Colonel George Parson CBE, DSO and BAR

COLONEL GEORGE PARSON CBE, DSO AND BAR

Gerry van Tonder

Commanding Officer of the Southern Rhodesia Defence Force from 1929 to 1936, as an officer in the British South Africa Police (BSAP) Colonel George Parson served with distinction in the East Africa Campaign of World War One.

George Parson was born on 8 October 1879 in Cape Town, where his father was a well-known doctor and surgeon, and was educated at Rugby, England. He was commissioned into the Royal Garrison Artillery in January 1900, but he resigned his commission on 19 August 1903 and emigrated to Rhodesia, first entering the Civil Service, during which time he served in the Southern Rhodesia Volunteers and was appointed a Justice of the Peace. He then served with the Southern Rhodesia Constabulary (SRC) from August 1906 to February 1929 and rose to be a sub-inspector. The SRC was subsequently amalgamated with the BSAP, in which Parson was commissioned.

(Thanks Jason Lane)

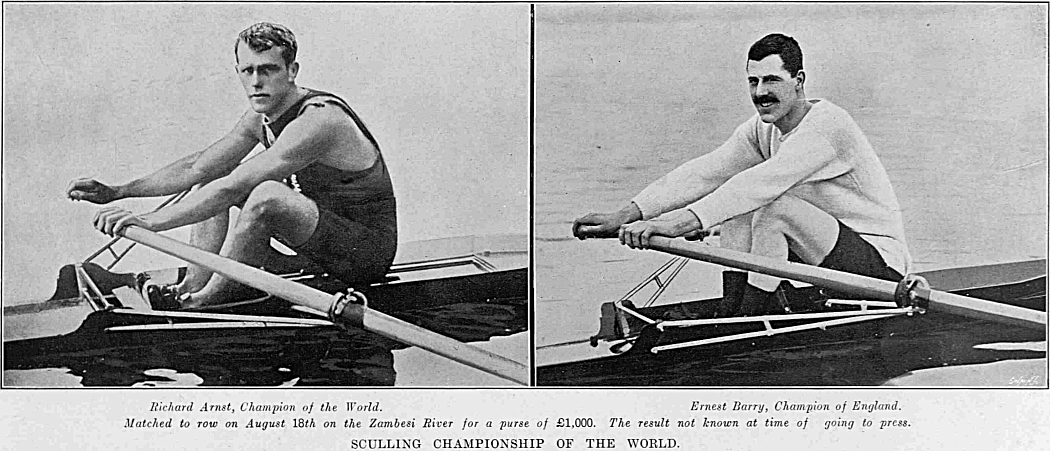

On 14 March 1910, the Bulawayo Chronicle reported that, “Sub-Inspector G. Parson, B.S.A.P., had to that date raised over £90 towards the expenses of a Southern Rhodesian crew to participate in the forthcoming Zambesi Regatta. Many other subscriptions were promised.” In January 1910 it was announced that the World Professional Sculling Championship would be held on the Zambezi River. The English sculling champion Ernest Barry, and challenger for the international title, had invited the world champion, New Zealander Richard Anst, to travel to England for the race, but he was unable to raise sufficient funds for the trip.

The British South Africa Company then offered to stage the match on the Zambezi, offering a £1,000 prize to the winner, and presumably covering each athletes travel expenses. They believed the race would promote the company and the region. Stakes and expenses were guaranteed by the company and the match was arranged to be run over a 7km course on the Zambezi River on 18 August 1910. The heat and the altitude affected both scullers but Arnst was the better of the two and he crossed the line in front of Barry to retain his title.

On 14 September 1910, Parson (29) married Amy Madalene Clare Fynn (25) in Uitenhage, South Africa. The marriage certificate shows he was an army officer residing in Bulawayo.

(Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 20 August 1910)

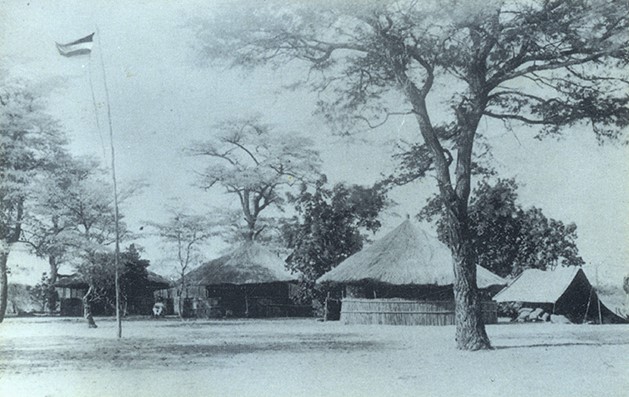

On 10 August 1914, Lieutenant Parson, in command of the 80-strong No. 4 Mobile Troop (Bulawayo), BSAP, was deployed to Victoria Falls to assist in securing the contiguous Caprivi Zipfel of German South West Africa. In command of BSAP forces at the Falls was Major Algernon Capell, future commanding officer of 2 Rhodesia Regiment during the East Africa campaign. But after only two days, Bulawayo ordered Parson’s troop to return as it had been decided that No. 1 Mobile Troop was strong enough to capture the German town of Schuckmannsburg (photo below) in the Caprivi. The village, in fact, fell without any resistance from the Germans.

(Rainer Buchmann)

Meanwhile, to the northeast the small forces of Northern Rhodesia, another BSACo-administered territory, had since September 1914 been fighting defiantly, with the assistance of Belgian Congolese troops, against German aggression. By August 1915 the Northern Rhodesia border with German East Africa (now Tanzania), known to the British living south of it as the Northern Border, urgently needed reinforcing due to the impending withdrawal of the Belgian troops.

