Brigadier Hennie Heymans

ROLL OF HONOUR

THE 24 JANUARY 1960 MASSACARE OF POLICE AT CATO MANOR: AN OFFICER’S VIEW

Hennie Heymans

ABSTRACT: On 24 January 1960 a police patrol consisting of nine junior ranks who were engaged in an illicit liquor raid in the Cato Manor shantytown area of Durban were murdered by an incensed mob. This article provides a policeman’s view of that incident, supplemented by contemporary press reporting.

KEYWORDS: 1960 Cato Manor Durban murder of 9 policemen

AUTHOR: Brig H B Heymans

Introduction

It was the year 1960; remember John F Kennedy was not yet president of the US. The US however, had its own problems after the Korean conflict; the Cold War, the “iron curtain”, the Berlin stand-off, racial segregation, the Ku Klux Clan and Vietnam. India became South Africa’s first enemy at the “new” United Nation in 1946[1]. India had obtained its independence from Britain during 1947. Because of our government’s race policy they recalled the Indian Consul-General in Durban. My father had pointed out the palatial Indian office and residency to me, in the Mayville police area.

The “Winds of Change” were slowly but surely sweeping over Africa from north to south! We experienced the 1956 Suez crisis when hundred of ships were anchored before Durban Harbour. The ghastly Belgian Congo massacres were well known to us, as we had a Belgian fugitive in our school. We saw the terrible pictures in the press. This was our second experience of refugees, the first were the Hungarians who fled during the 1956 uprising against the communists there, and some were given refuge in Durban with the Railways.

It was only 12 years before that Dr DF Malan of the National Party assumed power in South Africa. We Afrikaners were not yet over the euphoria. South Africa was then still the Union of South Africa and part of the British Commonwealth. Dr HF Verwoerd was prime minister since 1958. The “Granite” Dr Verwoerd[2] was hated by the English press and working-class English-speaking people in Durban. Durban was an important naval port, and the Union Jack was flying, next to our “oranje, blanje, blou” from the city hall.

As far as the white population was concerned, we Afrikaners were greatly in the minority. We got our first Afrikaans Primary School in Durban during 1953. At first, I attended Stella Park Primary School, in fact an English school with a few Afrikaans classrooms added. We Afrikaners were the children of policemen, railwaymen and civil servants. Most of us belonged to the Dutch Reformed Church. We eavesdropped on our parents and their guests. We picked up titbits here and there – yes, the Afrikaner was moving “upward” but on the other side of the scale the clouds of war and revolutions was on the horizon. But that day, we thought, was far away!

Durban

Durban lies next to the warm Indian Ocean in the Sub-Tropics. Durban is a multi-racial and multi-cultural area: Zulu, Hindu, Boer, Brit, Jew, Christian, Zanzibari and Moslems all mixed together. The then so-called Indian Market in Warwick Ave was a fantastic place. The area was covered in lovely exotic aromas and strange products were exhibited. Here I saw betel-chewing Indian ladies in traditional saris and jewels that pierced their noses. A cacophony of sounds and languages were heard. A bunch of 100 bananas then cost 5/- that is 60 cents!

The Actors

My father was a policeman and he was a raconteur. As and when we travelled in and around Durban, he would point out landmarks of “police interest” and would say “this happened here” and he would love to tell the story… He was in the 1949 Cato Manor riots. My father could speak Zulu fluently and a little of Hindi. My father’s actions made that I came from the wrong side of the Afrikaner ‘cultural railway tracks’. He was a “Bokryer” – a Freemason and during World War 2, he took the “Red Oath”. He was a “Smuts”-man. Both his parents, my grandparents, were victims of the British Concentration Camp policy. They lost siblings in the camps.

So, I knew about the “Cato Manor” incident and the tragedy that had happened there on 24 January 1960. Both my parents insisted that we children become “readers”. We read the English newspapers and the weekly Afrikaans newspaper “Die Nataller”. My father also read the “Post”, then a non-white newspaper. I fell in love with all the newspapers – The Natal Mercury, The Sunday Tribune, The Sunday Times and the Daily News and magazines like the Jongspan, Huisgenoot, Famer’s Weekly and Landbouweekblad. As Afrikaners we loved to read about farming and agriculture.

So, while most of South Africa was “nationalist” a place like Durban (and Pietermaritzburg) was still a safe haven for the English speakers and those who were British orientated. I had English speaking uncles, aunts and cousins. I then knew about the “Torch Commando” of ex-servicemen under the leadership of “Sailor” Malan. It was the days of the Black Sash and the author of the acclaimed book “Cry the Beloved Country”, Alan Paton, lived outside Durban. Our local chemist, Mr Harry Melford Lewis, was the United Party MP for our constituency, Umlazi. Durban still had a few proper English-speaking police officers. We also had a few English-speaking policemen who were transferred from the City Police to the South African Police in Durban.

A ‘champion of the African’s cause’ in Durban was Rowley Israel Arenstein, a lawyer and listed communist. He “cheaply” defended many an accused from Cato Manor. As a lawyer, he was well-known to most policemen in Durban. I was introduced to Rowley, before I joined the Police, by my father, Sgt Heymans. Ironically, he also defended policemen in departmental trails and in court. There was no animosity towards him by the police.

As myself later a member of the Durban Security Branch, I walked down Smith Street during 1970 with a colleague when we met Mr Arenstein who was recently back in Durban. My colleague stopped and he greeted Mr Arenstein, and a friendly chat took place.

