South African Police in Kenya

THE SOUTH AFRICAN POLICE IN KENYA DURING THE MAU MAU EMERGENCY: A TRANSNATIONAL POLICING CASE STUDY

HB Heymans

Introduction

The Mau Mau Emergency (1952–1960) in Kenya remains a landmark anti-colonial conflict. Although primarily framed as a British military and intelligence response to Kikuyu resistance, contributions from other Commonwealth nations are notable—among them, South Africa’s role through its police force. The involvement of the South African Police (SAP) in Kenya reflects a broader strategy of colonial solidarity and knowledge exchange during this volatile period (Elkins, 2005; Bennett & Mumford, 2014).

South African Police Deployment: Scope and Nature

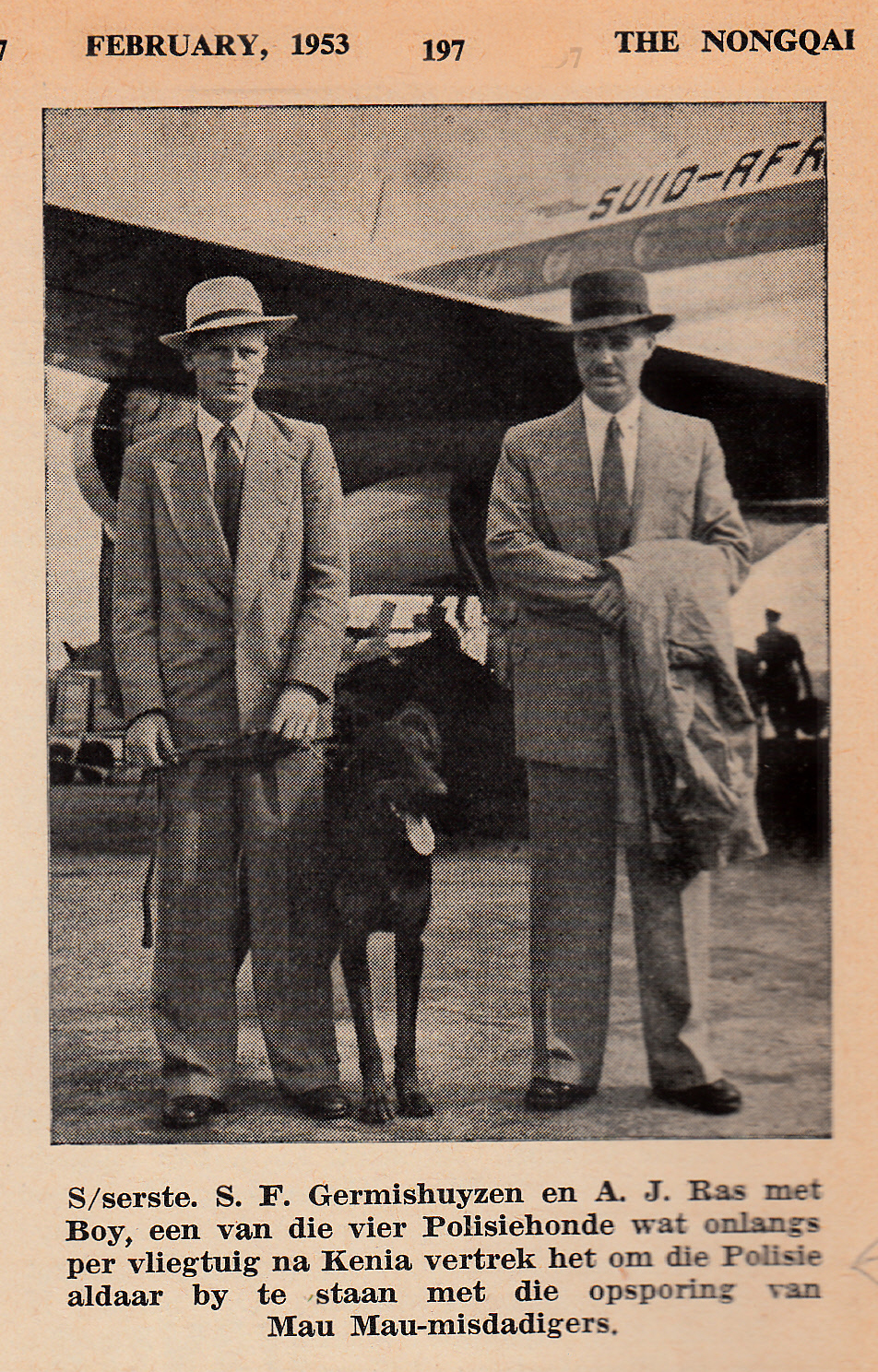

While SAP involvement was limited in scale, it was critical in specialized functions—especially intelligence gathering and canine tracking. In 1953, two SAP dog masters were deployed to assist British forces in forest operations, leveraging South African experience in rural surveillance and manhunting (Bennett & Mumford, 2014, p. 92). These operations took place in the Aberdare and Mount Kenya forests, where Mau Mau fighters had entrenched themselves.