On 12 August, the High Commissioner endorsed the principle of deploying two BSAP infantry companies to north-eastern Northern Rhodesia. Within a week, 137 permanent members of the BSAP had volunteered for enlistment in these companies. However, concerned that such an offtake would weaken the force’s civic policing responsibilities, the BSAP restricted the number of volunteers to two per troop.

Each company was to have an establishment of 125 men, and be a self-sufficient unit, including artillery and medical staff. Both companies would include a small number of BSAP, the other recruits being reservists who transferred from the Southern Rhodesia Volunteers, some men from 1 Rhodesia Regiment with recent service in German South West Africa and men recruited from the civilian population. The recruits were enlisted under the Police Ordinance for the duration of hostilities, and the two units were titled A and B Special Reserve Companies, British South Africa Police.

As the companies were needed on the northern border as soon as possible, training consisted of drill and a shooting test. The men received five shillings pay per day, five times more than the pay of recruits in the British Army. Uniforms comprised khaki shorts and jacket, with a BSAP shoulder flash in blue cotton the only insignia. Mounted infantry-pattern boots and dark brown puttees protected feet and lower legs. Kit provided included cavalry water bottles and cloaks, mess tins, haversacks and two bandoliers, one of which could be worn as a belt. Later all men received British 1908–pattern webbing equipment with ammunition pouches. Various patterns of sun helmet were issued. The rifle was the standard BSAP issue, the SMLE (Short Magazine Lee Enfield) No. 1, Mark III, with an 18-inch bayonet.

A Company, commanded by Jameson Raid veteran Major J.S. Ingham, BSAP, left Salisbury by train for Victoria Falls on 17 August 1915. The force was made up of two officers, a sergeant-major and 142 other ranks. At Bulawayo, Major Ronald Murray, BSAP, met the train in Bulawayo, yet unaware that in the near future he would command both companies; a force titled the Southern Rhodesia Column, but more commonly referred to as “Murray’s Column.”

On arrival at Victoria Falls, A Company crossed the Zambezi River to Livingstone in Northern Rhodesia, where they set up a tent camp at Regatta Siding. At this point, lieutenants Francis Stephens and George Parson joined with 21 other ranks.

Regatta Siding, Zambezi River, Livingstone, Northern Rhodesia, 1910.