| Rowley Israel Arenstein

Born: 1919 Died: 1996 In summary: Lawyer, banned person, trade union advisor, member of the South African Communist Party and Congress of Democrats, advisor to Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi. Rowley Israel Arenstein was born in 1919. Arenstein was a prominent Durban attorney and a leader of the Congress of Democrats (COD). He joined the Communist Party in 1938, becoming an organizer for the Durban and District branch. In 1947, he withdrew from active politics to concentrate on his legal practice, but he did participate in the Durban branch of the COD in the 1950s. In 1950, following the Suppression of Communism Act, the South African Communist Party (SACP) decided to disband (though an underground SACP was soon set up). Arenstein worked closely with Chief Albert Luthuli and Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi. Buthelezi had been expelled from Fort Hare University for his African National Congress (ANC) activities and had come to work at the Durban Commissioner’s Court, the administrative experience being thought useful to the future chief.[3] Arenstein and Buthelezi became close friends. Buthelezi became one of Rowley’s articled clerks. When the chieftaincy of the Buthelezi clan was offered to him, Rowley helped Buthelezi defeat an early challenge to his chieftaincy and became his legal adviser. Arenstein was first barred from political activities in 1953 when he banned. During this period, he was active in organizing opposition to the new laws enforcing apartheid and in establishing labour unions in Durban. Arenstein suffered the longest period of banning (33 years) in South African history and endured the longest house arrest (18 years), with his wife Jackie not far behind: she was house-arrested for six years, banned for 19. His wife, Jacqueline Arenstein, a journalist, was a defendant in the 1956 Treason Trial. Though banned, he continued to defend persons accused of political offences. Among the ANC activists with whom Buthelezi mingled at the Arenstein house were Nelson Mandela and Walter Sisulu – who always visited Rowley when they came down to Durban to visit Luthuli. Rowley found himself becoming increasingly critical of the autocratic style of the Johannesburg-based Communists who ran the underground SACP and, through it, the ANC. In 1960 with the Pondoland insurrection against the Government-imposed Bantustan policy, the Pondos were fiercely suppressed and turned to the Arenstein for help. At least 11 people were killed and 6o wounded. Four months after the dead were buried; their remains were exhumed at his insistence after he challenged police claims that fewer than 11 people were killed. Arenstein was barred from leaving the magisterial district of Durban on 1 October 1960 and subsequently could not represent his clients. He had to go to Pondoland to defend them – many of the Eastern Cape Communists had been detained. When he got back to Durban, a delegation of Pondo leaders came to see him requesting that he facilitates a purchase of guns. Arenstein was able to convince them otherwise and dissuade them from embarking on a violent course. In 1961, he led the legal fight for the release of Anderson Ganyile and other leaders of the Pondoland revolt who had been seized in Lesotho by the South African Police (SAP). He was vociferous in opposing the move to the armed struggle, predicting that it would bring catastrophe to both the SACP and ANC. During this period, Arenstein claims that he resigned from the Party, although the party insisted that he was expelled. Arenstein was detained without trial in 1964 and went on hunger strike and was released. When Bram Fischer went underground in 1965, one of the first things he did was to re-establish links with Arenstein, in Natal and Fred Carneson in Cape Town. In 1966 he was sentenced to four years’ jail under the Suppression of Communism Act for furthering the aims of Communism. The prosecution failed to pin a charge of belonging to the SACP. In jail, he developed a strong friendship with the SACP leader Bram Fischer whom he held in very high esteem. In 1970, Arenstein emerged from jail to find that the ANC had been so utterly smashed that it had effectively ceased to exist within the country. When the Government offered Buthelezi the post of Chief Minister of KwaZulu he sought Arenstein’s advice, and that of the exiled ANC. Both agreed that he should accept– but refuse to take independence. In 1971, Arenstein remained struck off the official list of attorneys – a punitive measure by the Government which had been in force for twenty years – and was forced to practise from modest offices disguised as a ‘business adviser and consultant’. Although he remained banned he assisted the Defence in the Pietermaritzburg trial of 13, charged under the Terrorism Act. He was later banned from practicing law and placed under house arrest in Durban. He spent the early seventies as an adviser to trade unionists when moves were being made to build up a black labour organisation. He was also a legal advisor to the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP). In 1988, despite the vehement protests of the Government, Buthelezi nominated Arenstein as one of his negotiating committee with Pretoria. Thus, Arenstein also served as a legal advisor for the Inkatha Freedom Party. When Winnie Mandela was denounced for her association with the Mandela United Football Club, Arenstein offered to help her, an offer which she accepted. After Mandela was released, Arenstein phoned him and told him that the political violence between the ANC and Inkatha in Natal had to be stopped, and that to achieve this he had to meet Buthelezi. Mandela agreed and told him to arrange such a meeting. The Inkatha stronghold of Taylor’s Halt was chosen as a venue. However, the meeting did not take place but eventually, Mandela and Buthelezi met. The Arensteins had two children and lived in Durban. Arenstein died in 1996. References · Gerhart G.M and Karis T. (ed)(1977). From Protest to challenge: A documentary History of African Politics in South Africa: 1882-1964, Vol.4. Political Profiles 1882. · SADET, (2004). The Road to Democracy in South Africa Volume 1 (1960 – 1970). Cape Town, Zebra Press. · Johnson, RW. (1991). Rowley Arenstein, friend of Mandela, supporter of Buthelezi, talks to R.W. Johnsonfrom the London Review of Books, [online], Available at www.lrb.co.uk [Accessed on 4 November 2011] .[4].

|

As far as policy is concerned, there could have been a lot of conflict between a United Party controlled-Durban and the Nationalist government in Pretoria. Picture this: Durban had its own police force, the Durban City Police (a former borough police dating back to colonial times). Durban had its own telephone exchange and its own municipal power station – they were a lot of independent fellows back then, if you asked me. Natal later voted in the 1960 referendum against the Union of South Africa becoming a republic.

Here are the results of the 1960 referendum[5]:

| Province | For | Against | Invalid/ blank |

Total | Registered voters |

Turnout | ||

| Votes | % | Votes | % | |||||

| Cape Province | 271,418 | 50.15 | 269,784 | 49.85 | 2,881 | 544,083 | 591,298 | 92.02 |

| Natal | 42,299 | 23.78 | 135,598 | 76.22 | 688 | 178,585 | 193,103 | 92.48 |

| Orange Free State | 110,171 | 76.72 | 33,438 | 23.28 | 798 | 144,407 | 160,843 | 89.78 |

| South-West Africa | 19,938 | 62.39 | 12,017 | 37.61 | 280 | 32,235 | 37,135 | 86.80 |

| Transvaal | 406,632 | 55.58 | 325,041 | 44.42 | 3,257 | 734,930 | 818,047 | 89.84 |

| Source: Direct Democracy | ||||||||

We had contact with Sgt “Oom Curt” Scheepers who was stationed at Cato Manor. Please allow me to digress for a moment: I should also mention that Constable Gys Muller was a friend of my father. When I “passed out” as a Constable during June 1964 he came to our home, and he congratulated me on my appointment as Constable. Years later I was District Commissioner of Police in Welkom and met Oom Gys Muller at a Civic Reception for Mayors from all over South Africa who had gathered there in Welkom. Oom Gys Muller had, in later years, become Mayor of Durban under National Party rule. In days of old it was not uncommon for some Durbanites to ask a policeman to call at the backdoor!

