and Muslims protested at the Western Wall. Because of the shortage of British members, the Trans Jordanian Frontier force was put on alert, and it was decided to rely on the Palestinian Police section even though most of its members were Arabs.

On Friday the 23rd of August thousands of armed Arabs assembled in Jerusalem for morning prayers and Jews fearing the worst began to flee the city. Kingsley-Heath, the commander of the police school, who had been placed in charge of the New City, ordered his men to confiscate the weapons. At 12:30 a large group of Arabs exited the Old City and an armoured unit from Ramaleh was ordered to Jerusalem. Kingsley-Heath and his men, to their credit, seem to have contained this matter and Jewish areas remained unaffected, except for the Montefiore Quarter, where Jewish residents were attacked.

In desperation the British began swearing in as many British males (Including a group of theology students on a field trip) as were available, as Special Constables and ordered troops to be sent from Cairo.

Unfortunately, none of this helped the people of Hebron. Approximately 67 people (sources vary) died there when Arabs, including one Arab policeman who was one leave, attacked the Jewish quarter. If one looks at the literature both Jews and Arabs seem to point fingers at the police for what happened during this massacre. However, it should be noted that there was only one British policeman in Hebron. Assistant Superintendent Raymond Cafferata who had only 11 Arab policeman (many of them elderly) and one Jewish constable under his command. His request to Jerusalem for British reinforcements (Arab policemen were considered unreliable to act against other Arabs demonstrating against Jewish immigration) was initially denied.

Cafferata ordered his men to fire on the attackers, shooting two of them himself. This included the aforementioned off duty policeman, who was in the process of committing a murder when Cafferata encountered him.

Despite the criticism levelled against his actions by many, Cafferata is credited as having helped save over 600 people. For his actions he was later awarded the King’s Police Medal for Gallantry.

Elsewhere in the country there were further riots, but they were contained with the assistance of sailors and marines from two Royal Navy ships anchored in Haifa Bay. When the riots ended 138 Jews had been killed by Arabs and 110 Arabs had been killed, primarily by British police. Sources note that 120 British police essentially prevented the country from falling into complete chaos and because of this Alan Saunders, the Acting Commandant, was awarded the King’s Police Medal for Meritorious Service.

The 1929 riots were a watershed moment for the police in Palestine and because of their failure to foresee the riots Sir Herbert Layar Dowbiggin, Inspector General of the British Ceylon Police, was sent to Palestine to advise on re-organisation of the force.

The Dowbiggin Report was published in May of 1930. The report was published secretly and to this day it remains unavailable to view online. Viewing is, apparently, available via the National Archives in the UK.

Amongst other things the report included recommendations for police protection of Jewish settlements. The retraining of the British Section of the Palestine Police as a civilian police force (Based on his experience in Ceylon, Dowbiggin wanted many police stations in rural areas) as well as their redeployment to stations to work beside Palestinian policemen. The CID would also, aside from regular investigation of crime, become responsible for intelligence gathering related to Palestinian political activities. For those interested in the Palestine Police CID and its intelligence gathering I highly recommend the book (see bibliography) “Palestine Investigated” by Eldad Harouvi.

On the 16th of July 1931 R.G.B Spicer commenced his tenure as Inspector General of Police and began implementing the Dowbiggin report’s recommendations.

Roy Spicer had served in the Ceylon police, was wounded in France during WW1 and later appointed to command the Kenya police where he met Dowbiggin. Dowbiggin (Who’s report had also included a recommendation for a change in leadership) recommended him for command in Palestine.

Spicer increased the size of the British section from 356 to 630 members. British members were now required to learn Arabic and work alongside Palestinian policemen at station level. A quote from the British Palestine Police Association website goes as follows: “The comradeship with their Arab colleagues often affected the attitudes of the British police who had little experience of working with the Jews. This was particularly the case post war.” If one watches the interview (Listed in the bibliography) with Mr Gerald Green, a former member of the Palestine Police, he also makes statements in this regard.

Spicer was a disciplinarian and perfectionist which did not endear him to many of the older members. He also went into great detail with regards to specifications for new equipment for the police, personally detailing things such as the length of the riot batons and types of horse shoes so as to enable horses to be used for riot control on cobbled streets.