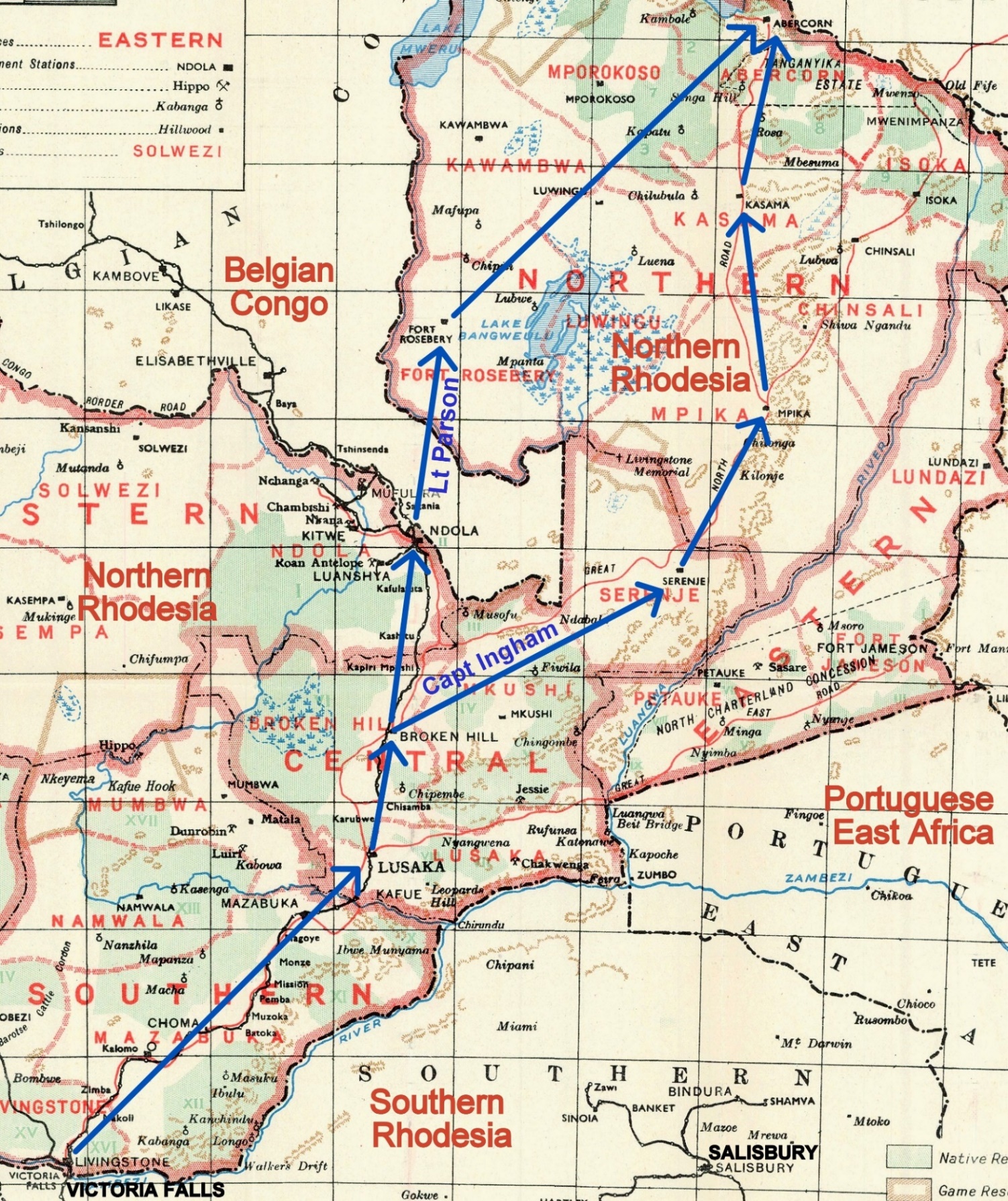

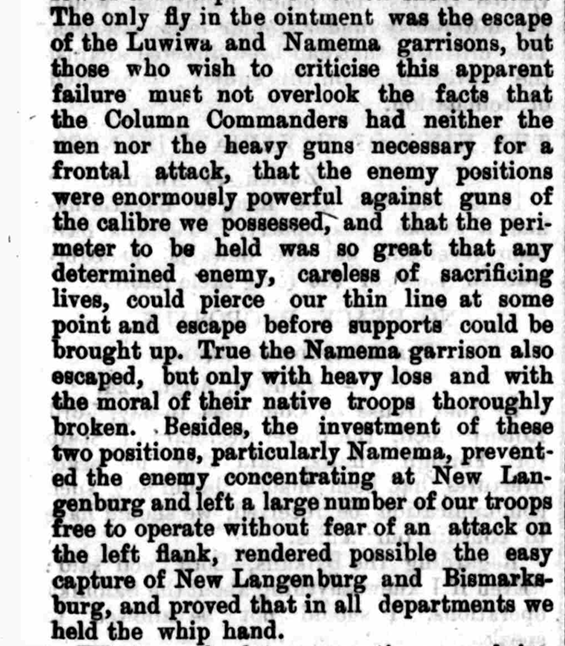

Now with a strength of 165, the company was split into two halves; Parson and Stephen each commanding a half-company. They travelled together by train to Broken Hill, where Ingham and his men detrained and set off on foot for the arduous march to Abercorn on the border with German East Africa (see map above).

Parson and his half-company continued on with the train to Ndola on the Belgian Congo border. From there they marched cross-country, passing through Fort Rosebery to the west of Lake Bangweulu, and then in a north-easterly direction to Abercorn. Parson arrived at Abercorn on 4 October, a day after Ingham’s arrival and six weeks after leaving Livingstone.

On arrival at Abercorn, the two exhausted half-company men were massively disappointed with the conditions there. It was the rainy season, but whilst there were barbed-wire and trench defences, there was no accommodation. In the absence of local labour, the men had to set aside their military duties to build mud huts. Accustomed to African ‘servants’ performing such manual-labour tasks, many grumbled at having to clear a large area of grass and trees for a parade ground.

Adding to their woes was the poor quality and selection of food. On the few occasions that meat was available, it was flyblown. For lunch one day, beef in such a state was served, resulting in the men objecting by having one man from each section standing up with his plate of ‘food’ in his hand, refusing to eat the meat in protest. Ingham and Surgeon-Captain Kinghorn immediately addressed the situation. Bully beef rations were increased to one and a third tins a day, and a whole tin of jam instead of only half a tin. The most popular improvement was whisky, at the rate of a bottle per 12 men instead of 15. Slaughter cattle would be sourced and brick ovens constructed. A BSAP 12.5-pounder quick-firing Maxim-Nordenfelt field gun and detachment joined ‘A’ Company later, while a 7-pounder muzzle-loading mountain gun, named ‘May Jackson’ after a Salisbury barmaid, moved to Abercorn after seeing action during an enemy siege of the post at Saisi.

“May Jackson”, the 2.5-inch Armstrong Mountain Gun on display in the Police and Army Museum, Lusaka, Zambia, in the early 1960s. The whereabouts of this gun is now unknown.

(AngloBoerWar.com)

B Company, commanded by erstwhile Bulawayo mayor (1904-06), Major Walter Baxendale Southern Rhodesia Volunteers (KIA 23 October 1916), took a completely different and less arduous route. They travelled by train to the Indian Ocean port of Beira in Portuguese East Africa (now Mozambique), and then travelled by ship, river steamer, rail, road and lake steamer up to Karonga near the head of Lake Nyasa. From there they marched to Fife on the Northern Rhodesian border, arriving there on 18 October. Major Murray accompanied the unit. At Abercorn, A Company settled into a regular routine of long marches, musketry and drill, but disappointment grew at the absence of any Germans with whom to do battle.

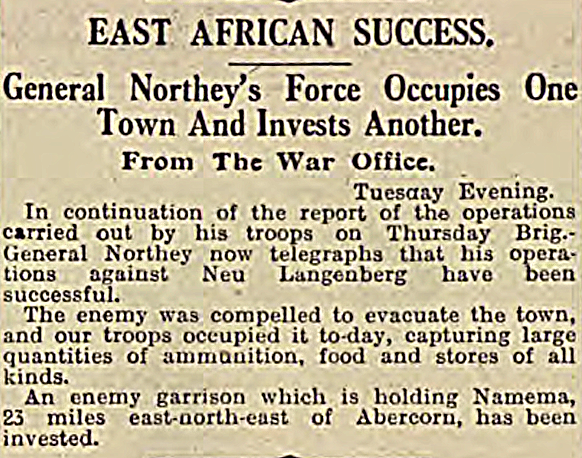

In November 1915, former 1st King’s Royal Rifle Corps commander, Brigadier-General Edward Northey, was appointed to command all forces on the Nyasaland/Northern Rhodesia border. Northey, his command titled Norforce, drew up plans for his advance into German territory. His force strength included elements of the 1st and 2nd South African Rifles, Nyasaland King’s African Rifles, Northern Rhodesia Police (NRP) and the BSAP.

On 18 February 1916, Murray was given command of the Rhodesian Northern Border forces and promoted to lieutenant-colonel. In April, together with four companies of the NRP, B Company, BSAP, was moved from Fife to join A Company at Abercorn. This meant Murray now had all Abercorn forces under his immediate command: the two BSAP Service Companies and those of the NRP. Officially, it was titled the Southern Rhodesia Column, generally referred to as “Murray’s Column.”

