Duty, Politics, and Retrospection: A Reflection on Security and Accountability. Policing and Politics — A Thin Line

DUTY, POLITICS, AND RETROSPECTION: A REFLECTION ON SECURITY AND ACCOUNTABILITY: POLICING AND POLITICS — A THIN LINE

Brig Hennie Heymans

Abstract

This article explores the fraught intersection of policing and politics in South African history, tracing a cycle of duty, disloyalty, and moral reckoning from World War II through the democratic transition of the 1990s. It highlights the roles of key Security Branch officers under the Smuts government, including covert operatives like Captain Jan Taillard, and reflects on the ideological tensions that shaped their careers. Through the lens of Major GE Diedericks’ internment of BJ Vorster and the later abandonment of the South African Police during CODESA negotiations, the narrative examines how political shifts repeatedly left loyal officers vulnerable. The article argues for a retrospective moral accounting of the policeman’s role, invoking the Nuremberg Principles and emphasizing the need to honour integrity amid political storms. It concludes with reflections on South Africa’s intelligence community and the enduring lessons of service, sacrifice, and historical memory.

Keywords

- South African Police (SAP)

- Security Branch

- World War II

- Jan Smuts

- BJ Vorster

- GE Diedericks

- RS Leibbrandt

- Intelligence and Counterintelligence

- CODESA negotiations

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC)

- Kobie Coetzee

- LD Barnard

- National Party (NP)

- ANC transition

- Nuremberg Principles

- Operation Daisy

- Gerard Ludi

- Craig Williamson

- Political policing

- Historical accountability

- Nongqai tributes

In Dutch, only a single letter — “k” — separates ‘politie’ (police) from ‘politiek’ (politics). Yet in practice, these two domains often lie uncomfortably close. In South African history, especially during times of war and transition, the boundaries between policing and politics have blurred, sometimes dangerously so.

The Security Branch and World War II

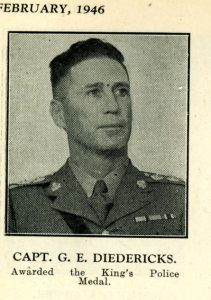

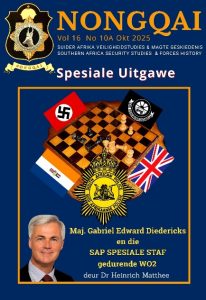

During and before the Second World War, several police officers served in the Security Branch under the Smuts government. Among them were Colonel JJ “Bull” Coetzee, Major GE Diedericks, General DA Bester and Major George Cloete Visser. One of the most notable figures was Captain Jan Taillard, a covert agent who infiltrated the Nazi Party in South West Africa. His intelligence work led to the arrest of RS Leibbrandt; a Nazi sympathizer and former boxer recruited by the Abwehr to assassinate General Jan Smuts and launch a coup. Taillard’s success helped shift the local tide in favour of the Allies.

Captain Jan Taillard

Some of these officers remained in service after the Malan government came to power in 1948 and rose to senior ranks. Others were deliberately sidelined. The Second World War was not merely a military conflict — it was a deeply emotional and ideological affair, and the police force itself was divided. Yet the work had to continue.

Major GE Diedericks and the Internment of BJ Vorster

Major GE Diedericks, MVO, KPM, serves as a poignant example. During the Smuts era, he was tasked with interning Advocate BJ Vorster — a fellow Afrikaner and future Prime Minister — under wartime emergency regulations. It was likely a painful assignment, a silent struggle between duty and conscience. Diedericks acted strictly within the law, serving the government of the day — a government navigating a world rife with ideological tension.

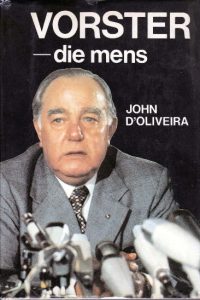

See pp 143 – 144

History would later turn with irony: BJ Vorster, once interned as a suspected enemy of the state, became South Africa’s Prime Minister from 1966 to 1978. According to accounts, Vorster remained formally courteous to Diedericks at official events but never pursued personal interaction — a subtle yet telling gesture of political and human distance.

Amnesty and the Transition to Democracy

During the critical negotiations between the National Party government and the African National Congress (ANC) in the early 1990s — notably at CODESA — the ANC initially proposed a blanket amnesty for politically motivated crimes on both sides. The aim was to ensure a peaceful transition and avoid cycles of revenge.