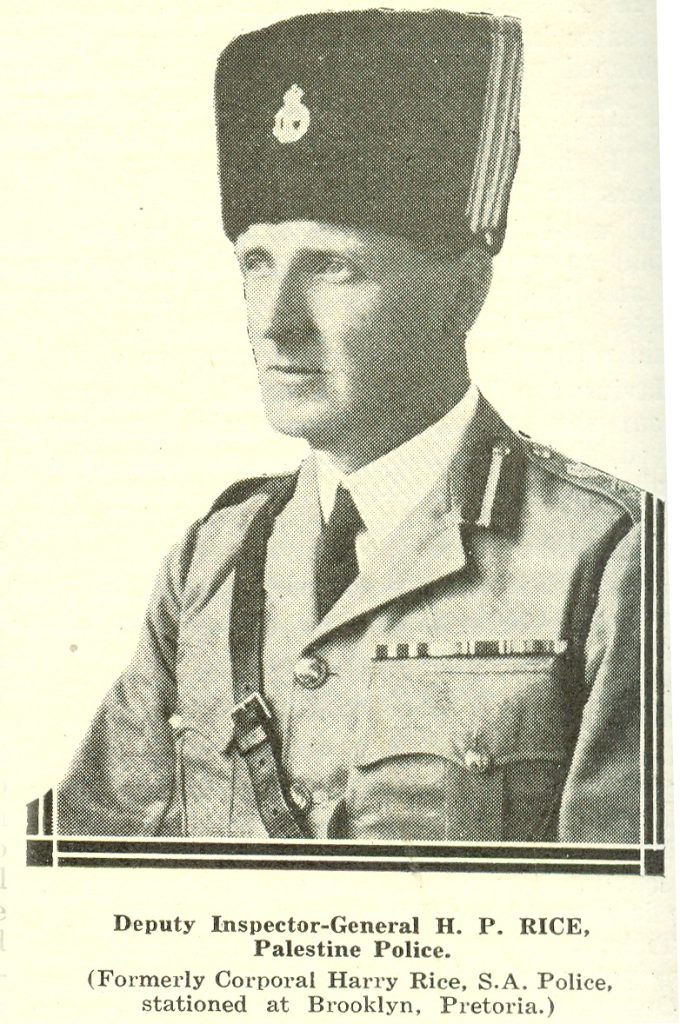

In 1932, as part of the changes in the CID, Spicer established a forensic laboratory at the Palestine Police Headquarters on Mt. Scopus. This laboratory predated its English counterpart by three years. It was also in 1932 that Harold Rice was chosen by Spicer as the CID commander. Rice, although born in Britain in 1886, had served in the South African Police from 1906 until 1915 and in the British army during the First World War. After that he returned to policing and served in Kenya, under Spicer’s command, as the commander of the investigative department. Spicer and Rice, by all accounts, seem to have gotten on very well. Haravouri goes as far as calling them “Soul Mates”.

Rice made several changes to the CID, establishing close co-operation with other neighbouring forces and military intelligence. In June 1933 a prominent Zionist politician was murdered. The CID initially brought Bedouin trackers to the crime scene, but they were unable to track the perpetrators successfully. The result of this unsolved murder was the establishment of a dog unit to be used along with the Bedouin trackers. Spicer sent Sergeant Parker and Constable Pringle to Pretoria, South Africa for a six-month training course with the South African Police Dog Training Depot. The men returned to Palestine in 1934 with three Dobermann dogs. At the time the South African Police were pioneering the use of tracker dogs and a South African Police Dobermann, named Sauer, had established a world record in 1925 when it and its handler, Detective Sergeant Herbert Kruger, tracked a stock thief, by scent alone, 160 kilometers through the Great Karoo.

Brigadier Heymans and I have theorised that, given the friendship between Rice and Spicer and the fact that Rice had served in the SAP, the tracker dogs may have been Rice’s idea. With the SAP Dog Training Depot having been established in 1911, Rice would certainly have been familiar with the dog’s success in tracking.

The newly acquired Palestine police dogs were considered very efficient by the CID and were used 95 times in their first year. After this more dogs were acquired from South Africa.

Some of the dog’s successes (It should also be noted that the use of the tracker dogs was not without controversy particularly with regards to the burden of proof when they were used) are detailed in the Palestine Police’s yearly summary in the bibliography. Brigadier Heymans’s blog post on the South African Dog Masters in Palestine, details some of the South African involvement. Of interest is the fact that Matthew Hughes’s article on Britain’s Pacification of Palestine makes mention of the Dog Masters speaking to the dogs in Afrikaans and that the Dog Masters wearing, what he calls, the South African-style slouch hat. This is certainly visible in period photographs.

In 1935 Rice, with the assistance of Royal Airforce intelligence, began to concentrate CID intelligence gathering efforts on two specific issues. Italy’s preparations for what at the time was considered an inevitable war (The Italians were attempting to infiltrate agents and distribute propaganda in the region) and the attempts of Arab parties to organise anti-government and anti-Jewish activities. At the time intelligence sources thought that the Arabs were hoping that a military conflict in Europe would lead to a change in policy in Palestine.

On the 16th of October a large arms shipment was discovered at the port of Jaffa. The shipment, which included light machine guns, rifles and ammunition, was destined for the Hagenah and caused the Arabs to believe that an attempted Jewish military takeover was imminent. In November Sheikh Izz al-Din al-Qassam, a prominent Muslim preacher and Arab leader, whose followers had previously been involved in raids on Jewish settlements and sabotage against the British infrastructure, launched his own attempt at a rebellion taking his men into the Gilboa mountains. On the 7th of November, after being surprised by policemen who had been tracing thieves, they killed an unarmed Jewish police sergeant.

Using the aforementioned tracker dogs, police followed the trail of the suspects to their hideout where one of al-Qasam’s men was shot dead. The area was then surrounded by police and on the 20th of November Rice launched his operation during which the sheikh and five of his followers were killed, others were taken prisoner and weapons, and equipment were recovered. Rice is said to have personally commanded this operation hovering over the area in a light aircraft.

The death of the sheikh and his funeral caused an uproar among many Arabs. During his funeral British policemen were violently attacked and stones were thrown at the Haifa police station. In the week following the sheikh’s death shots were fired at the police stations in Jaffa and a British policeman was shot at during an ambush. Rice himself noted that this was a first and expressed his concern that British government representatives would become targets of similar attacks.

Five months after the sheikh’s death, members of his movement shot and killed two Jewish farmers. This is considered to be the start of the 1936 to 1939 Arab revolt.