Rhodesian column on the march. (IWM)

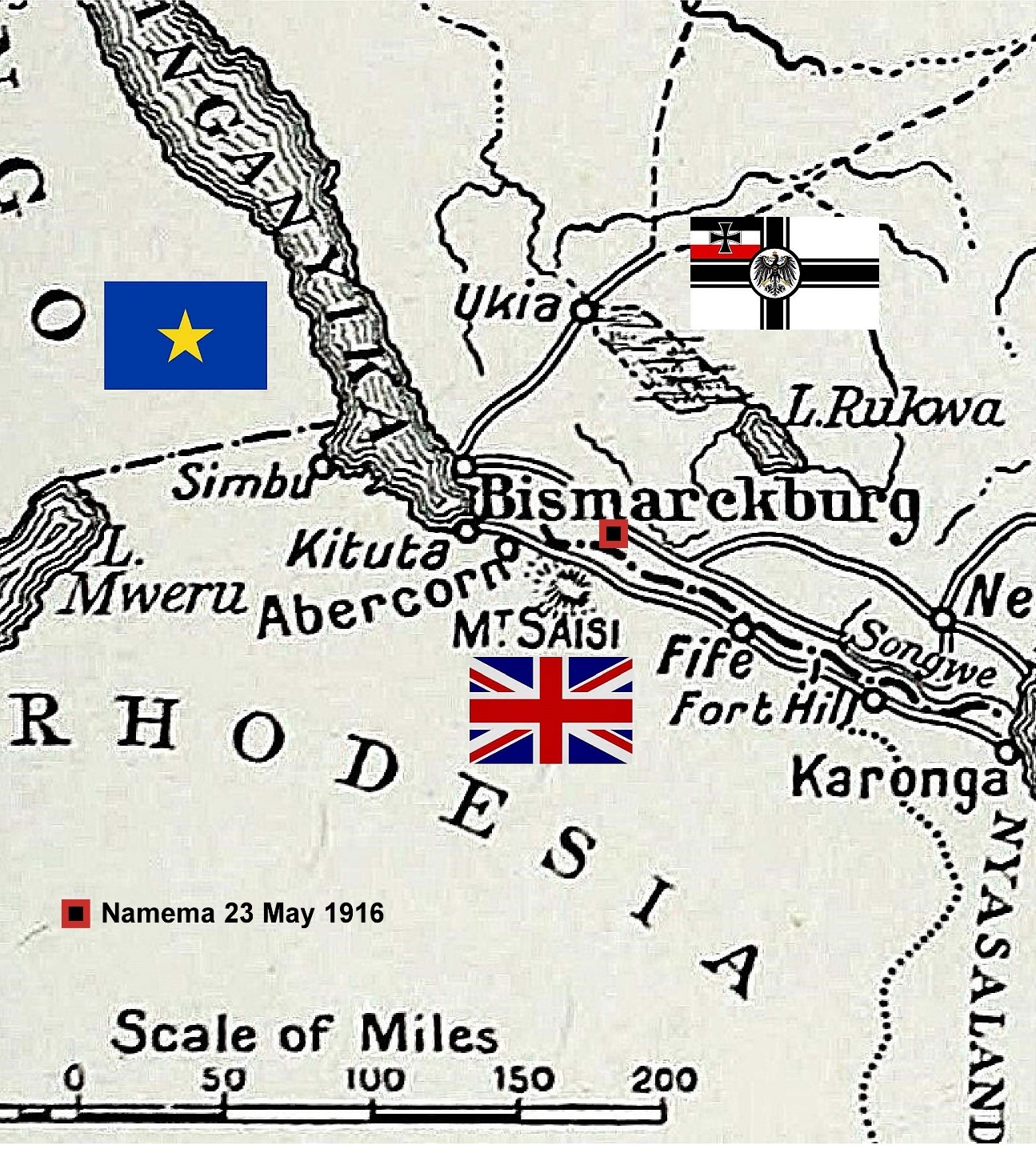

In the last week of May 1916 Northey had four columns poised to attack different enemy fortified locations just across the border in German East Africa: Ipiana, Mwembe and Namema. Murray’s Column was the westernmost one and was tasked with attacking the German position at Namema, 26 miles northeast of Abercorn. The stronghold consisted of two forts, 35 yards apart, on commanding ground. Murray’s first task was to be an attack on the German post at Namema.

The position was manned by the German 29th Field Company with an estimated strength of 200 Schutztruppe (colonial troops) and 30 white officers and non-commissioned officers. Well-constructed underground stores ensured that British artillery fire could not destroy ammunition, food and water stocks. Murray divided his column into four sub-units:

A Force under Captain C.H. Fair, NRP: ‘A’ Company NRP, half of ‘A’ Company BSAP, with 2 machine guns.

B Force under Captain G. Parson, BSAP: ‘D’ Company NRP, half of ‘A’ Company BSAP, with 2 machine guns.

C Force under Captain H.C. Ingles, NRP: ‘C’ Company NRP, half ‘B’ Company BSAP, with 2 machine guns.

Reserve under Captain F.S. James, NRP: half ‘B’ Company NRP, a section of ‘B’ Company BSAP, with 2 machine guns, the 12-pounder BSAP artillery gun and a section of two 75mm mountain guns manned by the 5th Battery, South African Mounted Rifles.

(The Times History of the War/Gerry van Tonder)

When Murray organised his column for the advance on Namema (map above), the 7-pounder Armstrong mountain screw gun ‘May Jackson’, mentioned earlier, was to be left at Abercorn. However Captain Langham later claimed to have seen ‘May Jackson’ in action at Namema. The gun may well have been brought up between 23 May and 2 June 1916.