So much for change in my lifetime!

Locality

Inland (generally westwards) from Maydon Wharf you would find Port Natal Primary School and behind the school on the ridge was the Natal University – Howard College and the Memorial Tower Building. The Medical Faculty of Natal University had their offices and lectures rooms right in front of our school in Umbilo Rd – south from the then King Edward Hospital. Steve Biko was a student here. In the hollow behind the university’s Howard College you would find Cato Manor – named after Durban’s first Mayor George Cato.

Cato Manor “was named after … George Christopher Cato. In 1843 the land which later became Cato Manor was given to him as compensation for another portion of land previously used for military purposes. It was also intended as a reward for his years of personal dedication to community service and recognition as Durban’s first Mayor in 1865.”[6]

Cato Manor was about 5 miles or 8 km away from the city centre – by far the closest “non-white” residential area to the workplaces in the CBD, the port, industrial areas and white residences.

As far as I could see, Cato Manor was even then a keg full of explosives – waiting for the right catalyst to explode at any minute. Various riots took place there – the newspapers were full of it. Major Jerry van der Merwe once appeared on the front page with a bleeding face after a stone was thrown at him, which struck him in the face. All the factors and actors were present, especially over weekends. Various factors were at play. It was just a question of time.

Cato Manor was not far from the Durban harbour, not far from Maydon Wharf and not far from the factories and industry. The proud Zulus became urbanised. Due to a housing shortage, they were forced to become squatters in that area, mostly renting from Indian landlords. Conditions were not of the best, and in 1949 Cato Manor was one of the focal points of the deadly Zulu pogrom against Indians. The NP government had, therefore, resolved to “clear up” Cato Manor in terms of the Group Areas Act. To re-house black residents the sprawling new KwaMashu township was established. The home were much better, but the commuting distance to work was far greater, so that the forced removals from Cato Manor had been contributing significantly to the resentment that had creted the “powder keg” atmosphere.

In addition to the resentment about forced removals to KwaMashu township, most “whites” at that time did not appreciate the social and cultural importance of indigenous brewed beer. With industrialisation many Zulu men from the rural interior migrated to the city to earn a living. Often they would live in company hostel compounds. Money was needed back at home, and many a wife would risk the influx control regulations (“pass laws”) and come to Durban to look for her husband and his money.

Zulu women, like all Nguni womenfolk, were able beer brewers. African beer is also very nutritious. (It should also be remembered that at the behest of the Rand Lords “white” liquor was not sold to Africans. They had traditional beer and illicit brews like skokiaan, itisjimijane and gavine.)

A conflict of interest arose between the Durban City Council who had its own beer halls where they sold traditional beer and used the profit to uplift the Africans. These municipal halls were bleak structures reminiscent of the hostels which the workers were seeking to escape when they went drinking, craving an ambiance in sync with their own culture. On the other side was “free enterprise” – the traditional brewers. Their trade which they had practised since time immemorial was thus criminalised, essentially to protect the municipality’s monopoly. It was a conflict between “new” legislation and indigenous custom. It is just here where a problem arose between the South African Police – enforcers of an unsympathetic law, the Liquor Act, with regard to which the local borough police did not have jurisdiction – and the informal brewers who ran their own shebeens and sold liquor to survive, providing the workers with a culturally familiar environment in which to relax. In this regard many a sympathetic policeman experienced this difficult situation of inner conflict between his duty and his conscience. Many brewers, in order to survive, became police or detective’s informers of murder, robbery, stolen property and drugs etc.

1960.01.24: MASSACARE OF POLICE AT CATO MANOR

The following members of the Force were murdered at Cato Manor on Sunday 24 January 1960:

- No 119702 2nd Class Sergeant K. Buhlalo

- No 36446 Constable C.P.J.S. Rademan

- No 35490 Constable G.J. Joubert

- No 36496 Constable L.W. Kunneke

- No 34624 Constable C.C. Kriel

- No 133633 Constable P. Jeza

- No 130543 Constable F. Dhludhlu

- No 134706 Constable M. Nzuza

- No 136349 Constable P. Mtetwa

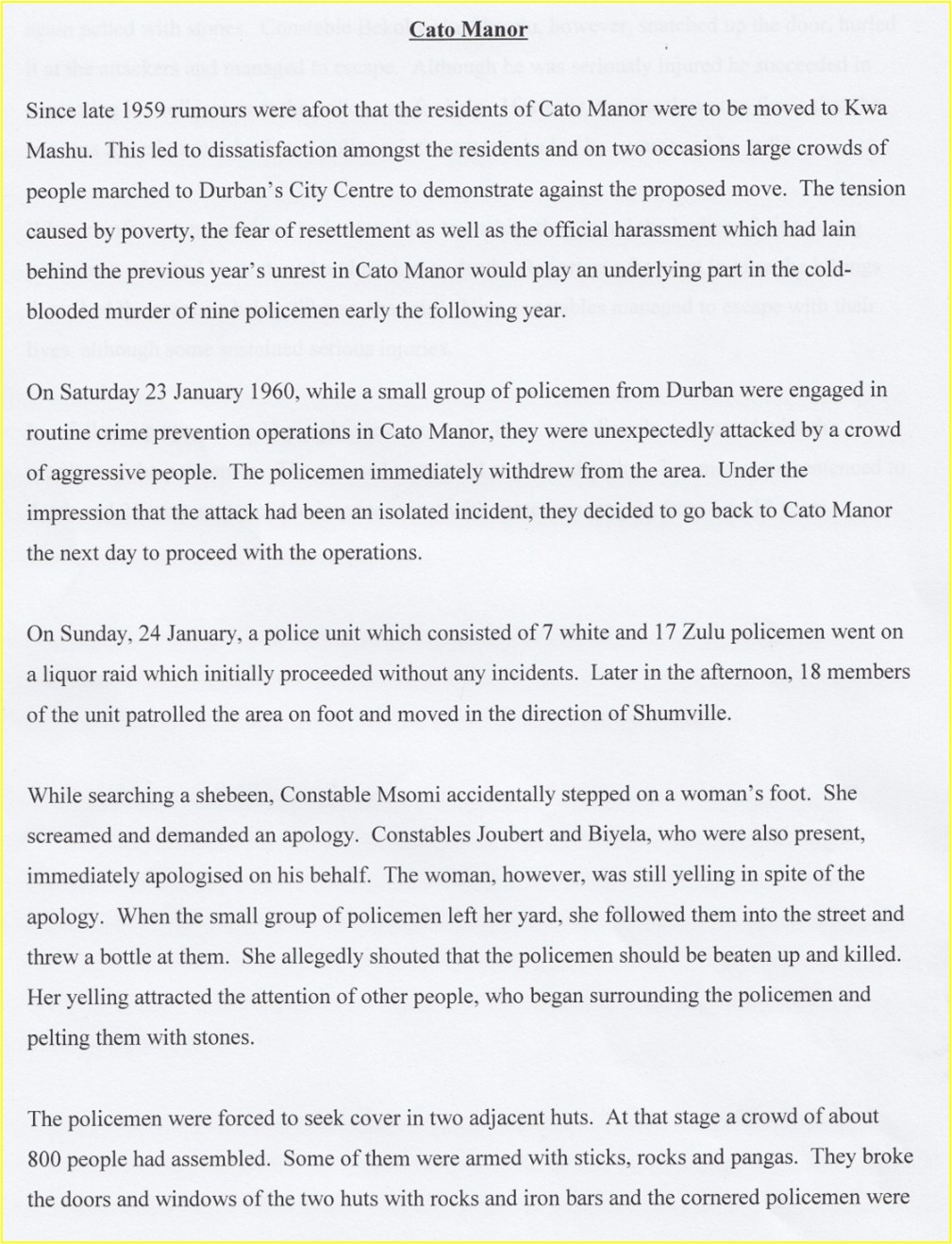

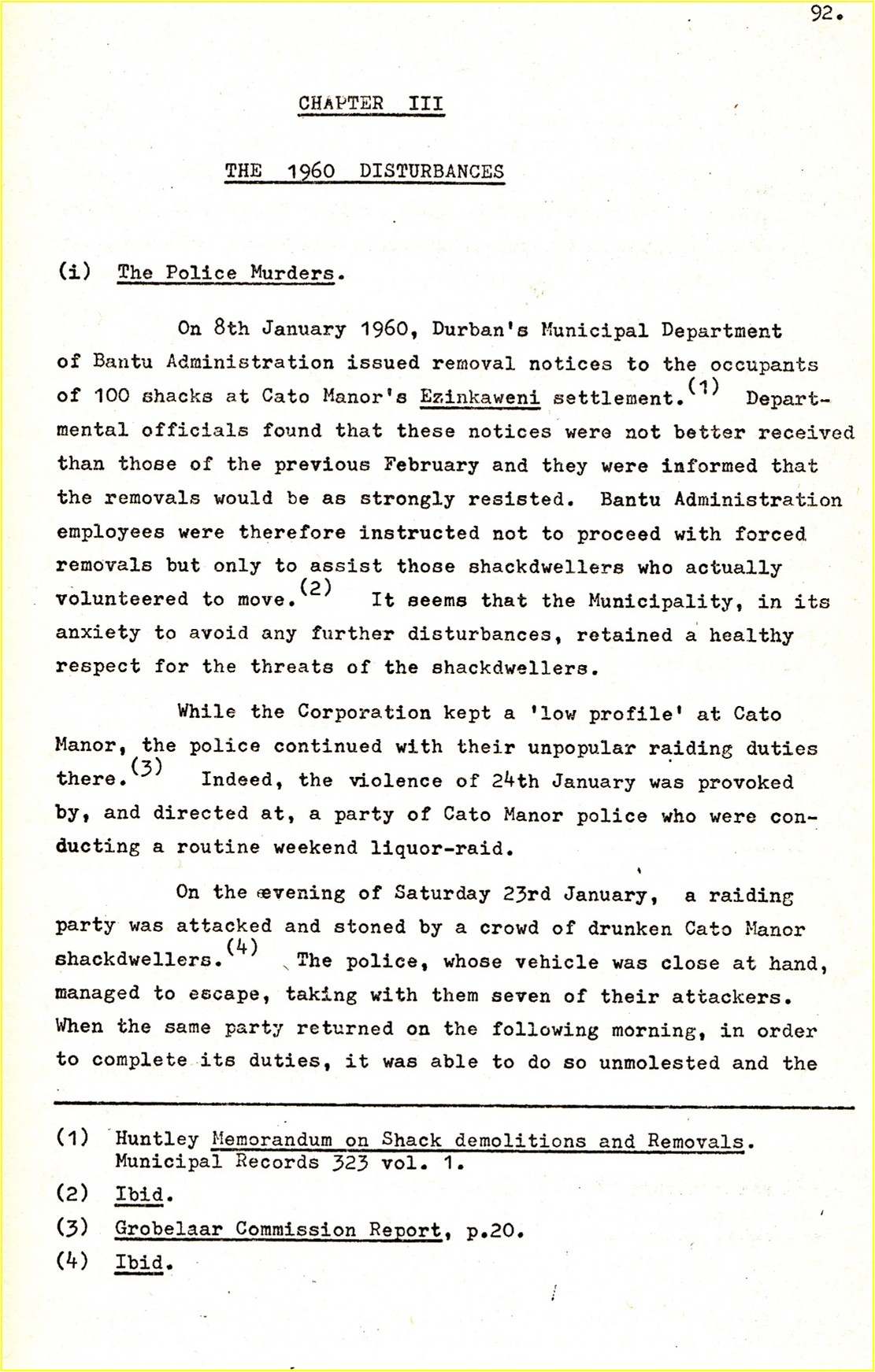

The official police version, vide SAPS Museum File 667-29/2/1B- 6/14-1, is as follows:

News from Port Natal: The Nongqai, March 1960

|

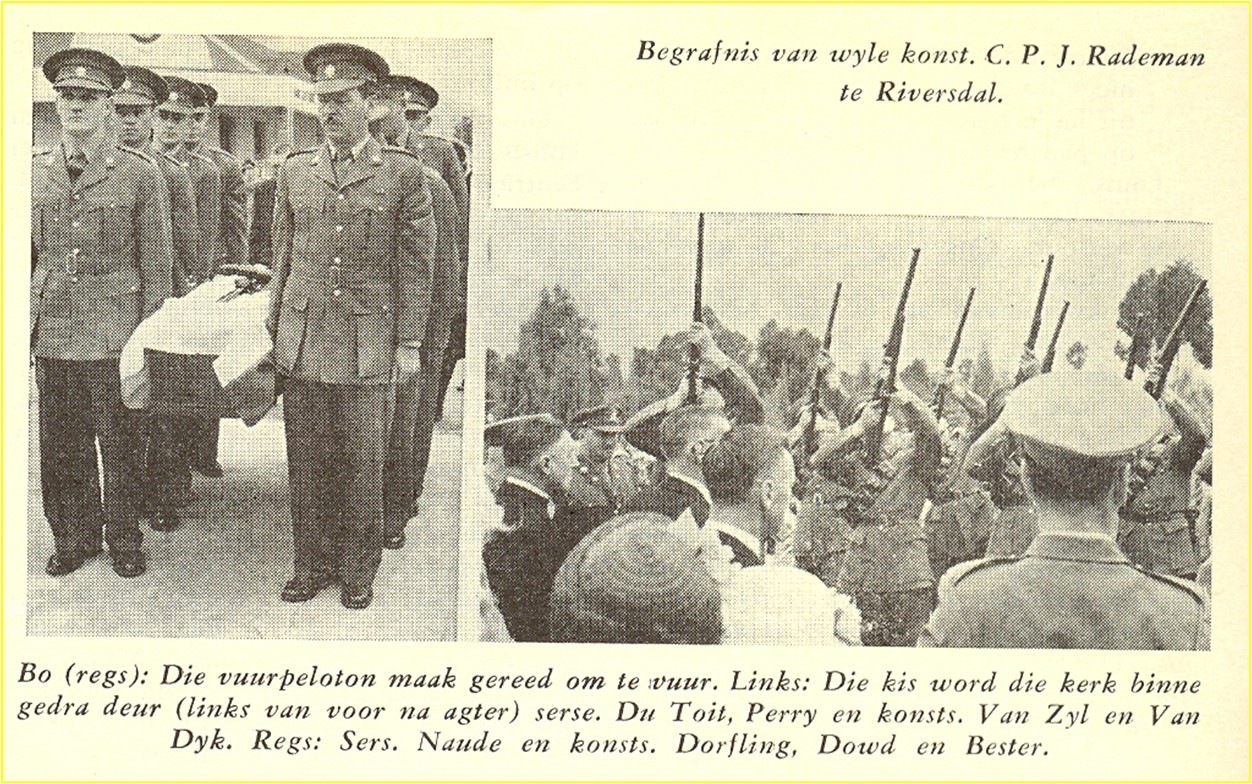

Riversdale

As a young policeman I listened to the stories told by my elder peers about Cato Manor. Later in life when I got much more interested in “police history” I spoke to a detective, Lt-Col Daan Wessels, and asked him before his death how the murders of the policemen were investigated? He told me each murder was investigated separately. He was the investigating officer of one of the murders. He also told me that “Kwa-Ticky” was a place where you paid 3d (21/2 cents) per night for a bed. Nearby a group of traditional beerdrinkers were sitting under a tree enjoying their “sun downer” when a policeman rushed by. They apprehended him and killed the poor unfortunate policeman. While the whole case was investigated the same group congregated under the same tree, before they could be apprehended, lighting struck and killed them all. The locals said it was the spirits who called for the innocent policeman’s blood!

Cato Manor and the Press

Our readers might find it interesting to see how an eminent journalist, Mr Harvey Tyson, saw the matter. After all these years (1993) I think he has presented an objective and sympathetic view of a difficult case[8].

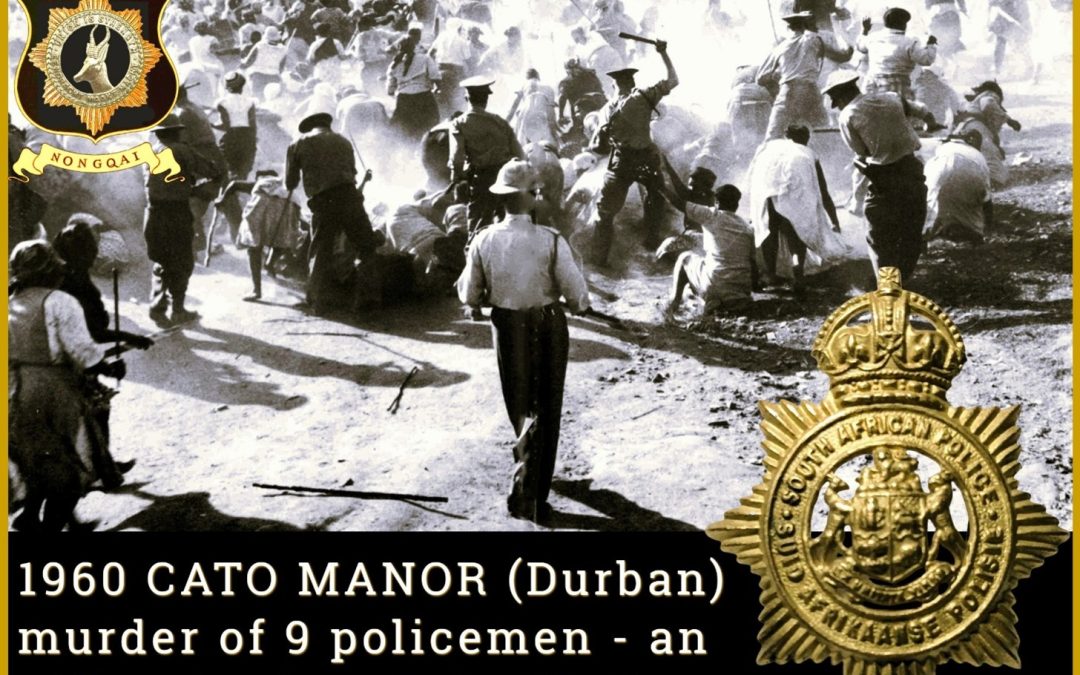

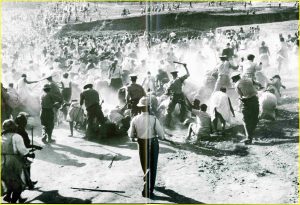

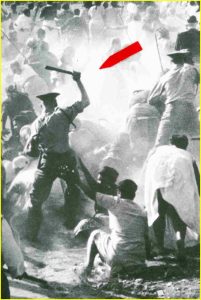

| “The emotional and political power of this news photo transcended the dust and the reality of the day.” – Harvey Tyson