The Arab revolt remains a politically charged topic to this day and the politics of it are beyond the scope of this article. Once again both sides pointed fingers at the police after troubles escalated beyond initial strike actions. The British Palestine Police Association website details much of the actions against the police. These included ambushes. As a former South African township policeman, I was struck by the similarities in the tactics used against police in both countries. In Palestine the ambushes often involved shooting at policemen attempting to clear barriers that had been erected on roads as well as fake complaints to lure police vehicles into an ambush. I’m certain that many former SAP readers will also recognise these tactics.

On the 9th of September 1936, what is described as one of the worst disasters for the British Palestine Police occurred when four British constables investigating a report that a Jewish vehicle had been ambushed were themselves lured into an ambush in Galilee. The four of them faced 70 ambushers and despite being described as fighting to the last bullet they were all killed.

After the intercession of Arab royalty, the strike action was halted. Because of this intercession the British Government formed the so-called Peel Commission to investigate the problems in Palestine. For a while there was a brief period of normality in the region. However, there were still assassinations of Arab leaders and Arab policemen, including that of Salim Basta the deputy Superintendent in Haifa. After the publication of the Peel Commission’s report (Both Arabs and Jews were unwilling to accept the plan laid forth in it) in June – July 1937 violence increased once again. There was also an attempt made on the life of Spicer, and he was injured. Because of his ill health he left for Britain. In his absence Harry Rice was made Inspector General. Spicer would never return to Palestine. On the 26th of September the District Commissioner for Galilee, Lewis Andrews and his bodyguard were shot by Arabs after leaving a church service. This resulted in the British administration taking a harder line against Arab leadership with new laws, arrests and deportations.

In November 1937 Alan Saunders replaced Harry Rice as Inspector General. Rice then became Deputy Inspector General. Rice would stay with the force until 1938 when he retired after 38 years of service. He would later retire to South Africa where he passed away in 1973.

The Arab revolt continued and in some cases was effective enough to force the police to withdraw from smaller police posts. From 1937 a Zionist group, the so called Hagenah Bet commenced counter attacks on Arabs. Together with the Irgun (A Zionist paramilitary organisation established in 1931) many of whose members were military or paramilitary trained and whose bombs were more efficient than anything the Arabs had attempted, they made certain that the situation turned into something that could no longer be controlled by a civilian police force.

In 1937 two British Army Divisions took charge of the situation and by October 1938 the police were placed under operational control of the army. During this time there was some friction between the police and the army particularly with regards to the army’s attitude towards civilians. The British Palestine Police Association website has a quote from a senior policeman who was addressing an army officer.

“It is all very well for you bloodthirsty young fellows coming out here looking for a scrap. You come out for two or three years – and come on, confess it! – you rather look forward to being shot at in an ambush or something. But I am a Police Officer. I chose a profession in which I looked forward to maintaining law and order, to being the father of my people, to stop people being murdered, to keep the peace, to encourage people to come and tell me what is up, so I can look after them.”

Some sources state that the army was critical of the police for their thuggery, whilst some others say that the British police were shocked by the army brutality which in some cases resulted in massacres.

In December 1937 Sir Charles Tegart arrived in Palestine to assess the situation. It’s worth noting that Tegart, who had been Commissioner of the Calcutta Police, was regarded as “The Empire’s highest expert on policing unruly areas”. Tegart was a proponent of militarised policing. He advised Sauders to increase the size of the CID and re-organise the CID’s Political Section. He also advised that Sauders construct a frontier fence along the Northern border and a series of concrete reinforced police stations and pill boxes. These would in effect become Tegart’s legacy. Saunders accepted Tegart’s suggestions. The fence (The barbed wire had, ironically, been bought from Mussolini’s Italy by a Jewish building firm since there was insufficient barbed wire in Britain) was sabotaged before its completion and was always contentious since it crossed private land and pastures. As a result, Arabs often simply took it down. At the end of the Arab revolt, it was removed. Several of the reinforced buildings known as Tegart Forts, as the concrete reinforced stations became known, still exist in modern day Israel with some of them still being used as police stations or jails.

The Jewish settlements had retained their own guard units, which had been set up in 1936 because of the Arab revolt. These guards, the so-called “Notrim” (Hebrew for guards), were nominally under the control of the Palestine Police (They generally had a British commanding officer) but were effectively under Hagenah control. In 1937 the Notrim were expanded due to lack of British Manpower. In 1938 a regiment of Notrim was formed to guard the Palestine railways. The Palestine Police Railway Department. This Jewish police unit, despite its actions being controversial, was considered very successful by the British.

In June of 1938, once again as a result of a shortage of British manpower, Captain Orde Wingate of the British Army intelligence was given permission to create his Special Night Squads. The Special Night Squads were a counterinsurgency unit who ambushed Arab saboteurs and raided suspected bases and villages. Initially made up of British soldiers; they later included members of the Notrim. The Night Squads were criticized by the British, Arabs and Zionists for their brutality but, despite all of this, Wingate (who often accompanied his men on operations) was Awarded the Distinguished Service Order and the Special Night Squads were considered to have been effective in stopping the revolt.