Seven-pounders (perhaps the pre-1880 pattern) came to Rhodesia with the Pioneer Column in 1890 and remained in the British South Africa Company’s armoury, seeing action in the Matabele War in 1893. Two of these, together with a 12.5-pounder were lost in the Jameson Raid. They were recovered by British troops at Rustenburg on 14 June 1900 and four days later at Klip Kop. According to War Office records both guns were, “Handed over to the B.S.A.P.” Up until the 1960s ‘May Jackson’ was on display in the Police and Army Museum, Lusaka, Zambia.

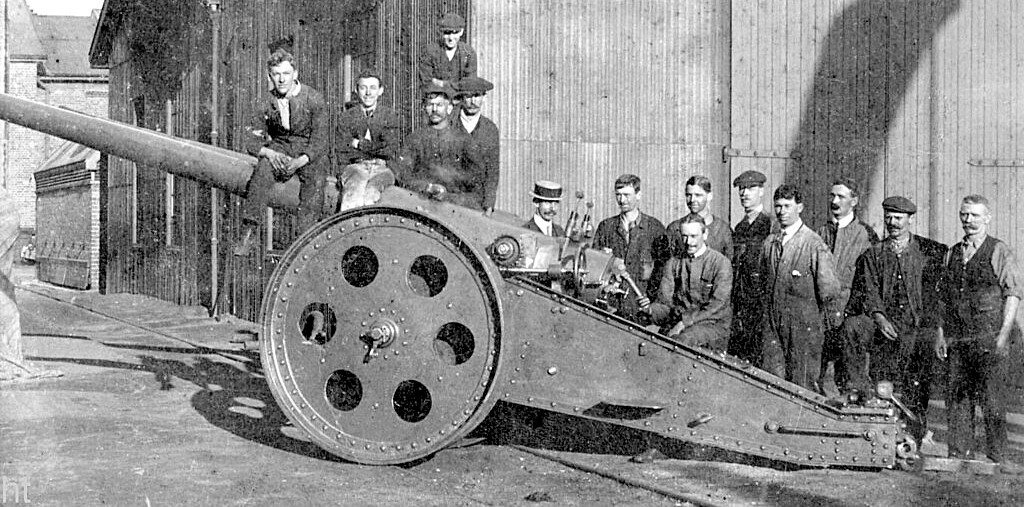

Notwithstanding the uncertainty about ‘May Jackson’ being deployed against Namema, only a 12-pounder and two 75mm mountain guns were to accompany the Reserve Force. The 12-pounder was a British naval gun fitted to a bespoke field carriages in the Salt River railway workshops, Cape Town (photo below).

(HiltonT)

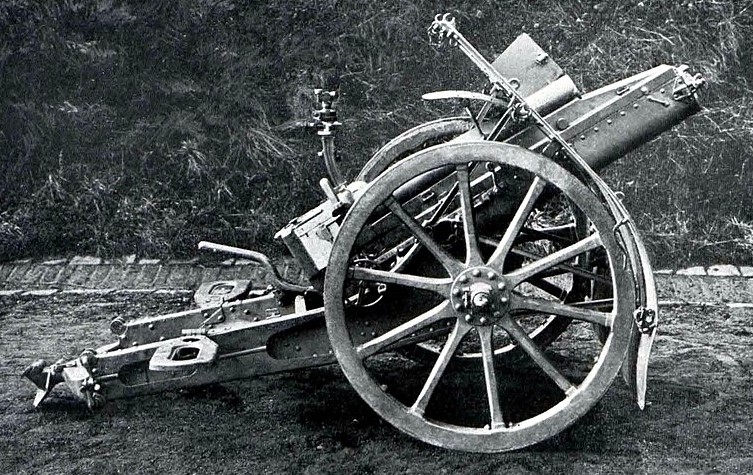

The 75mm guns were newly arrived modern Krupp Gebirgskanone-13, breech-loading howitzers (photo below) captured in German South West Africa and manned by 5th Battery, South African Mounted Rifles.

(Krupp Arms Company)

The column departed from Abercorn at 2.00 p.m. on 23 May 1916. The Lumi River, which acted as the border, was crossed by portable boats and an advanced base camp was established six miles west of Namema. A section of the reserve manned the base camp with a machine gun. At 2.00 p.m. on the next day ‘A’ and ‘C’ Forces marched out to the southwest, followed an hour later Parson and ‘B’ Force, heading through the Liambi Hills to the northeast.

When Namema came in sight Murray realised that it was too strong to attack, so he dispositioned his three force commanders to surround and besiege the enemy. The guns, under Captain Chalmers, were placed on high ground to the northwest, while the infantry moved to within 200 yards of the forts, from where they sniped at the defenders. Parson, with three sections of A Company, BSAP and C Company of the NRP, closed in from the north.

Just before first light on the 28th, German fort commander Leutnant von Francken led a group of schutztruppe out on a counterattack. In the ensuing clash four BSAP men were killed: Corporal Francis Hoal was shot in the head when he challenged the Germans; Private John Short shot in the neck; Private H.J. Kemp shot in the face; Private Hugh Malcolm Steele shot by a sniper.

Lieutenant John Hendrie, BSAP, had a one-on-one shoot-out with Franken during which a bullet fired by Hendrie raked the German officer’s skull. He was taken prisoner and hospitalised, but he died two days later.

(Daily Sketch 31 May 1916)

The siege finally ended on 4 June when the Germans hoisted a white flag over the fort. Frustratingly for Murray, the Germans had evacuated the post, leaving only a few of their wounded behind. After sending his artillery pieces back to Abercorn, Murray set off in pursuit at a brisk pace. At Mwazi Mission, finding the fleeing Germans had already moved on, Murray decided to turn his attentions on the German town of Bismarckburg to the west. Situated at the southern tip of Lake Tanganyika, the German stronghold was a brutal 40 miles away. Increasing numbers of his men had developed badly blistered and swollen feet and had to continue at a much slower pace. After a bout of fruitless exchanges of words and rifle fire between the two rivals at Bismarckburg, on the night of 8/9 June the Germans vacated the post by boat.