Laurie Bloomfield, a photographer of the Daily News in Durban received co-operation from Major Jerry van der Merwe of the SA Police. The Major wanted the police action recorded on film mainly to show how the police under his command were hugely outnumbered. We count eight policemen against a large gathering. He wanted to show how the police tried the principal of minimum violence and that the SAP without having to resort to fire-arms, performed instead a baton charge to disperse the crowd. This was a volatile situation facing the police.

So, the picture at the request of the SAP had an ironic twist: In years to come (post 1960) this photograph became world famous photograph; an icon portraying “police suppression” and a “police state” in Apartheid South Africa. |

Harvey Tyson writes: “Cato Manor was the key to the problem. It lay out of view of Durban and not easily noticed from the university on the hill dividing the bay from the overcrowded valley. Cato Manor, hidden and neglected, was notorious for its squalor and its inflammability.”

Just more than a decade after the first Cato Manor riots[9] a policeman, part of a police raiding party, stepped on a woman’s toe while searching a shebeen. He should not have done that, as it served as a catalyst for a new riot on that Sunday afternoon. Among the same crowded Cato Manor shanties, police made arrests for illicit possession of liquor, and on 24 January 1960 the umpteenth riot broke out. This riot shocked South Africa! Nine policemen were dead! The Daily News reported that a black police sergeant and four very young white constables and four black[10] constables were murdered:

With 24 bullets among them, a police raiding party fought the horde of rioters until their ammunition ran out … Three 19-year-old European constables, trapped in a bungalow, were massacred by the mob who broke the doors and windows with rocks and iron bars. Three Native constables were hacked to pieces and mutilated beyond recognition. The fourth European constable ran about 400 yards before he was brought down by the mob and bludgeoned to death. The bodies of two more Native constables were found nearby.

Empty shell cases found in the rooms today indicate the desperate battle the policemen put up until their ammunition ran out. It was every man for himself after the white constables had emptied their revolvers into the mob. One by one, the policemen leapt through doors and windows. Of the 13 who escaped, three were badly injured… [11]

“The public – and the press – yearn to know ‘the cause’ of every major tragedy. ‘The cause’ is most often a minor incident, a trigger in fact. The real cause of trouble in Cato Manor included all the worst aspects of apartheid: unresolved tensions arising out of poverty; insecurity of tenure; official harassment. More than 125 000 people lived in the 4 500-acre shantytown. The land was owned by Indians, and their Zulu tenants sub-let to sub-tenants who built shelters out of anything they could lay their hands on. Many women in Cato Manor survived by brewing beer illicitly. They and their families, who had traditionally always brewed beer at home, tried to bum down the official beer halls. The police in turn tried to destroy the illegal shebeens”[12] writes Tyson.

Women led the defiance and, as the political historian Tom Lodge reports, ‘in some instances anger was effectively mixed with ribaldry and sexual assertion’? He quotes researchers as saying:

‘These women were very powerful. Some came half-dressed with their breasts exposed, and when they got near this place the Blackjacks (municipal police) tried to block the women. But when they saw this, the women turned and pulled up their skirts. The police closed their eyes and the women passed by and went in … and they took off their panties and filled them with beer… ,[13]

It was the women who led the rioting in Cato Manor in January 1960. One of the world’s most famous photographs symbolising oppression was taken during those riots by Daily News photographer Laurie Bloomfield. He was standing on a hillside in the light of the setting sun as a thin line of policemen, afraid but angry at the slaughter of their colleagues, advanced on a crowd. Consisting mainly of women, the crowd had created a penumbra of dust as they danced and ululated, as generations of Zulu women before them had done to encourage their men in battle. Bloomfield snapped his picture as a policeman raised a baton high before bringing it down on someone in the crowd.

To prove their case, it was ironic that the police in the absence of an official police photographer asked a journalist to take photographs. Bloomfield says there were about 30 policemen facing a large crowd of angry Zulu women and youths. Tyson quotes Laurie Bloomfield who described the events as follows[14]:

The policeman in charge – not very senior, but an officer with a fine reputation by the name of Van der Merwe[15] – came over to me and said that he and his men were about to make the first baton charge of their lives. They required a recording of it. What would I need in order to get such a record on film? Those were the days!

I told him: ‘I want to stand on the roof of that big truck of yours, but it must be repositioned here.’ This was done, and I felt as though I was in charge of a production. It was like a movie set.

The police commander said: ‘We’ll issue a third and final warning to disperse, then if nothing happens, we’ll count down from 30 and then make the charge, so be ready with that camera. Then the police, black and white, started to run at the crowd. They cracked five or six heads, but mainly whacked the fleeing women on the buttocks, and the whole crowd turned and ran. There was very little violence … until after dark.

Bloomfield’s photographs were hugely dramatic and seemed to have captured the very essence of conflict, tension and police violence.

The photographs had quite the opposite effect from the one expected by some well-intentioned, well-drilled police who refrained from using fire-arms. The one iconic photograph went instantly around the world. The particular photograph appeared on the front page of every Argus newspaper and almost every other newspaper on earth which had access to Associated Press but with one exception: Bloomfield’s own paper, the Daily News.[16]

Acting as editor of the Daily News, in the absence of JSM Simpson, René de Villiers, however decided not to print the dramatic picture in the Daily News. René de Villiers felt it was too emotionally explosive to publish the dramatic picture in the heat of a riot. His staff was astounded.