In September of 1938 the Munich Pact had been signed, this allowed Britain to send more troops to Palestine. This enabled the revolt to be put down before the start of WW2. According to the British Palestine Police Association at least 28 British Palestine Police were killed during the revolt both on and off duty. Sadly, that was not the last of the assassinations and on the 26th of August 1939 two police inspectors were assassinated by means of a remote detonated landmine. Only instead of being Arabs this time the perpetrators were Jewish members of the so-called Stern Gang. This action met with wide condemnation from the Jewish community but would foreshadow much of what was to come in future years.

In the run up to World War Two the police inspected the preparations for war, enforcing blackout regulations and rounding up enemy nationals (Primarily German Templers who had a settlement in Palestine) and placing them in internment camps or prison. At the time Palestine was experiencing relative peace and many of the British Palestine Police members began to grow restless feeling that they were being wasted on administrative work whilst their country was at war. The men were employed on a contract basis and upon completion of their contract (Or upon buying themselves out) they would be free to go. Fearing the loss of many members the Inspector General of Police cancelled the service contract forcing the men to remain in the Palestine Police Force as conscripts. This proved to be immensely unpopular.

In June of 1940 things suddenly changed when Italy entered the war and France fell. Both Arabs and some Jewish organizations were negotiating with the Nazis and many vulnerable key points needed to be protected. As per usual there were simply not enough police for this. In 1941 the British tried to solve this with what can best be described as their own “Kitskonstabels” (a somewhat derogatory term for SAP special constables that will be very familiar to former SAP readers) Thousands of these watchmen and Temporary Assistant Constables were appointed. Because of time constraints training was rudimentary at best but their presence allowed for regular police members to be freed up for more important duties.

When Rommel’s Afrika Korps arrived in North Africa, Operation Final Fortress was put into action. Part of this plan was essentially the pre-war Tegart plan revived and fortresses like the Tegart forts were to be built throughout Palestine. These forts were filled with British Palestine Police members who had effectively become members of the armed forces in 1942. The police would later play a part in the Allied invasion of Syria and in the army Habforce, a relief column sent into Iraq to assist an encircled RAF base. In both cases the police provided trucks and drivers. The police had gained experience removing roadblocks under fire during the Arab revolt and this came in very useful with several members mentioned in dispatches and receiving decorations for doing so.

The police who garrisoned on the northern frontier made use of Arabic speaking Notrim members. One of these was no less than Moshe Dayan who had served in the Notrim and Special Night Squads. Dayan lost his eye during the Syrian campaign, when the binoculars he was using to scan Vichy French positions were struck by a sniper’s bullet.

Later the police would become heavily involved in military intelligence work, with one unit travelling to Beirut and the other involved in the so-called push to Damascus.

After Rommel’s defeat, the Palestine Police faced another problem: the resurgence of Jewish organisations (During WW2 the Zionist had agreed to a de facto peace with the British) who seemed intent on launching an armed struggle against the British. On the 12th of February 1944, they commenced a bombing campaign against government buildings. In March they went as far as attacking police stations and the Tegart Fort at Latrun.

Faced with the escalating attacks the Inspector General of the Palestine Police (Captain Ryner Jones) once again resorted to a paramilitary style of policing. Rymer’s creation was the Police Mobile Force (The British War Office allocated him 2 million Pounds and 800 servicemen who had been serving in Italy, North Africa and Britain). These men would form a militarized strike unit under Palestine Police command. The 8 PMF companies were equipped with military equipment including light artillery and trained as soldiers who wore military battle dress. The establishment of this unit (Often called Rymer’s Babes) caused some friction with regular police, particularly with regards to the young officers who had no experience in policing and were therefore looked down upon by regular police.

Eventually all members of the police would receive paramilitary training, and all of the new recruits would have to serve in the PMF before they could transfer to the regular police. This can be seen in the recruitment film in the bibliography. PMF units would also work closely with the Palestine Police tracker dogs when tracking Jewish saboteurs.

A reference once again refers to Dobermanns. However, it’s unknown if these were also obtained from South Africa or if they were bred in Palestine, since mention is made of the Palestine Police attempting to start its own breeding program. The recruitment film provides an interesting view of (albeit a possibly idolised version such as many recruitment films tend to present) the life of post war Palestine Police Force members and shows details of some of the training and day to day life. It, and the reprint of the Palestine Police Force Manual, show the paramilitary nature of some of the training as well as the unarmed combat and instinctive shooting methods.

On a more humorous note, the reprinted Palestine Police Force Manual has a section entitled “General Hints for Police Personnel”. It seems that colonial era police liked to use the term hints. I am sure many former SAP readers will remember “Hints on Investigation of Crime”.

For a firsthand account of life in the post war Palestine Police, Mr Gerald Green’s previously mentioned YouTube interview is very interesting. His career path followed one that would be familiar to many readers. A 17-year-old, who left school and joined the police, Mr Green was wounded twice during his service. Once during a Zionist bombing.

By October 1945 the Hagenah was estimated to be the largest Jewish insurgent force with a possible 5000 members. Between 1945 and June 1946 Jewish resistance killed 13 members of the Palestine Police and wounded at least another 63. Despite this it seems that it was the June 1946, Jewish attack on road and railway bridges, effectively cutting off Palestine, that forced the British into action. In response to this the British Authorities launched Operation Agatha to put down what they were by then terming the Jewish Revolt. Operation Agatha, although a military operation, required police co-operation to search and arrest civilians. The operation resulted in many arrests and the discovery of incriminating documents as well as many arms caches.