(Daily Malta Chronicle and Garrison Gazette 30 August 1916)

Over the next few weeks, Parson endured severe hardships as Murray led his column east to Neu Langenburg, and from there north-eastwards towards Iringa where, it had been reported, a 700-strong German force held the road to Kilossa. However, the enemy remained elusive, and on 28 August Murray’s companies, formed into columns of four, marched into Iringa unchallenged. Murray immediately set off after them, encountering stiff resistance from a strong German rearguard.

Eventually, in the last week of October, the two sides clashed at Mkapira, south of Iringa, on the Ruhudje River. Arriving at this settlement, Murray joined up with Major George Hawthorn who was in command of three companies of the 1st King’s African Rifles. The combined force set about strengthening defences and apportioning positions. Parson’s B Company and A Company, BSAP, faced south and southeast, a KAR company the southwest, the NRP the west, and the rest of the KAR the north and northeast.

Von Lettow-Vorbeck’s map of his troop movements to the southeast from May 1916.

The author has marked the sites where Murray’s Column had moved to confront the enemy.

(Annotations Gerry van Tonder)

In what became known as the Battle of Iringa, on 22 October 1916 Oberstleutnant Georg Kraut and around 2,000 men of the Southwestern Group commenced hostilities by firing 60mm gun shells into the British encampment. Fortuitously, a ration convoy had reached Mkapira the day before which, together with stocks of dried elephant meat, ensured the camp was well-provisioned.

An artillery duel followed, with Kraut believing he could starve the British into capitulating. When the guns fell silent at night, Rhodesian scouting parties ventured out to plot the German positions. With this intelligence to hand, Hawthorne chose 5.30 a.m. on the morning of 30 October to break out and take the fight to the enemy. The Rhodesians attacked across the open ground while the KAR broke out through the swamp to the north and east that Kraut believed was impassable.

Facing the German 10th Field Company, Murray drew up two sections to bayonet charge the German trenches. By 8.30 a.m. the ground hitherto occupied by the Germans had been cleared, leaving 35 dead and 82 taken prisoner.

The BSAP lost four men killed: Private Arthur Leonard Bradbury, Private James Curran, Private Felix Joseph Hampson and Private Jack William Judson.

They are buried in the CWGC cemetery at Iringa, Tanzania. (Photo: Capt. C Ross – SA Navy Ret – via CWGC.)

A company of schutztruppe on parade, German East Africa, 1916.

(Bundesarchiv)

On 1 November, Parson moved his B Company to Kasinga, seven miles off, where he was joined by A Company. Throughout the month Parson continued to be engaged in fights with the retreating Germans. Despite constant pressure from the enemy, Murray’s BSAP companies were able to repeatedly repel German attacks on the Lupembe garrison.

For the BSAP and Rhodesia Native Regiment (RNR), the capture of the German garrison at Ilembula at the end of November was a highlight of the campaign. Commanded by Leutnant Huebener, the German stronghold comprised 290 white and black soldiers, a 4.1-inch howitzer originally from the German battleship, Königsberg, three Maxim machine guns and substantial stocks of food and ammunition.

Christmas 1916 found the BSAP force at Lupembe, but there was no respite in Northey’s pursuit of Major Kraut south of the camp. Finding Kraut at Msalala, Colonel Hawthorn, NRP, commander of this sector of the Nyasa-Rhodesia Field Force, instructed Murray’s BSAP companies to attack the enemy position from the south on New Year’s Day. But once more, in actions that continually frustrated the Allies in the whole campaign in German East Africa, on 6 January the Rhodesians were left to contend with the German rearguard as Kraut slipped away.

By the end of the month, Kraut had arrived at Gumbiro on his way to intersect the Wiedhaven–Songea road. Already at the position was Captain Max Wintgens, reportedly with a force of 500 men, 15 Maxims and 2 field pieces. The two German leaders decided to go their own way, and Wintgens marched west in the direction of Lake Rukwa. Murray and the RNR under Colonel Tomlinson were tasked to pursue Wintgens. However, upon reaching Ipale on 29 May, word was received that Wintgens had died of typhoid in a Belgian field hospital.

Porters with Captain Wintgen’s column approach Gumbiro.

(Bundesarchiv)

In January 1917, commander of Allied forces in East Africa, South African General Jan Smuts, left for London to assist the British War Cabinet in its prosecution of the war in Europe. Despite Smuts believing the war in East Africa was over, his replacement, Lieutenant-General A.H. Hoskins, KAR, did not share the former Boer War general’s optimism, and called for reinforcements and vast amounts of extra war matériel. London failed to understand Hoskins’s difficulties, and after only four months, he was replaced by another erstwhile Boer War general, Jacob ‘Jaap’ van Deventer.

In May, as the dry season began to grip, Murray was nearing Tabora in the far north, where he hoped his men could rest and recover in the largest town in German East Africa. But such a luxury remained as delusory as the very enemy they were trying to catch – they were ordered to march back south to Rungwe. They had relentlessly dogged Wintgens ever northwards, only to have to march away. One of his men said, “Every bone in my body aches from the continued marching and my feet I can hardly put to the ground they are so sore.” Regardless, Murray turned his men around for the 60-mile slog to Kitanda, for which he had been given three days to reach.

In June Murray was tasked with driving the Germans back to Mpepo, while the Belgians struck out from Iringa and the NRP along the west bank of the Ruhudje. At British-held Songea to the south, large stocks of supplies had been accumulated and an airstrip built. Quantities of the new Lewis machine gun (photo by Acabashi below) were received, and several members from the BSAP companies were promoted to NCOs as instructors in the weapon.