Justice Minister Kobie Coetzee, a key government negotiator, rejected the proposal, fearing it would project political weakness and undermine the National Party’s position. This decision was later viewed as a strategic misstep.

As negotiations progressed and the ANC gained leverage, they refused to return to the original amnesty proposal. Instead, they insisted on a more limited process — the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) — which required full disclosure for amnesty. This shift led Dr. LD Barnard, former head of National Intelligence, to openly criticize Coetzee, arguing that the refusal had left the South African Police and other security forces exposed and vulnerable.

The Circle Completes

With the arrival of 1994/5, the National Party’s influence waned and the ANC alliance assumed power. History, once again, completed its cycle. Many former members of the South African Police — men who had acted in the name of the state against the SACP-ANC alliance — were cast aside. They were rejected, declared obsolete, or even prosecuted. Some were openly hated and scorned.

History, it seems, is rarely kind to those who carry out duty.

The policeman’s role has always been unenviable: caught between duty and conscience, between loyalty and humanity. He does not serve a party, but the government of the day — yet he is often judged by the political winds of his time.

One can already foresee that, should a new party come to power in the next year or two, serving members of the SAPS may once again face bitter reckoning. The cycle of blame and accountability repeats itself in ever-changing forms.

Between 1966 and 1994, members of the former South African Police served during an exceptionally complex and violent era. Choosing a career in the SAP, SADF, or Secretariat of the State Security Council (SSSC) was not merely a profession — it was a life choice, fraught with personal and moral risk.

It is fair to ask whether the National Security Management System (NSMS), the SSSC, and the politicians of the time ever truly sat down with the Nuremberg Principles in mind and asked: Was the role of the policeman and soldier fairly accounted for — or merely functionally exploited and then forgotten?

Retrospective Wisdom

With the benefit of hindsight, it seems wise for any member of the security forces to limit themselves to classical policing — the protection of life, property, and public order — and to avoid the grey zones of intelligence, counterinsurgency, and riot control.

BUT — the reality is that the policeman swears an oath to serve wherever the country needs him. He does not always choose his terrain of duty; sometimes he is placed where the storms rage fiercest.

Nongqai has already published detailed tributes to Colonel “Bull” Coetzee, Major General HJ du Plooy, and Major GE Diedericks. Together, these three biographies form a trilogy of Special Branch commanders who served under the Smuts government during World War II. They offer a unique portrait of a time when loyalty, duty, and conscience collided — and when the policeman, more than any other official, bore the moral weight of the state.

Major Diedericks and his colleagues remind us that duty without understanding can easily lead to injustice — but that no society can survive without men and women of integrity and commitment. History may judge them, but it remains our responsibility to remember and honour their legacy.

What strikes me most is the completed circle: first, the NP government distanced itself from the seasoned political detectives of the Smuts era, and later — during negotiations with the ANC alliance — they abandoned the SAP once again. The cycle of disloyalty from NP politicians thus came full circle. Ironically, it was we who helped create the conditions for successful negotiation between the NP and ANC.

Final Reflection: Intelligence and Service

Our great post-war spies were Gerard Ludi (Q018) and Craig M Williamson, SOE, (RS 167). These men played pivotal roles in the state’s intelligence network. Williamson’s “Operation Daisy” involved international infiltration and counterpropaganda, while Ludi is regarded as one of the first Republican Intelligence operatives.

The spies of the 1961–1994 period were individuals any government could be proud of: honest, credible, and principled. Members of the security forces and intelligence community were, by and large, outstanding people — men and women who risked everything for their country and its people, serving the government of the day with unwavering dedication.

But gradually, we learn lessons from history — and circles are completed.

Bibliography

1. Kleynhans, Evert. Hitler’s South African Spies. Times of Israel interview.

2. D’Oliveira, John. Vorster – die mens. Perskor, pp. 143–144.

3. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa. Final Report, Volume 1, Chapter 5.

4. Williamson, Craig. Operation Daisy. Nongqai archives.

5. Wikipedia contributors. Craig Williamson. Wikipedia.

6. Nongqai. Gerard Ludi and Republican Intelligence. Nongqai.org.

Die volgende video is onder my aandag gebring. Dis lank maar kyk na einde oor SAP…..

https://sabctrc.saha.org.za/tvseries/episode70/section1/movie.htm