During Operation Agatha the police took these documents to the Secretariat offices in the King David Hotel. This was then targeted by the Jewish paramilitary organization to destroy the documents. On the 22 of July 1946 a bomb planted in the hotel basement exploded killing 91 people, 3 of them policemen, a further 49 people were injured.

In the aftermath of the bombing anti-Jewish sentiment increased amongst the British and tensions greatly increased.

In response the police launched Operation Shark. With the assistance of British paratroopers, the police cordoned off the whole of Tel-Aviv and parts of Jaffa. Policemen assisted by soldiers then conducted house to house searches. Men and women were taken to various places, primarily parks and schoolyards to be questioned by the CID. Years ago, I personally spoke to an Israeli lady who was a young woman in Tel-Aviv when all this happened. She called the police and soldiers brutes for doing this and likened them to the Nazis. Over the years I have heard this sentiment a few times when talking to Israelis who were there as young adults or children. Both sides of the story are presented on the British Palestine Police Association webpage dealing with Operation Shark. As tends to be the case with such things, what one person perceives as a brute is often simply a young man following his orders and trying not to run afoul of his superiors.

November 1946 is described as having been a tragic month for the Palestine Police. Irgun insurgents killed 4 British Palestine policemen by luring them into a trap with an anonymous phone call claiming that there was an arms cache in a house. While they were searching for the house a bomb exploded. In the following days another 6 policemen were killed in bomb attacks. In a personal conversation with a former British Palestine Police member, who was serving during this time, he mentioned to me that whilst Arabs would use knives or swords or shoot at you from a distance with a rifle (In contrast to what one hears now from the middle east he praised Arab marksmanship particularly that of the Bedouins) the Jewish insurgents had a liking for bombs which many of his fellow colleagues considered cowardly. In some conversations he would refer to the Jewish insurgents as gangsters, a view that seems to have been echoed by Mr Green in his interview. This is only mentioned since it serves to illustrate the police morale at the time and how such traumatic events will forever colour a person’s perception.

On January the 1st 1947 the trial of Dov Gruner began in a military court. Gruner was a Hungarian born Jewish member of the Irgun who, after he had left the British military, had participated in a raid (An attempt to obtain weapons) on a police station. During the ensuing firefight he was badly wounded in the face and had remained in captivity recovering from his injuries until his trial. An account of his trial, as written by police Inspector Denley, whose own family had been resident at the police station that was attacked, can be seen on the British Palestine Police Association website. Gruner’s American sister had gained worldwide sympathy for her brother since he had neither killed nor wounded anyone during the raid on the police station. Both President Truman and Winston Churchill pleaded on his behalf but all of it was to no avail, and he was sentenced to death. Gruner’s sentencing led to a new low in the already strained Anglo Jewish relations.

On the 11th of January 1947 members of the so-called Stern Gang dressed in British Palestine Police uniforms, hijacked an RAF truck and kidnapped its civilian driver. The next afternoon one of them, still dressed as a policeman, drove the truck into the police compound in Haifa. The driver challenged and shot at by guards, who had noticed a burning fuse, escaped. While the compound was being evacuated the bomb exploded killing 4 policemen and wounding many more. This is thought to be the world’s first car bomb, although it received very little press coverage at the time.

The bombing severely affected the morale of members of the police. One of them, Jack May, was to later become responsible for the bombing of The Jewish Agency Press Office on the 17th of March 1947. May’s bomb detonated when the building was empty, and no one was killed or injured. Sources claim that he was motivated by the murder of his best friend during the bombing of the Haifa compound.

Dov Gruner was scheduled for execution on the 30th of January 1947. However, the British feared for the safety of British civilians and delayed the execution pending an evacuation of civilians. This action further directly impacted police morale, since all of the married member’s families were to be evacuated. Some of the family members had been born in Palestine and knew no other home. The evacuation began in February 1947 and although some families were flown to England, over 1000 women and children were evacuated to Cairo where they were housed in an army camp. Some sources describe the conditions in the camp as being little better than imprisonment.

On the 16th of April 1947 Gruner and 3 other prisoners were executed. This was done secretly since the CID feared that the Irgun would attempt to free the prisoners. The Irgun would in fact later stage another jailbreak freeing prisoners in trucks. After the execution the prisoner’s families were taken to attend the burial, the area having been cordoned off by the army.

A so-called “stand-to” was declared for the police which was to remain in force until April the 22nd. A curfew was declared, and police were not allowed to leave their stations unless they were on official duty. Even then they were supposed to only leave in groups.

This was a very tense time in the region and from reading the accounts of policemen (Including one account from a young constable, who had only attested on New Years eve 1946) everyone was on edge.

On the 29th of July 1947 the Irgun murdered two kidnapped British Police sergeants. Their bodies were then boobytrapped and hung from tree branches. Police were informed of the bodies location and international journalists accompanied police headed to the location. These journalists then took pictures as the police cut down the bodies, which then exploded. Photographs of this act were published internationally and caused riots in several British cities.

Angered by this act several young and disgruntled PMF members bent on vengeance took six of their armoured cars into Tel-Aviv and launched their own attack, killing 5 people in the process. Police investigators were unable to get any information out of the young men and since the firearms had been cleaned and the ammunition replaced, nothing could be proven. No criminal charges were brought because of this incident which created further division. The Police Mobile Force was disbanded because of this.