By this time, many of Murray’s white officers and NCOs were hospitalised in Songea, suffering from exhaustion and fever. Murray, however, believed these men should be back in the front line as soon as they have recovered sufficiently. In this, he was at odds with medical staff, who referred Murray to an order from Northey that column medical officers could recommend a maximum of three months convalescent leave. Responding in writing to a letter from Murray in which the BSAP commander objected to the number of his men on recuperative leave, Assistant Director of Medical Services, Major Kinghorn, wrote,

The point arises as to whether any useful purpose is served by keeping men up here [Songea] whom the Medical Officers consider unfit and who, as often has happened, go sick again within a very few days of their discharge from hospital.

It must be recognised that Europeans cannot remain indefinitely in the Tropics without impairment of their physical and mental health. . . The Rhodesian troops, since they arrived on the border, have had a much more strenuous time of it than any other troops in the field, and during this time they have been continuously exposed to all weathers, including two wet seasons, and while rations have been as good as could possibly be expected under conditions inseparable from active service, there has been a lack of fresh food, a deficiency which, in time, is bound to affect a man’s general health and his resistance to disease.

When one takes into consideration that the bulk of the Rhodesians were recruited from men following sedentary occupations and that they were sent up with practically no preliminary training, one can only wonder that they have not started giving in much sooner. . . Every Rhodesian Medical Officer is unanimous in the statement that the Europeans taken as a whole, are now gone in and should be relieved.

(Murray’s Column, Tony Tanser, BSAP Regt. Assoc, UK, 2009)

This inflamed Murray, who accused the doctor of “insubordination and discourtesy.”

At this time Northey placed Murray in command of the Songea area, with the prime objective of neutralising Oberleutnant Heinrich Naumann’s forces. At his disposal Murray had six NRP companies, averaging 125 each, remnants of the BSAP service companies and 1RNR under Lieutenant-Colonel Clive Lancaster Carbutt. Around mid-August, Murray’s forces started to close in on Naumann’s base at Mpepo. However, several attempts to take the German position in the last few days of August failed, and Naumann fled eastward.

Murray was besides himself at the slow progress and lack of results by Major Fair, commander of the NRP, demanding he “clear Aumann [sic] out of Mpepo, or destroy him. Your orders are to drive Aumann [sic] east, what have you done in this respect.” Soon thereafter Murray reported Fair to Northey, blaming him for allowing Naumann to get away, and requesting Fair be replaced by Major Stennett, NRP.

As the conflict in German East Africa drew to a close, the Commander-in-Chief of German forces, General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck crossed the Rovuma River into the relative safety of Portuguese East Africa (Mozambique). For Murray and the BSAP companies, there was small consolation when Generalmajor Theodor Tafel surrendered before he could join von Lettow-Vorbeck.

At his headquarters in Songea, Murray started to retrieve his forces who were spread far and wide. Parson’s B Company was on the Rovuma River, patrolling south from Tunduru in extremely hot and humid conditions. On 18 December 1917, Parson arrived back in Songea.

Wounds, sickness and leave had so decimated the BSAP service companies that they could no longer be classed as such. In Murray’s report to Northey on 21 January 1918, he wrote,

The B.S.A.P. Service Company no longer exists, all the men having been absorbed into the machine and Lewis guns and other department units. I have been informed officially that European casualties can no longer be replaced from Salisbury and, in this respect, I would point out that 55 men have been sent south during the past three months, for three months recuperative leave, and that there is little or no chance of them returning. Medical boards are held on them, and they are nearly always discharged being unfit for further service up here.

(Murray’s Column, Tony Tanser, BSAP Regt. Assoc, UK, 2009)