“Had it been anyone other than De Villiers taking that decision – had it been the editor – there might have been a riot in the newspaper. We were ready to cry ‘unethical censorship’, even ‘cowardice’; but it was hard to accuse De Villiers of these. His sympathy for the oppressed and his credentials as an honest newspaperman was greater than those of his accusers. We realised, too, that the easiest decision for him – one with no personal consequences whatever – would have been to publish the picture. Instead, he chose the toughest option and the worst in terms solely of his own interests”, writes Tyson. [17]

“That picture is so strong it will lead to more riots and perhaps many deaths if it goes into Cato Manor tonight. Let them publish it in Johannesburg and Cape Town”, said René de Villiers. Tyson concludes: “Few of us were convinced by this but we accepted his view.” [18]

At that stage my father was a policeman at Somtsue Rd in Durban. They were on standby at their station. We did not see him often. I clearly remember the SA Navy had search lights on during the night at Cato Manor. From the Bluff we saw the search lights prying into the night sky and clouds.

Later I was employed on the “Communist Desk” at SAP Security Branch Head Office in Pretoria and I can confirm that the same iconic photograph was used over and over to our disadvantage. I must confess it was an excellent shot and it did much to tarnish the image of the South African Police. Tyson remarks: “The Communist Party, from Britain to Bolivia, from Moscow to Mexico, used Bloomfield’s picture as a poster and almost as a logo (without acknowledgement or payment, of course).”[19]

As far as political warfare went, we were novices. At that stage we did not have a public relations division or “Stratkom” or “Psy-Ops”. We had to wait at least another decade for a public relations division and two decades before we used “Stratkom”.

On the other hand, Cato Manor was a tough place – the Zulu, like the Afrikaner, were good fighters. Actually, we were much the more the same, than we differed.

The Academicians

Conclusion

It is always easy to be an armchair judge of such an event! Many liberals, academicians and journalists have criticised the police in the past.

Commment

The police are not above criticism. I have one aspect of criticism against the defunct South African Police Force: Maybe because we were understaffed; but I think our inspectorate should have done an internal enquiry into disasters like Cato Manor. But we were far too busy with our 24-7-365-job! More lives could have been saved if we did more honest introspection. I believe we did not learn any lessons here.

From my personal viewpoint regarding riots: Not everything is apartheid’s fault. I have served as a youngster, and I have served as a commander who gave orders. It is no easy task; no amount of academic knowledge helps you, its experience that counts when you are confronted by a dangerous hostile mob! Sometimes you are in a catch-22 situation. You are damned if you do and dead if you don’t!

You must know how to read the crowd like a book! Usually, the best sounding board is one of your elderly traditional African policemen who know the chants and the songs! Who reads their body language like an open book! Never show fear! You must stand fast before such a crowd, fearless, but not unnecessarily provoking them either. Your focus must be on de-escalation, on avoiding situations that can lead to confrontation. I have found that humour can defuse a situation, but then we are not clowns but enforcers.

The two fiercest groups of fighters I have experienced are mineworkers fighting their faction fights on the Free State gold mines and the Zulus. The Zulus are the worst and the fiercest fighters and they sometimes love the fighting! (A Zulu police lawyer once said to me in Ulundi: “You know what we have in common with the British? We love a good fight!”)

We as police actually not only have to face the hostile mob, but when things have cooled down: Inquests, Commissions & Judges like Judge Goldstone. Both the fighting and the aftermath can be frightening experiences!

With the Zulu their womenfolk are nearby, ululating, dancing with swaying breasts and buttocks giving rise to high testosterone levels amongst the attackers. It’s like a baseball game with unwritten rules. Such noise is deafening! Dogs – both police and local – barking, children crying, people singing, the stamping of feet and chanting, toy-toying, sirens of ambulances and fire brigades and police choppers hovering overhead. The police commander must be cognitive and situationally aware. He must be wide awake even after a long shift, he must take in everything and decide if and when is the right moment to take counter action within the realm of the law, if unavoidably necessary! And not only whether he should take action, or when – but also, what kind of action would be appropriate in the circumstance.

The academic can retreat to his ivory tower and take time to decide where blame lies. Unfortunately blame sometimes lay with the police because they are in the first-place humans, secondary they are the primary executive organ of the state and they are perceived as the enforcers of “bad laws”.

During 1966 I performed “special duties” in Umlazi. I had to work from 6pm until 2 am with a group of African policemen. When we came to a section called “Mplankweni” – the place of Plank Houses – the African Constables said to me: “Be careful here – these people were moved from Cato Manor, and they live in plank houses hastily erected to accommodate them. They can be dangerous!” So, one has to take note and be careful and vigilant.

A policeman’s lot is not always a happy one. It is difficult for the police to say “they are sorry” because through a legal eagle’s eyes that may amount to an admission of certain acts committed by the police. This “no comment” causes a gulf between the police and their clients, the community at large.

We take a moment to pause and to think of those policemen and civilians who paid the highest offer in Cato Manor.

I venture to say that Natal policemen, especially those who grew up with the Zulu and knew their culture and language such as my Security Branch commander Colenel (later Major-General) Frans Steenkamp, had taken the lessons of the 1949 Zulu/Indian pogrom and the 1960 Cato Manor tragedy to heart, when the 1973 Durban strikes broke out and presented a far greater potential danger to public order. Consequently, those 1973 Durban strikes were expertly handled, with no loss of life – thanks to good intelligence and superb situational awareness on the part of the police (see our Nongqai Blog article: THE WIDELY PRAISED POLICE HANDLING OF THE 1973 DURBAN STRIKES – Nongqai BLOG )

Unfortunately, not all commanding officers had learnt those lessons – as was tragically seen at Soweto on 16 June 1976, creating a watershed moment in our country’s history that is now widely seen as the turning point that heralded the coming end of Apartheid,

Reading through my old school’s anniversary edition, 1953 – 1978, I came across the Afrikaner’s struggle for Afrikaans schools in Durban. That is a subject for another day but found it ironic that a decade and a half later we imported and forced Afrikaans into Soweto Schools, like the British did with us after the Anglo-Boer War. In June 1976 in Soweto this act exploded in our faces and once again the “poor” police bore the brunt of the people’s anger! The Soweto Riots gave such an impetus to the struggle and the revolutionary war that the SACP-ANC Alliance could hardly believe their luck! This action was planned by clever people, but it just proves that not everybody learns from history!