Between 1942 and 1947 there were 162 policemen killed. Quotes from that time refer to the area as “the most lawless country in the world” and that “Arabs are not readily amenable to modern policing” and that “many Jews hate policemen”.

Georgina Sinclair (see bibliography) notes that as the situation was worsening the number of police auxiliary units increased. Sinclair is one of the few references I have found to the so-called “Snatch Squads”. In private conversations, with a former British Palestine Police member, I had previously heard of these squads and some of the specialised training they received.

The squads were set up by Brigadier Bernard Fergusson, an Assistant Inspector General who had served in Burma. Ferguson appointed two former pupils of his, Roy Farran and Alastair McGregor, who had both served in the SAS during the war, to lead the squads. According to Sinclair, aside from members of the Palestine Police, the squads were also made up of Airforce and army members. Although initially intended to train other police members in commando techniques these squads performed a counter insurgency function of their own with Sinclair’s article describing them as follows: ‘the main object being to flush out terrorist nests and then either arrest or shoot to kill’. Some sources mention Farran as being a “Free Hand Against Terror”.

Sinclair makes mention of the Snatch Squads using the Grant-Taylor methods of close quarter combat. These would be the same methods described in the manual in the bibliography. The Palestine Police Force Manual. Palestine Police Force Close Quarter Battle Revolvers, Automatics and Sub-Machine Guns.

Among collectors and enthusiasts this manual is referred to as the Grant-Taylor Manual.

Hector Grant-Taylor was a contemporary of William Fairbairn (He is thought to have trained with Fairbairn’s close friend and colleague Eric Anthony Sykes) and trained people in close quarter combat during World War Two. He was seconded to the Palestine Police force and would travel through much of the Middle East, training several units including SAS troops. The manual was put together from notes taken by one of his students. G.A. Broadhead, a superintendent in the Palestine Police Force. It was put into official usage from 1943. For those unfamiliar with the subject matter: Fairbairn and Sykes developed a close quarter combat method for the inter-war Shanghai Municipal Police, where Fairbairn also founded the world’s first SWAT team. This training was used by many police forces of the time and the Allied forces during World War Two. What appears in the film and manual is very much along the lines of the above. Although some of the unarmed combat in the film seems to have been modified for non-lethal usage. This is all made more interesting when one considers that the later Israeli methods of instinctive shooting and unarmed combat are heavily influenced by Fairbairn and his colleagues’ teachings. Possibly because so many Israelis were familiar with them from their service in the Palestine Police or British military. The Israeli method of pistol shooting, which is still in use to this day, owes its existence to the pistol techniques of men like Grant-Taylor and Fairbairn. Some former SAP members will remember learning the Israeli pistol methods (Sometimes referred to as the Cat stance) that were very different to the Weaver Stance that we were used to.

In personal conversations with the former British Palestine Police member, whom I trained in Jujitsu with, I was told that members of the squads learned some of the more lethal Jujitsu techniques. Their training also included knife techniques, assumedly for the Fairbairn Sykes commando knife. These techniques would have contrasted quite a bit with some of the general police self-defence shown in the police manual, as well as in the recruitment film.

These Snatch Squads appeared to have enjoyed, what Sinclair describes as, free reign. Their operations against Irgun and Stern Gang members appear to have been successful. However, after some of the details of the operations emerged and Farran was implicated in the murder of a young Jewish man who was putting up propaganda posters, the squads were disbanded and their operations ceased. Although Farran was found not guilty of murder, Brigadier Fergusson was forced to resign.

Facing increased violence and unable to find a solution for both Arabs and Jews, Britain eventually had no option but to withdraw from its Middle Eastern Mandate. In 1947 the British government formally placed the question before the UN. On 29 November 1947 the UN voted in favour of a resolution adopting the implementation of the Plan of Partition with Economic Union as Resolution 181 (II). This plan was eagerly accepted by Jews in Palestine but rejected by the Arab leadership and people. Britain accepted the partition plan but refused to enforce it arguing that it was not accepted by the Arabs. In September of 1947 the British Government announced that their Mandate for Palestine would end at midnight of the 14th of May 1948.

British members of the Palestine Police were shocked by the UN vote and worried about their future employment and pensions. Many policemen began the search for new employment, and many police forces began “head hunting” in the area hoping to recruit trained policemen for their own ranks.

Arab members of the Palestine Police had no such luxury. For them the future was uncertain. Many of them lived and worked outside of what was declared the Arab section. In the end many of them deserted, taking police weapons with them, to join the Arab Liberation armies, others remained in the vain hope that the British would look after them.

For Jewish members the future looked better, most of them already lived and worked in the area that had been allocated to the new Jewish State. Most of them would remain policemen or serve the new Israeli Government in other forms.

Following the UN vote, an effective civil war broke out between Arab and Jewish communities. Police, now seriously undermanned and without any help from the army, were essentially powerless. Riots, bombings and massacres were the order of the day. These are detailed, often with witness accounts on the British Palestine Police Association website

On the 16th of December 1947 the Palestine Police Force withdrew from Tel-Aviv relinquishing the responsibility to Jewish police. Other British government services began withdrawing from the country and in March 1948, all British judges were returned to Britain.

The army was put in charge of evacuating British civilians. Police stations were to be evacuated quietly with lower ranks not receiving any advanced information regarding the date of their evacuation.