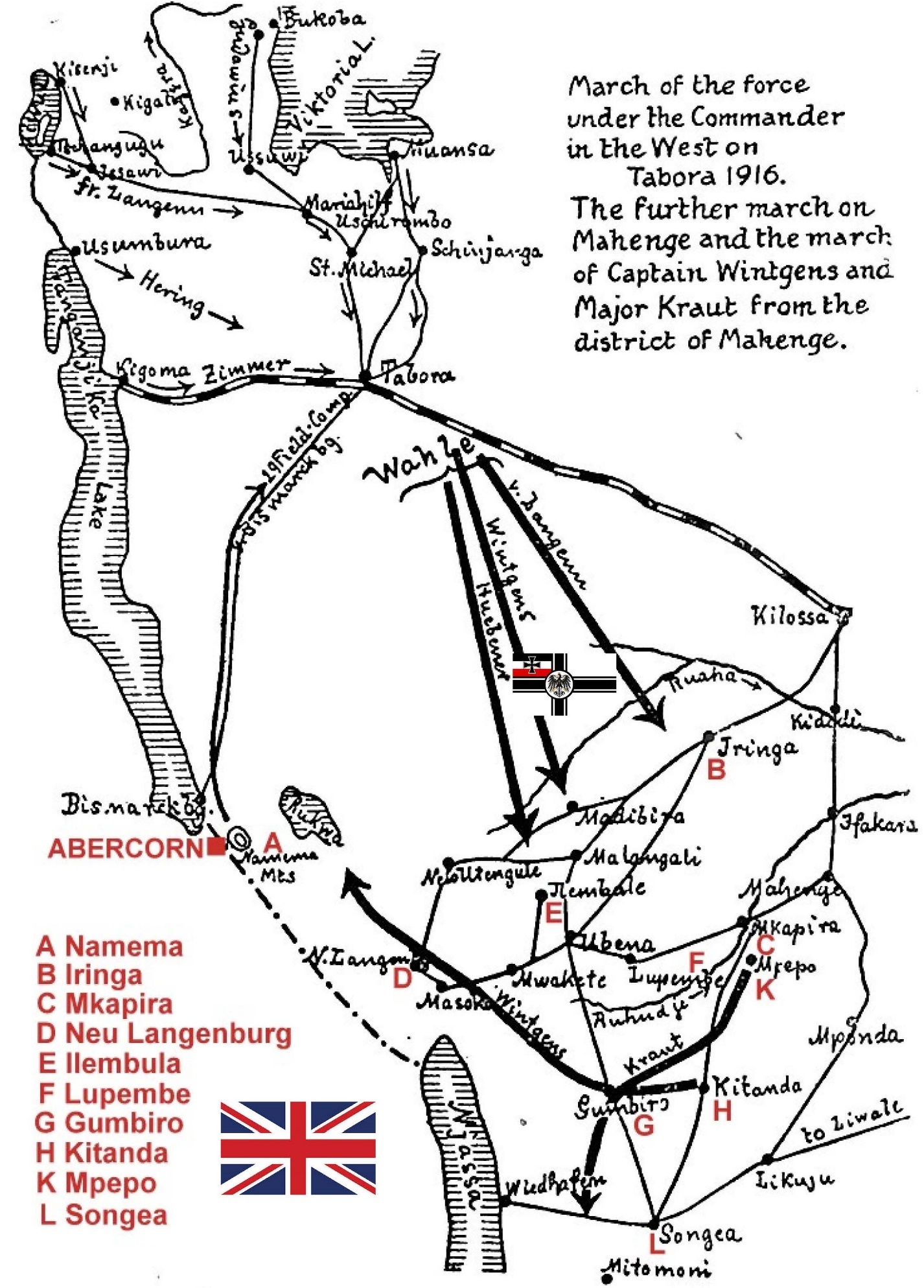

The tragic truth of the Rhodesians’ campaign: victory came at a great price.

On 29 June 1920, Murray himself paid the ultimate price, passing away in England of an aortic aneurism brought on from repeated bouts of malaria contracted during the East African Campaign. Von Lettow-Vorbeck was never captured, and only with the signing of the Armistice in Europe did he formally surrender at Abercorn.

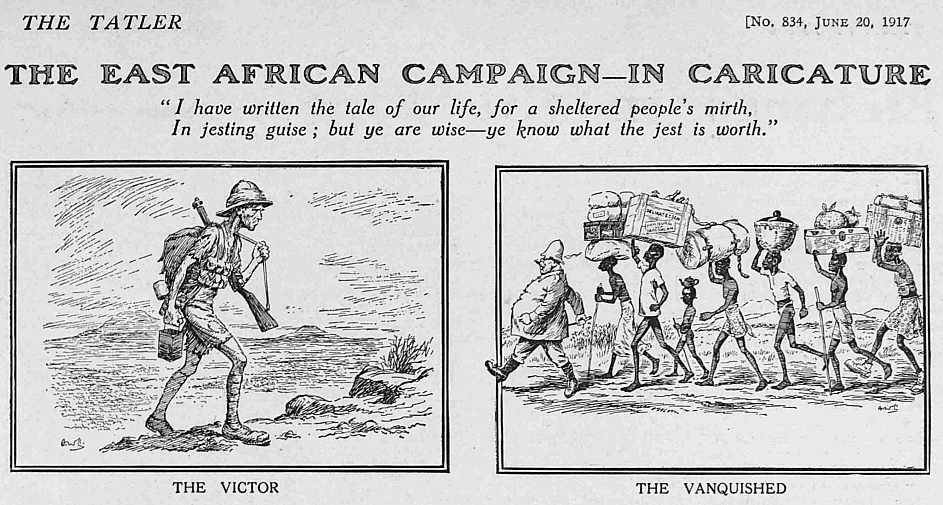

Parson survived the conflict and inhospitable climatic conditions, returning to Rhodesia with an outstanding record of distinguished service in a theatre of war. In The London Gazette of 4 June 1917, he was appointed a Companion of the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) for “distinguished service in the field”. The DSO was awarded a second time (Bar) in The London Gazette of 28 December 1917.

On no fewer that three occasions during the campaign Parson was Mentioned in Despatches, once by General Hoskins (The London Gazette 22 September 1917), and twice by General van Deventer (The London Gazette 13 March 1918 and 20 January 1919).

After the war, Parson returned to army staff duty, where he played a major role in the inauguration of the country’s territorial force, the Rhodesia Regiment. After serving as Chief Staff Officer, he was promoted to Commandant of the Southern Rhodesia Defence Force in April 1929, a position he held until 1936. He was promoted to the rank of colonel in 1930, and in 1934 he was appointed a Commander of the Military Division of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) (The London Gazette 4 June 1934).

Until 1929, attempts to develop an aviation industry in Southern Rhodesia had been undertaken mainly by private individuals and companies. In 1929, however, the government took the first step in regulating and actively participating in aviation by passing the Aviation Act (No. 555 of 1929), which came into force in April 1930. The government also created a Department of Civil Aviation within the Department of Defence, appointing Parson Director of Civil Aviation, a position he held for several years. In this role, he was instrumental in establishing a system of landing grounds throughout the country, which received high praise from visiting pilots.

Parson gained renown in his younger days, both in England and Africa, as a rower, and in later years he was a keen golfer. For ten years he was President of the Rhodesian Golf Union and captain of the Royal Salisbury Golf Club for a similar period. He was also a steward and the honorary starter of the Mashonaland Turf Club.

Parson died in Durban, Natal, South Africa, on 20 November 1950, aged 71.

Colonel George Parson’s honours and awards. (Noonans)

Top: Commander of the British Empire, Military Division (CBE) neck badge.

Group: Distinguished Service Order, with Second Award Bar; 1914-15 Star; War Medal;

Victory Medal with Mentioned in Despatches (x3) Oak Leaf device; Jubilee Medal (George V, 1935).