Sources

- Feesblad: Laerskool Port Natal: Die Anker (1953 – 1978) No 20 dated 1978.

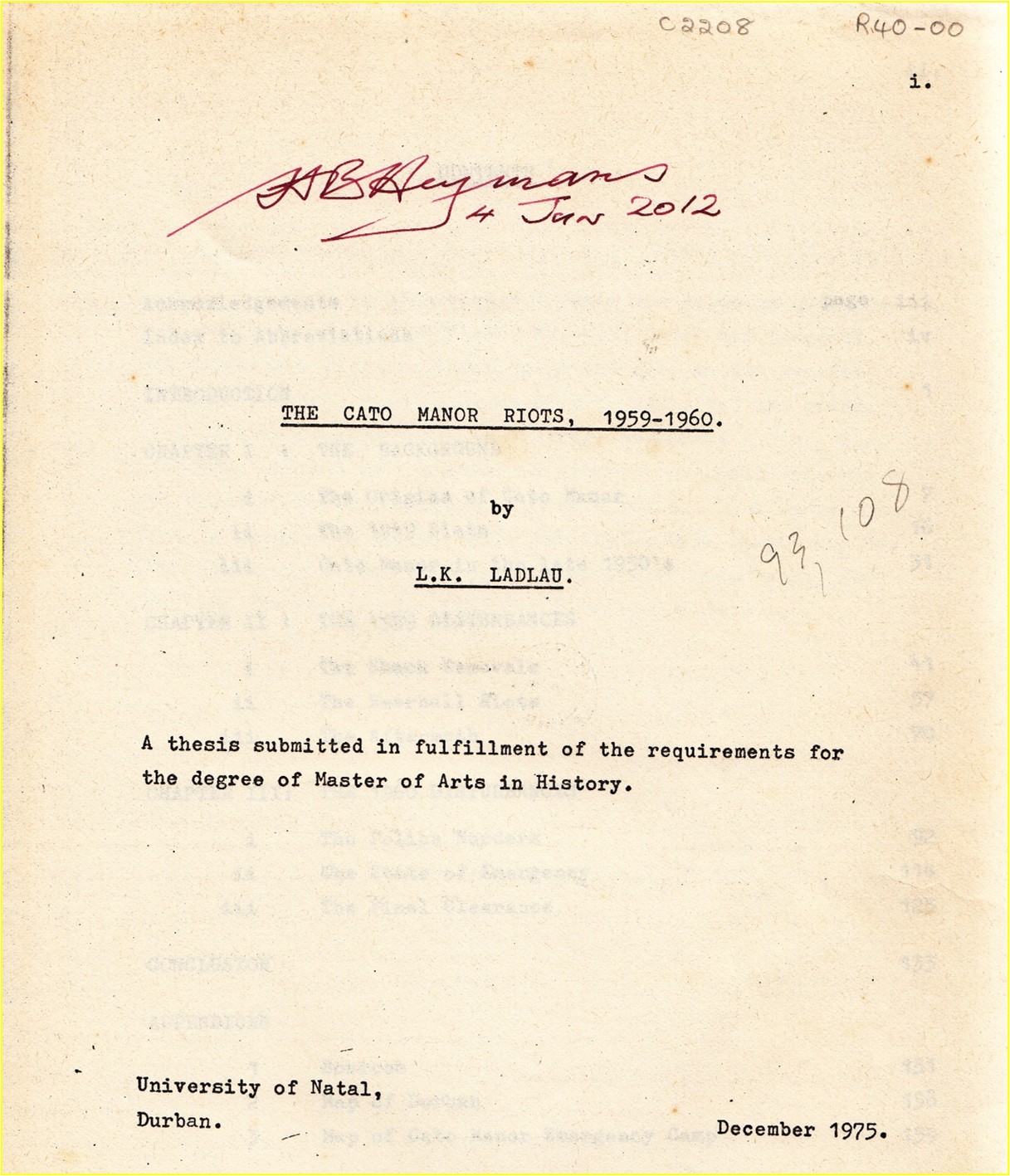

- Ladlau, LK: The Cato Manor Riots, 1959 – 1960, (MA Thesis) University of Natal, 1975.

- The Nongqai, March 1960.

- Tyson, H (1993): Editors Under Fire. Sandton: Random House (pp 70 – 73).

References

[1] “The world did not, however, condone South Africa’s discriminatory policies. At the first UN gathering in 1946, South Africa was placed on the agenda. The primary subject in question was the handling of South African Indians, a great cause of divergence between South Africa and India.” – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Foreign_relations_of_South_Africa_during_apartheid (Accessed 18th of March 2015)

[2] I remember one cartoon: “Verwoerd, Verward, Verwarder.” But he was definitely not liked by the English speakers on the Bluff, the part of Durban where I grew up. – HBH

[3] My father had an complaint against a certain member of the Buthelezi-clan and my father wrote to Dr Mangosuthu Buthelezi who in his reply mentioned he remembered my father from Durban and the contact they had while he was attached to the Commissioner’s Court in Stanger Street, Durban – HBH

[4] http://www.sahistory.org.za/people/rowley-israel-arenstein (Accessed 18th of March 2015)

[5] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/South_African_republic_referendum,_1960 (Accessed 18th of March 2015)

[6] http://www.sahistory.org.za/places/cato-manor (Accessed 18th of March 2015)

[7] Die Anker, 1978: 36

[8] Tyson 1993: 70 – 73

[9] Riots of January 1949 – HBH

[10] Tyson 1993: 70

[11] Daily News 25 January 1960

[12] Tyson page 71

[13] Organise or Starve: The History of SACTU by Ken Luckhart & Brenda Wall [Lawrence & Wishart, London, 1980.] quoted by Tyson.

[14] Tyson page 71

[15] Then Major Jerry van der Merwe – HBH

[16] Tyson, 1993; 72

[17] Tyson, 1993; 72

[18] Tyson, 1993: 72

[19] Tyson, 1993: 72

*

Brigadier Hennie Heymans, Editor-in-Chief, Nongqai

*

Excellent article; in-depth research and the facts of a difficult period in the history of the South African Police accurately presented. Well done!

Thank you, Sir!