Police members from smaller stations were, given sufficient experience, redeployed to District Police HQs. Others were kept in transit camps in Haifa, until British troop ships could take them back to Palestine. Young, inexperienced policemen were the first to be evacuated.

Mr Green’s video interview mentions how some equipment, including armoured cars, was destroyed prior to the evacuation.

Once again, the British Palestine Police Association website provides eyewitness accounts of the evacuation. Some of these accounts are very sad, since many members had Arab colleagues, they had become friendly with and felt they were betraying them. Members were also forced to leave personal property and pets behind. In a personal conversation with a member, who was there during the handover, I recall that I was struck by the fact that he was not so upset by some of his belongings that he had left behind but was, 40 something years later, still very upset about leaving his police horse behind. He had apparently grown very attached to the animal.

On May the 15th 1948, the few British police left in Jerusalem were the last to be evacuated to Haifa.

On the 30th of June the last British troops were evacuated from Haifa, the British flag was lowered and the port officially handed over to Israeli authorities. This marked the end of an era.

On the 20th of July 1948 the British Section of the Palestine Police paraded at Buckingham Palace. King George VI presented medals and made a speech which concluded with these words:

“I have admired the forbearance and courage with which you have met the difficulties and dangers of service in Palestine. Many of your comrades have given their lives and many others have been injured in that service: their sacrifice will not be forgotten.

Your task in the Palestine Police is now completed and you can look back on a job well done. You will soon be turning to employment elsewhere, and, wherever your future may lie, I wish you every success.”

The Palestine Police are the only colonial police force to march yearly to the Cenotaph in London. In October of 2002, approximately 100 surviving members would do so for the last time. According to Sinclaire’s article one former member remarked: “it was heartbreaking to see the young lads I had marched with at Mount Scopus limping along to attend the Memorial Service to the lads who still lie in the Holy Land.”

In 2021 British Palestine Police Association celebrated the Centenary of the Foundation of the British Palestine Police. The actual centenary would have been in 2020, but COVID-19 resulted in a postponement. A service commemorating the 349 men who lost their lives keeping the peace in Palestine was held at the Temple Church in London. A booklet entitled “Policing the Holy Land” was published as part of the centenary. The booklet’s editor is the British Palestine Police Association Treasurer and Legal Advisor. He is also the nephew of one of the inspectors assassinated by the Stern Gang in 1939.

Between 1926 to 1947 approximately 10000 men (Only one woman was ever attested, she served as a Police Matron) passed through the Palestine Police training depot. Former members of the Palestine Police would go on to serve in Malaya, Hong Kong, Aden, The Canal Zone, Libya, Eritrea, Cyprus, Kenya, Mauritius, Northern Rhodesia, Caribbean and the Pacific Islands.

Of interest is the fact, that the last serving member of the Palestine Police was R.G.W Lamb who served in the Falklands during the time of the Argentine invasion.

In the case of the man that I trained with he would, before moving to Southern Rhodesia and later retiring to South Africa, serve with the Northern Rhodesia Police Mobile Unit in the Copper Belt. This unit was apparently modelled on the Palestine Police PMF and had many former Palestine Police members. This anecdote was confirmed for me by Sinclair’s article mentioning the same unit.

In contrast, an Israeli gentleman of my acquaintance, having begun his career with the Palestine Police as a Jewish constable, would eventually retire as an officer in the Israeli Shin Bet.

The expertise in counterinsurgency warfare that had been gained by the Palestine Police was passed on to other colonial forces. By the mid-1950s, most colonies were experiencing various degrees of unrest or insurgency. In many of the colonies, internal defence fell upon the police which necessitated a paramilitary police force with mobile strike forces, much the same as had been the case in Palestine. The Palestine Police Force, particularly the PMF, served as the model for these. Former Palestine Police members would go on to serve and, in some cases, command such units in many of the colonies. The Malayan Emergency had started at roughly the same time as the Palestine Police were disbanded and over 400 Palestine Police members would go on to serve there with 70 of them being killed during counterinsurgency operations. Two years after the start of the Malayan Emergency, the police there were already being called a paramilitary organization as opposed to a police force.

In my opinion, one could say that the counterinsurgency experience of these Palestine Police members, particularly those who served during the Malayn Emergency and Kenya and Northern Rhodesia, would go on to shape Rhodesian counterinsurgency tactics (Many of which had their origins in methods used during the Malayan Emergency) where it was later passed on to South Africans and eventually to many of the former SAP members who are reading this.

In the end paramilitary style policing, in a dangerous and divided country, at the mercy of political forces far beyond one’s control, and disliked by large numbers of the population, remains the same difficult job no matter when, where or who. The job will always be contentious, and accusations will always be levelled, no matter how efficiently or fairly one attempts to do one’s job. In the face of all of that, all that any policeman can wish for is to be able to “look back on a job well done”.

Bibliography And References With Some Notes

The British Palestine Police Association (Formerly The Palestine Police Old Comrades Association)

http://britishpalestinepolice.org.uk/

Retrieved 2025-08-14.

This website should be the first port of call for anyone interested in the Palestine Police Force. It was an immense help to me when writing this article and I must credit it for much of what I have written here. It does however contain a lot more information than my summary and overview. Its first hand and eyewitness accounts of the historical events provide details that are unavailable in any other literature. The British Palestine Police Association preserves the history of the force, enables former members and their relatives to stay in contact and works on projects involving the repair and maintenance of the graves of British Mandate Police Officers who died because of their police service.