Further, Special Branch officers Van Zyl and Heine were dispatched to aid British intelligence efforts. Their expertise in subversion monitoring had been cultivated during South Africa’s own internal security campaigns. According to Elkins (2005), South African officers played a quiet but impactful role in interrogations and tactical analysis, influencing the development of counterinsurgency models that mirrored South African-era policing strategies.

Intelligence, Pseudo-Operations and Colonial Knowledge Transfer

South African input was not merely operational—it carried intellectual weight. Methods like pseudo-gangs, where loyalist Kikuyu were disguised as Mau Mau to infiltrate insurgent networks, were bolstered by SAP experience (Bennett & Mumford, 2014). These psychological operations prefigured similar tactics used later in Rhodesia and South Africa.

Moreover, interrogation techniques, including psychological manipulation and forced confessions, became a shared lexicon among Commonwealth police forces. Elkins (2005) argues that these methods were part of a systemic structure of colonial repression, whose legacies were deeply felt long after decolonization.

Geopolitical Implications and Legacy

The SAP’s role in Kenya exemplifies the interconnectivity of colonial policing. Personnel, tactics, and ideology travelled across borders, constructing a framework for suppressing dissent across the British Empire. South Africa’s participation also underscored its alignment with imperial priorities during a time of rising African nationalism.

The Mau Mau Emergency became a crucible of counterinsurgency doctrine, and SAP’s contributions helped shape future policy in South West Africa (Namibia), Rhodesia, and South Africa itself. These cross-border lessons reflect not only tactical evolution but ideological reinforcement of white minority rule and anti-communist policing strategies.

References

- Elkins, C. (2005). Imperial Reckoning: The Untold Story of Britain’s Gulag in Kenya. New York: Henry Holt.

- Bennett, H., & Mumford, A. (2014). Policing Insurgencies: Cops as Counterinsurgents. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- “Mau Mau rebellion.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mau_Mau_rebellion

- Kenyan History Archive. “Mau Mau Uprising in Kenya – 1952–1960.” https://kenyanhistory.com/2025/06/17/mau-mau-uprising-in-kenya-1952-1960/

Comment by HBH

- The Hunt for Kimathi

The Hunt for Kimathi (1958) by I Henderson & P Goodhart is a very interesting book.

- Capt JH du Plessis

I also know that Capt JH du Plessis from the SA Police visited Kenya and conducted an investigation into the origins and motivations of the Mau Mau uprising, and submitted a report to the South African Commissioner of Police. While the full contents of his report currently remains elusive in archives, its existence implies that South Africa was not merely lending personnel but was actively studying insurgency dynamics — likely to inform its own internal security strategies.

(I also know that officers of the police in the Belgian Congo visited the then Police Head Office.)

This aligns with the broader pattern of colonial knowledge exchange, where lessons from one theatre of unrest were adapted to others. If du Plessis for example examined the land grievances, ethnic tensions, and anti-colonial sentiments that fueled the Mau Mau, it’s plausible that his findings influenced our South African counterinsurgency doctrine.

It would be worthwhile to trace whether his report influenced SAP training manuals or Special Branch methodologies in the 1960s.

- If you have access to archival material or personal correspondence referencing his findings, it could be a rich vein for a future Nongqai feature.

- Van Zyl and Heine

More information on these two police officers are required.

Very interesting. I used to work with a former SA navy NCO (He served at the end of WW2) who had moved to Kenya after his time in the navy and served in the Kenyan Police. He had some interesting stories about the Mau-Mau rebellion and the police’s role.

Where any South African Police personnel involved in COIN operations during the Malayan insurgency? I have read that Rhodesian forces learned a lot of their initial operational methods there and I know that some South African troops are supposed to have served there.

Good day Marthinus – no, not that I am aware of. Any info on this matter will be appreciated. There were two dog masters, two from SAP Special Brach and Capt JH du Plessis that dis research in Kenya. Thank you for your enquiry.

That is interesting too. Who was the policeman please – and any idea of what he did in Kenya etc?

Dear Dave – In the city of Welkom where I as stationed during 1990 – 1991 I met a dog handler who worked on the Gold Mines. He came from Kenya and told me when I visit Kenya I must visit the Police Resort in Malindi – I have forgotten his surname … will make enquiries …. Greetings HBH