Harouvi, Eldad (2016). Palestine Investigated The Criminal Investigation Department of the Palestine Police Force, 1920-1948. Sussex Academic Press

Mr Harouvi is a military historian and director of the Palmach archive in Tel-Aviv. Specialising in the role of British Intelligence during the Palestine Mandate, he used previously unavailable material when writing this book.

Lehenbauer, Major (US Army) Mark (2013) Orde Wingate And The British Internal Security During The Arab Rebellion In Palestine, Pickle Partners Publishing.

Sinclair, Georgina (2006). ‘Get into a Crack Force and earn £20 a Month and all found. . .’: The Influence of the Palestine Police upon Colonial Policing 1922–1948. European Review of History, 13 (1), pp. 49–65.

One of the better articles on the Palestine Police with lots of facts and figures and details of their role in counterinsurgency. The article also mentions where many of the members went and served after leaving Palestine.

Hughes, Matthew (2019). Britain’s Pacification of Palestine The British Army, the Colonial State and the Arab Revolt, 1936-1939. Cambridge University Press.

Hughes, Matthew (2013). A British ‘Foreign Legion’? The British Police in Mandate Palestine. Middle Eastern Studies, 2013 Vo. 49, No5, pp. 696-711.

Kessler, Oren (2023). Palestine 1936 The Great Revolt and the Roots of the Middle East Conflict. Roman & Littlefield.

Duff, Douglas Valder (1959) Bailing with a Teaspoon. John Long Limited.

Duff, Douglas Valder

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Douglas_Valder_Duff

Retrieved 2025-07-22.

The Palestine Police Force Manual. Palestine Police Force Close Quarter Battle Revolvers, Automatics and Sub-Machine Guns (1943. Reprinted 2008) Paladin Press.

Original copies of this manual are very scarce. Due to interest in combat this manual was made available as a re-print. Unfortunately, it is no longer published and used copies are expensive.

W.E Fairbairn and the Birth of Modern Gunfighting

https://www.firearmsnews.com/editorial/fairbairn-birth-of-modern-gunfighting/453403

Retrieved 2025-07-31.

An article with some background history on Hector Grant-Taylor

Heymans, Brigadier (SAP) HB (2025). 1938: South African Dog Masters in the Palestine Police.

https://www.nongqai.org/1938-south-african-police-dog-masters-in-the-palestine-police/

Retrieved 2025-07-22.

Palestine Police history, thanks to Tony Moore

https://nottspolicedogs.blogspot.com/2009/10/palestine-police_11.html

Retrieved 2025-07-31.

Photos and some details of the Palestine Police dogs

Palestine Police

https://nottspolicedogs.blogspot.com/2009/10/palestine-police.html

Retrieved 2025-07-31.

Photos and some details of the Palestine Police dogs

Guinness world record for the longest scent tracking

https://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/70523-tracking-longest-by-scent

Retrieved 2025-08-10.

The Legend of Sauer

https://www.jockdogfood.co.za/the-legend-of-sauer/

Retrieved 2025-08-10.

The story of Sauer the South African Police tracker dog and his amazing tracking feat.

Palestine Police yearly summary for 1937

https://www.policemuseum.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/PPF1937.pdf

Retrieved 2025-08-10.

This yearly summary provides details of the usage of the Dobermann tracker dogs. It also gives an insight into the force and all aspects of its work at the time.

Green, Gerald (Interview Filmed 2009) The Palestine Police during the British Mandate 1920-1948

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O-ShmqlEjJc

Retrieved 2025-07-22.

Palestine Police Force 1940s British Mandate-Era Recruitment Film

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zSTwLH-UcNA

Retrieved 2025-07-23.

Palestine Police During the British Mandate. Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question – palquest.

https://www.palquest.org/en/highlight/24444/palestine-police-during-british-mandate

Retrieved 2025-07-22.

The Palestine Police Constable’s Manual

https://www.palarchive.org/index.php/Detail/objects/245570/lang/en_US

Retrieved 2025-07-31.

Written by A.J. Kingsley-Heath, the officer commanding of the Palestine Police Training School, this manual was intended for constables in the Palestine section of the force. It covers everything from conditions of enlistment and service through to general police work, criminal procedure and the judicial system.

British Palestine Police Association Centenary of Foundation of the British Palestine Police

Retrieved 2025-07-31.

The Wroughton Silver Band’s News Page

https://wroughtonsilverband.co.uk/index.php/news/

Retrieved 2025-08-10.

Some further details of the centenary celebrations. The band appears to have a close relationship with the British Palestine Police Association.

Kluk, Ephraim (1938) A Special Constable In Palestine, Some Personal Experiences of a South African. Union Publications.

This book was not used by me when writing any of this since, despite my best efforts, I was unable to locate a copy. One is for sale for around 465 Euros putting it well beyond my budget. I have seen it referenced a few times and copies appear to be exceedingly rare. It details the service of a young South African Zionist in the Palestine Police during the Arab revolt in 1938. As such it would be of interest to South Africans. I have added its details here in case someone in South Africa (I have seen mention that there are more copies still around in SA) happens to own or locate a copy and wishes to write a summary for the Nongqai.

Look at the various uniform for each race group….

It reminiscent of what the British had in Shanghai with completely different uniforms, and equipment for the British, Chinese and Sikh members.